Housing costs are high because there are not enough homes. We must do everything in our power to add as many residences to the nation’s stockpile as quickly as possible. In the words of newly elected Prime Minister Mark Carney, the best solution to the housing crisis is to “build big, build bold and build now.”

Parliamentarians and policy wonks across the political spectrum have endorsed various homebuilding schemes designed to pave the way to affordability. Proposals on zoning deregulation, ‘missing middle’ housing, innovative construction techniques, and training programs designed to address gaps in the labour market all revolve around the conviction that more housing equals lower prices. After all, common sense says the core of this crisis is a basic supply and demand equation.

But is common sense right?

Will tearing down greenbelts to build expensive suburban developments really bring prices down? How many purpose-built rentals will real estate investment trusts have to develop before their AI tools decide to lower the rent? Will the construction of hundreds of thousands of affordable homes get the under-40s into homeownership when mom-and-pop landlords dominate the market? Is it true that more houses bring housing costs down?

When researchers think about these questions their first task is to work out how to measure supply and demand dynamics. One of the proxies they use is vacancy rates. If vacancy rates are high that means there are a lot of empty homes in a given region and we can assume that housing is relatively plentiful. If, on the other hand, vacancy rates are low that means that most of the buildings are full and housing may be becoming scarce. We can use vacancy rates to test our common sense. If supply and demand is in fact determinative of housing prices, then relative price changes should be similar in cities with comparable vacancy rates.

A 2025 CMHC report shows that Edmonton and Calgary have had similar vacancy rates for the last three years, but despite their comparable supply restrictions Calgary’s housing values rose by 17 percent while Edmonton’s rose by just five percent. Put another way, Calgary’s housing prices are rising three times faster than Edmonton’s—a difference that amounts to tens of thousands of dollars in the average homeowner’s property value. How can housing markets in similar cities be subject to virtually the same supply and demand pressures and have such divergent price fluctuations?

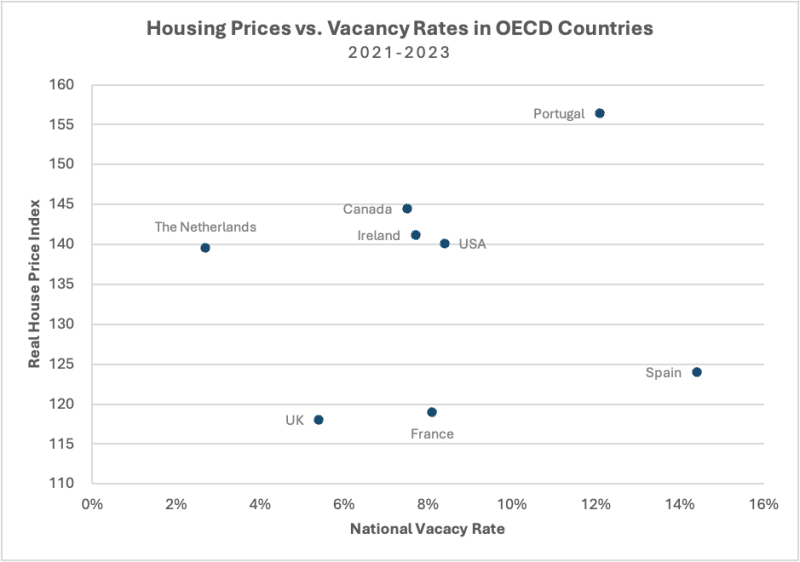

The credibility of supply and demand frameworks is further undermined when we look at international markets. Recently compiled datasets from the OECD on indexed housing prices and vacancy rates are especially telling. Some countries, like Portugal, have substantially more surplus housing than Canada but struggle with even higher housing costs. Other countries, like the Netherlands, have greater housing scarcity than we do, but have been able to keep their prices under Canadian averages. When the data is visualized there is no obvious correlation between relative housing abundance and average home prices.

(A note on these data sets: The ‘real house price index’ was created by the OECD to allow for apples-to-apples comparisons between international markets. Prices are corrected for differences in currency values, consumer purchasing power, and seasonal variation.)

A striking data point on this graph is France. France is facing similar supply and demand pressures as Canada, but French homes cost substantially less. These lower prices are a product of more than a decade of public policy designed to reshape France’s housing market around the needs of citizens. Since 2015 the national government has required local authorities to build affordable social housing, setting the expectation that 30 percent of total housing stock be non-market by 2030. The French government tracks these quotas carefully and imposes strict fines on municipalities that don’t keep up. As the data shows, this period of home building hasn’t done much for supply and demand pressures, but the fact that France’s housing investments are primarily a decommodification effort has led to significant improvements in affordability.

France demonstrates that it is the rate of housing commodification, not the relative supply of homes, that determines housing costs.

We see this same phenomenon play out at the city level.

In 2021 Vancouver had an extremely restricted housing market with just 495 dwellings for every 1,000 people. That year, the average price of a detached or semi-detached home was over $2 million. At the same time Vienna had an even tighter housing market with 448 dwellings per 1,000 people, yet the average price of a detached and semidetached home was only €720,000 (or $1,080,000). Even though Vienna faced greater supply constraints than Vancouver, home prices were 50 percent lower.

The primary driver of Vienna’s superior housing affordability is the fact that over 50 percent of Viennese homes are social or co-operative housing. Vienna was able to retain greater affordability in a heavily restricted market because of its cultural and political commitment to housing as an essential good and not a speculative investment.

It is clear that supply and demand curves are not sufficient for understanding the housing crisis. We can build all we want, but if we are building houses as financial assets and not as places for people to live prices are going to stay high. We saw this in the 2010s when huge booms in the construction of luxury condos in San Francisco and London resulted in lots of empty penthouses but did nothing to address affordability. The act of building matters a lot less than the decisions we make about what to build, who to build for, and most importantly, who will own our homes.

Institutional economists have recognized this fact. In 2022 Doug Porter, chief economist for the Bank of Montréal, noted that Canada’s supply of housing was not out of line with our nation’s peers on the global stage. Yet, he wrote,

somehow, our average home prices are (roughly) 60 percent higher on average than in the U.S., with essentially the same level of supply per capita. Yes, we should do all we can to encourage supply; but clearly there is more at work here than that.

Things have changed since Porter’s statement: American home prices have steadily risen and Canadian prices have climbed down off the cliff they found themselves on in mid-2022. However, it should be noted that the recent rise in American home prices is not correlated with any major shift in vacancy rates, but rather with an increasing investor presence in the American housing market.

Our politicians and our common sense tell us that housing prices follow simple supply and demand dynamics, but real-world evidence shows that speculation, financialization, and commodification can decouple prices from physical housing abundance. National and international case studies support the fact that in contemporary markets housing prices are determined first and foremost by the rate of commodification with relative quantities of housing being at best a secondary factor.

Ultimately, political injunctions to build more housing are insufficient. By monomaniacally fixating on increasing supply we lose sight of the complexity of the issue. Our attempts to restore affordability under the banner “build big, build bold and build now” (which has effectively been federal government policy since 2017) have only made things worse.

The housing crisis will not be resolved by increasing supply, but by increasing the right kind of supply. Constructing more homes will only lower costs if they come with long-term affordability covenants, are kept out of reach of investors, and are paired with significant non-market alternatives.

James Hardwick is a writer and community advocate. He has over ten years experience serving adults experiencing poverty and houselessness with various NGOs across the country.