Ana Sofía Cabezas is a Venezuelan activist, political scientist, and the vice president of the Comandante Eterno Hugo Chávez Foundation. In this exclusive interview, Cabezas talks to Venezuelanalysis about this organization’s work in researching and preserving the life and legacy of Venezuela’s former president and revolutionary leader.

Ricardo Vaz: To begin with, can you tell us how the Hugo Chávez Foundation came to be and what its objectives are?

Ana Sofía Cabezas: This foundation was born in 2013 in a painful moment after Chávez’s passing. It responds to the need to safeguard not only the legacy, but also the historical narrative of the Comandante’s life, which is inextricably linked to the genesis of the Bolivarian Revolution.

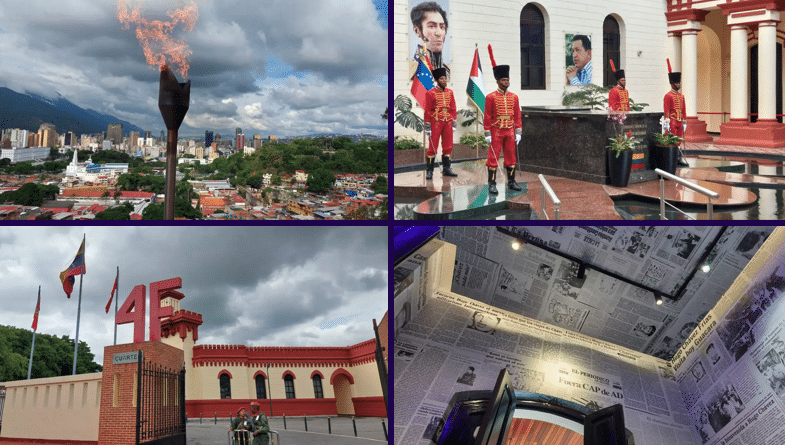

The foundation has its headquarters in this beautiful place that is the Mountain Barracks (Cuartel de la Montaña). This is where Comandante Chávez rests. The mausoleum has become a very special place for those of us who love Chávez, as a way to come and feel closer to him.

There has been a construction of exhibits in different spaces, around the Flower of the Four Elements where the mausoleum is located. We have exhibition rooms, also a space for children’s activities in the Salón del Arañero. And we are making progress in all the work of safeguarding and preserving both the audiovisual material and the physical elements of interest of Chávez’s life.

The objective is to understand Chávez not only as a military officer, or president, but to get closer to his human dimension. We consider that this really matters so that in the future our grandchildren may recognize key elements, identify with the humble Chávez, the Chávez of the countryside (llanos), the patriot, who knows his mission but also sings and laughs. Above all, a historical character who maintained absolute coherence throughout his life and always took responsibility for his actions. If we can sow values like these in future generations, we would be doing something tremendous for the whole world.

RV: Is the foundation attached to any Venezuelan state institution? How is it sustained?

ASC: This is a private foundation, which is maintained through donations. We have a portfolio of projects, and all the people interested in supporting us go through a screening process to be able to participate. The Venezuelan state makes contributions, as do private institutions.

Our initiatives also include agreements with like-minded organizations. We recently signed one with the Fidel Castro Center, to safeguard this important narrative. We want future generations to be able to know the Comandante Chávez that we know, and not the one that appears in Wikipedia.

RV: Can you give us some examples of recent projects or ongoing collaborations?

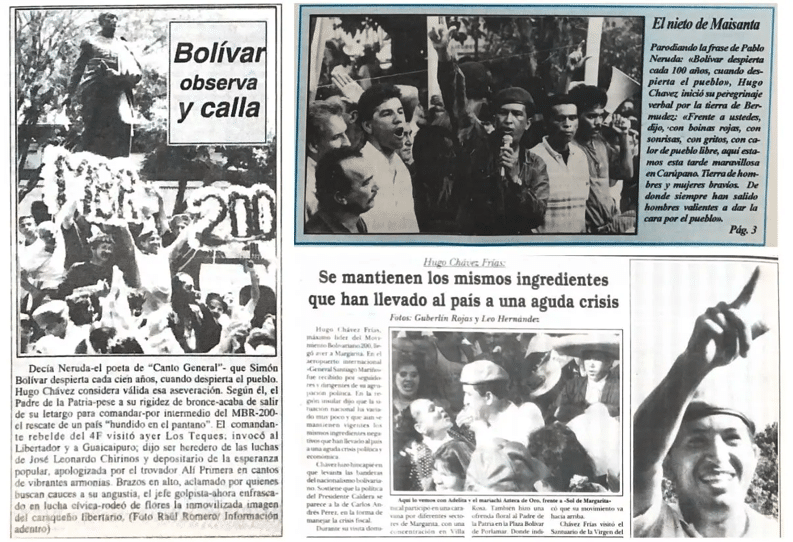

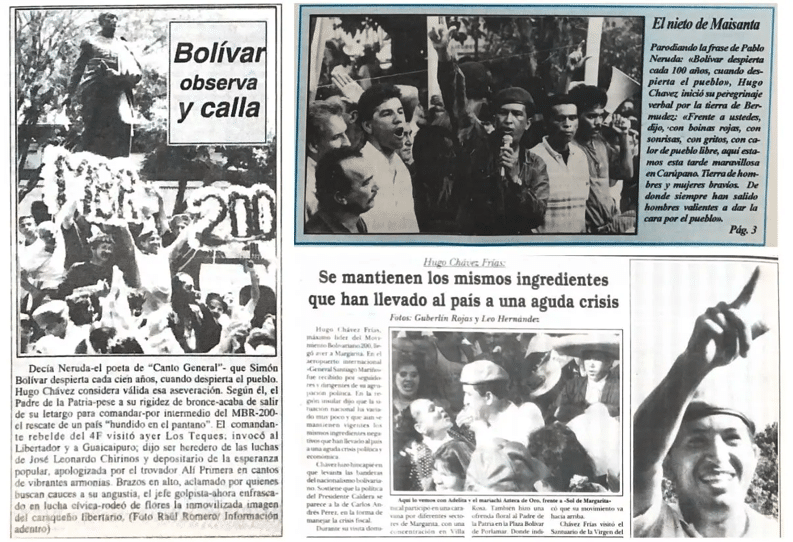

ASC: We recently had, for example, the presentation of Lucas Koerner’s research, an archival tour of the press coverage surrounding Chávez after his release from prison in 1994. This was a very interesting project because it meshed several initiatives in one.

Last year was the 30th anniversary of Chávez’s release, and we began to join efforts that ended up in the publication of La esperanza está en la calle (“Hope is on the streets”), this compilation of newspapers and other periodicals, as well as in the creation of an exhibition hall in collaboration with the Fidel Castro Center, since it also commemorated that first embrace between Chávez and Fidel Castro.

This room has its floor, walls and ceiling fully decorated with material from Lucas’ research as well as from this visit that Chávez made to Cuba in [December] 1994. It is a way of showcasing historical milestones of the revolution, in this case that first meeting between these two giants, but also surrounded by media samples, showing how Venezuelan society responded to the Chávez phenomenon.

Furthermore, we are now producing a children’s book to reach the youngest Venezuelans with this idea the sowing Chávez’s values. This year, which is the 50th anniversary of his graduation from the Military Academy, we are also making progress in the compilation of different research materials.

The Diario del Cadete (“The Cadet’s Diary”), which was our foundation’s first publication, is the diary written by Chávez at the military academy when he was 18 or 19 years old. It is a work that allows us to approach that human dimension, of the young man who misses his family but dreams of taking the reins of Bolívar’s homeland. This book will be available in English this year as well.

RV: The Foundation recently started a podcast project. What is this new initiative all about?

ASC: The Chavistamente podcast has become a beautiful excuse for us because it allows us to complement the exhibitions and the archival work, with testimonial sources. The guests bring stories, anecdotes, and also documentary sources such as photographs, or letters written by Chávez.

So, besides revisiting these memories, the podcast also feeds this narrative that we are building. For example, we have recently featured comrades of the MBR-200 [Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement-200, Chávez’s clandestine political movement], who were with Chávez when he left Yare prison and the whole political project, the democratic proposal, began to take shape. And these stories, of the people who ran to greet them, we cross-checked with the press sources.

Another advantage of the podcast is that it shows the Comandante behind the scenes. Recently we interviewed journalists who accompanied him on an international tour, and they told stories how Chávez would come to congratulate them for their work, or that he was concerned if everyone had eaten. So, we have a president visiting 10 countries, with little sleep, dealing with geopolitical issues, but he does not lose that human dimension of approaching journalists and offering them coffee.

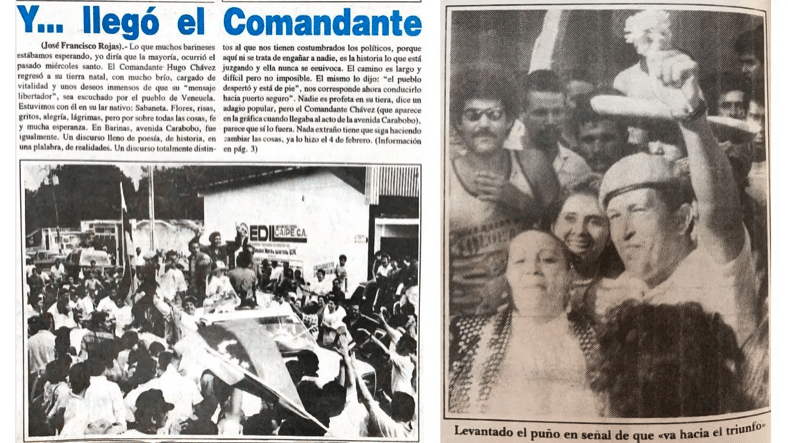

Press reports on Chávez from his political ascent in the 1990s. (Biblioteca Nacional de Venezuela/Lucas Koerner)

Press reports on Chávez from his political ascent in the 1990s. (Biblioteca Nacional de Venezuela/Lucas Koerner)

RV: Going back to the period after Chávez’s release from prison, it is very interesting to see, and the Foundation’s research work shows it, that destiny was far from written. Chávez somewhat disappeared from the news cycle in 1995. How did the process unfold at that time?

ASC: This is exactly right. The big media silenced him, but he continued doing that grassroots work. “Big TV stations will not cover this, so I will go to the community radio stations.” Or he would meet in a remote village or a town square where no politician would go.

A very illustrative example is what happened when Chávez was sent to Elorza (Apure state), precisely 40 years ago. The armed forces had detected the subversive movement he was leading and to neutralize it they sent him to Apure, believing that by posting him on the most remote corner of the country, the insurgency would end.

There was nothing there, just a few campesino and Indigenous communities. And what did Chávez do? He organized the people, he fought for Indigenous peoples’ rights, he was even a guest of honor at the famous Elorza festivities. He encouraged the people to grow food too. Because, with this being an area bordering Colombia, defense was important, but so was self-reliance.

So his response to the media silence in 1995, in the face of those who thought he was being neutralized, was similar. The Comandante’s actions always had a thread of coherence.

RV: Chávez developed much of his political vision while in the Armed Forces, which was also the setting of a battle for hearts and minds. What was the influence of this period on his thinking?

ASC: Episodes such as the Apure one I was talking about allowed Chávez to build a more progressive understanding of the notion of sovereignty. The Armed Forces had a nationalist perspective, with initiatives such as the Andrés Bello training program, which included a lot of state theory, philosophy and history.

Chávez came out of the academy with that calling to serve the homeland, but then he was disappointed. He describes it in his Diario de Operaciones (“Diary of Operations”) from 1977, for example that the officers did not spend time alongside the rank-and-file troops. At that time there were also operations against the guerrillas and Chávez began to witness contradictions, how the army persecuted the people. He begins to question himself and concludes that the army soldiers, unlike the guerrillas, do not know what they are fighting for. It is a complex moment in his life.

Chávez even considered resigning from the Armed Forces. Fortunately, his older brother Adán convinced him not to do so, otherwise history would not have been the same.

Press reports on Chávez from his political ascent in the 1990s. (Biblioteca Nacional de Venezuela/Lucas Koerner)

Press reports on Chávez from his political ascent in the 1990s. (Biblioteca Nacional de Venezuela/Lucas Koerner)

RV: A significant part of the foundation’s research work focuses on the period prior to Chávez’s election as president. What is the purpose of this approach?

ASC: First of all, Chávez’s electoral triumph and the period that followed are naturally more documented, there is much more information from his time in the presidency.

However, the previous period has a special importance in understanding the man, the soldier, the fighter. So in the last few years we have dedicated ourselves, with plenty of digitalization work, to this period leading up to the 1998 popular victory. Then we will move on to what came after as well.

RV: The Foundation’s work is a sort of curatorship of Chávez’s memory. How do you manage, on the one hand, not to introduce biases, and on the other hand, to transmit an image that is useful for the present? In other words, a Chávez that remains relevant and not frozen in the past.

ASC: For us, the important thing is that the sources of information related to Comandante Chávez and the genesis of the Bolivarian Revolution are available for the study and research of any and all who wish to do so.

We are absolutely sure of the man that Chávez was, of his human quality, of his leadership, of his character as a person, and we are confident that anyone who begins to study his life, who delves into the sources and reads or listens to testimonies, will understand the importance and dimension that Chávez had. And that he continues to have.

Our intention is that this knowledge be openly available, that the powers that be do not take over the memory of Chávez and deprive future generations of knowing this history, this man.

How do we ensure it stays relevant? It is quite simple. Sometimes you just have to listen randomly to an Aló Presidente [broadcast] and it will seem like Chávez is talking about things unfolding here and now. For example, in the Flower of the Four Elements there is a Palestinian flag. We listen to any speech by Chavez on Palestine and we see an analysis that has been fully vindicated, it was even ahead of other contemporary leaders.

Just as capitalism and imperialism continue to exist, Chávez’s project remains valid and useful to confront reality and envision the future. Furthermore, his messages contain basic principles, such as unity in struggle and irreverence in debate. In other words, maintaining unity but remembering who is the most dangerous enemy, the historical enemy.

Chávez’s closing campaign rally on October 4, 2012. (Presidential Press)

RV: Chávez had that capacity to jump back and forth between topics with great depth, but sometimes it happened that some important point ended up overlooked due to the political context at the time. For people getting to know Chávez, how do you explain this legacy, which also has deep theoretical contributions?

ASC: Chávez’s speeches normally had a historical background and a very deep message, especially from his humanism. So that is an important perspective, the sowing of values. And it is important that this valuable information is not in some confidential file, but is out there in the Aló Presidente broadcasts, which we hope to soon have more organized so people can search through them.

These memorable broadcasts are fundamental because they showcase Chávez’s oral prowess. I believe it is his essential element as an organic intellectual, perhaps the most important such figure since Bolívar. An organic intellectual who completely surpassed the academic intellectuals of his time.

Anyone around 40 years old in Venezuela will remember that before Chávez, politicians stood up, read written speeches and that was it. The Comandante also came to change the way of doing politics, of communicating it, of sharing it. This became deeply ingrained in the Venezuelan people, even among those who opposed him. This change of methods ends up being as important as the policy changes themselves.