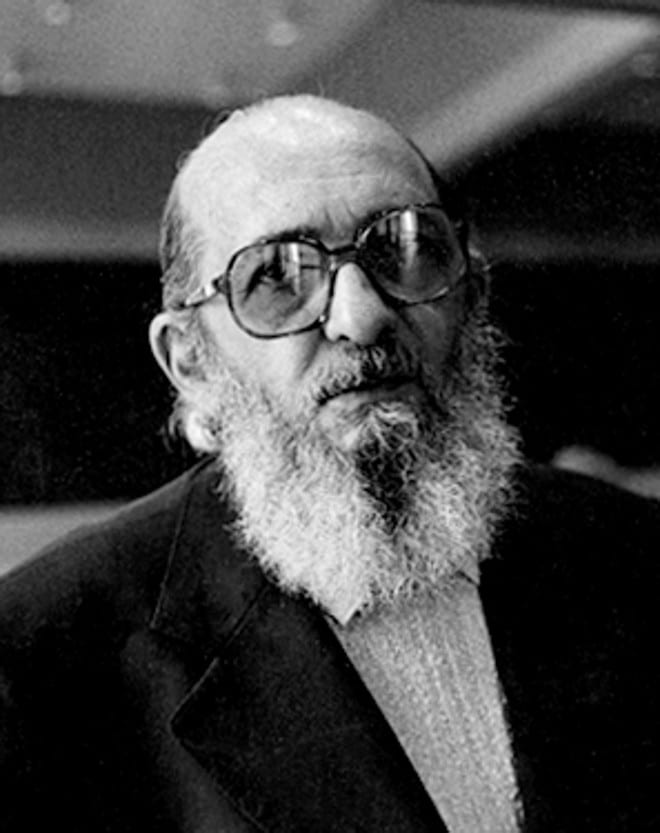

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, education has become a frontline in the ideological struggle over the future of global capitalism. The coordinated assault on teachers, curriculum, and institutions of public learning is not an isolated culture war but a structural feature of neoliberal governance. In this context, the pedagogical philosophy of Paulo Freire demands renewed attention—not as an abstract theory of “engaged learning,” but as a revolutionary praxis situated in a broader Marxist tradition of class struggle.¹

Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, first published in 1970, emerged not from elite seminar rooms but from literacy campaigns among Brazil’s dispossessed. His central insight—that the oppressed must become conscious agents of their own liberation through collective critical inquiry—was a direct challenge to both military dictatorship and capitalist ideology. Freire was not simply a progressive educator; he was a theorist of social transformation rooted in the material conditions of the global South.² His pedagogy aimed not to reform existing systems, but to transcend them.

Today, as right-wing movements gain ground across Latin America, the United States, Europe, and South Asia, Freire’s work has again come under attack. From Florida’s school boards to Bolsonaro’s Ministry of Education, Freire has been named explicitly as a threat to national order and moral authority.³ This is not coincidental. What these regimes understand—better than many liberal defenders of education—is that pedagogy is a site of class formation. It either reproduces the hegemony of ruling elites or opens the possibility of its undoing.⁴

The Material Foundations of Critical Pedagogy

Freire’s work cannot be understood apart from the conditions of semi-peripheral capitalism in which it developed. His pedagogy is deeply intertwined with the Latin American tradition of dependency theory and anti-imperialist thought. Like Ruy Mauro Marini and others, Freire recognized that underdevelopment was not the absence of development but its dialectical product: the exploitation of the periphery by the core, maintained through both economic extraction and ideological domination.⁵

Education, in this schema, is not neutral. It serves as an instrument in the reproduction of labor-power and the legitimation of bourgeois social relations. The “banking model” of education—a term coined by Freire to describe the passive transfer of official knowledge—mirrors the logic of capital accumulation: hierarchical, unidirectional, and alienating. Against this, Freire posed a dialogical pedagogy grounded in praxis—reflection and action in dialectical unity. This was not simply a pedagogical technique but a political orientation rooted in class antagonism.⁶

The significance of this idea becomes sharper amid the conditions of contemporary capitalism: the rise of digital labor, platform economies, and algorithmic governance in education. Schooling is increasingly administered not by educators but by software—standardized, surveilled, and monetized. Curricula are shaped by corporate interests; student data becomes a resource to be mined.⁷

Artificial intelligence tools promise “personalized learning,” but often serve to deskill teachers and privatize instruction. The logic is unmistakable: education should produce flexible, depoliticized workers equipped with just enough technical skill to serve profit without challenging power. In this context, Freire’s pedagogy—centered on collective agency, historical consciousness, and the identification of oppression—runs directly counter to the dominant trajectory.⁸

Global Attacks on Critical Education

The repression of critical pedagogy must also be situated in the context of the broader turn towards authoritarianism and neoliberalism. As inequality deepens and traditional institutions lose legitimacy, ruling classes turn to nationalism, myth-making, surveillance, and cultural control. Education becomes a terrain not just of economic policy but of ideological homogenization.⁹

In India, the Modi regime has refashioned the curriculum around Hindu nationalism, erasing caste and colonial resistance. In Brazil, Bolsonaro’s government has vilified Freire directly, calling for his removal from teacher education programs and attempting to criminalize teachers who promote “political indoctrination.”¹⁰ In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s government banned gender studies and placed universities under government-aligned foundations. In the United States, legislative actions seek to criminalize the teaching of race, gender, and class through so-called “anti-CRT” bills and curriculum gag orders.¹¹

These actions are not disparate: they reflect a shared effort to delegitimize education as a space of dissent and reconfigure it as a mechanism of ideological control. They reveal the fragility of neoliberalism’s ideological hegemony: so long as education remains a potential site of critical consciousness, it must be policed. Freire’s pedagogy, which insists on naming oppression and acting upon it, remains fundamentally dangerous to such projects.¹²

The backlash is also mediated through reactionary media, corporate philanthropy, and data-driven ed-tech regimes. Terms like “critical thinking” and “equity” are either gutted of political substance or demonized outright. “School choice” becomes a euphemism for disinvestment, and “parental rights” a code for racial backlash and class resentment. Freire’s insistence that liberation begins with naming the world as it is becomes revolutionary in a landscape saturated with euphemism and ideological fog.¹³

Beyond the Classroom

Despite the institutional assault, Freirean pedagogy continues to thrive outside formal schooling. The Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) in Brazil, for example, operates rural schools embedded in land struggles that center cooperative learning and social consciousness.¹⁴ In Palestine and South Africa, literacy and community education programs link Freire’s dialogical methods to housing rights, feminist organizing, and decolonial resistance.¹⁵

In South Africa, adult education programs grounded in Freirean methods have helped communities interrogate the legacy of apartheid, land expropriation, and ongoing neoliberal extraction. In Palestine, youth programs embed critical inquiry within resistance to occupation and settler violence. In the Philippines, Indigenous Lumad schools integrate Freirean methods into land defense and cultural survival—often under direct threat from state forces.

These movements show that critical pedagogy is not confined to classrooms. It lives in cooperatives, grassroots schools, and informal networks of mutual aid. It thrives in prison education, worker co-ops, and the political education programs of labor movements. What unites these spaces is a common commitment to the idea that education should not prepare people to adapt to oppression—it should prepare them to overcome it.¹⁶

This is a pedagogy of solidarity, not certification; of praxis, not performance metrics. It holds that knowledge is not the property of elites but the collective inheritance of the oppressed. It is precisely this orientation that makes Freire so subversive—he calls not for better schooling within capitalism, but for schooling that renders capitalism obsolete.

Reclaiming Freire for the Long Struggle

In an era when liberal defenders of education retreat into proceduralism and technocratic neutrality, Freire’s radical core must be reaffirmed. His pedagogy is not a workshop model—it is a revolutionary theory of humanization, rooted in struggle.¹⁷ Yet even many progressive institutions reduce his work to buzzwords: “student-centered learning,” “engagement,” “voice.” Stripped of political content, these terms are deployed in service of grants, branding, and hollow reforms.

To reclaim Freire today is to reject this dilution. It is to insist that education is a material battleground. The class war is not only fought on shop floors and picket lines, but also in classrooms, school boards, and digital platforms. Those who control knowledge shape the limits of imagination. If we are to build a socialist future, we must organize minds as well as movements. In this task, Paulo Freire remains not a historical reference, but a strategic guide.¹⁸

To read Freire seriously is to accept a political obligation: to organize with the oppressed, to build counter-hegemonic institutions, and to resist the colonization of consciousness. His project remains unfinished—but it is far from dormant.

Notes

1. Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (Continuum, 1970).

2. Peter McLaren, “Revolutionary Pedagogy,” Monthly Review 57, no. 10 (2006).

3. Vanessa Barbara, “Bolsonaro’s War on Education,” New York Times, May 8, 2019.

4. Henry A. Giroux, On Critical Pedagogy (Bloomsbury, 2011).

5. Ruy Mauro Marini, “Dialectics of Dependency,” Monthly Review 23, no. 3 (1974).

6. Marini, “Dialectics of Dependency.”

7. Audrey Watters, “The Algorithmic Future of Education,” Hack Education, 2017, http://hackeducation.com.

8. Neil Selwyn, “Ed-Tech and the Ideology of Silicon Valley,” Learning, Media and Technology 41, no. 3 (2016).

9. Wendy Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism (Columbia University Press, 2019).

10. Barbara, “Bolsonaro’s War on Education.”

11. Giroux, On Critical Pedagogy.

12. Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

13. MST Brazil, “Our Education Practices,” MST Official Website, 2022, http://mstbrazil.org.

14. South African and Palestinian grassroots education reports, compiled by Education International.

15. McLaren, “Revolutionary Pedagogy.”

16. Giroux, On Critical Pedagogy.

17. Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.