Tomorrow, a key election takes in the G7 economy, Japan. The focus is on whether the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior partner Komeito, which together suffered a major defeat in last autumn’s lower House of Representatives election, can maintain a majority in the upper House of Councillors. The coalition government must win 50 of the 125 seats (half of the House seats) that are up for grabs. The latest opinion polls suggest that various minority opposition parties are taking around two-thirds of the potential vote among them, while the governing parties are getting only 32%.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, who heads the LDP, has intensified his rhetoric on issues appealing to conservatives, the core LDP base. He has emphasized the necessity of revising Japan’s pacifist constitution, a long-held goal of the LDP to remilitarize Japan, and has talked tough on opposing Trump’s proposed 25% tariff on Japanese exports to the U.S.: “Do not underestimate us. Even if it is an ally that we are negotiating with, we must say what needs to be said without hesitation.” Ishiba is appealing to the ‘populist’ right, just as all ‘mainstream’ politicians in the G7 economies now do. In Japan, the ‘populist’ right is represented by the Sanseito party, which is against immigration and foreigners under the slogan “Japanese First” and has gained support among younger voters.

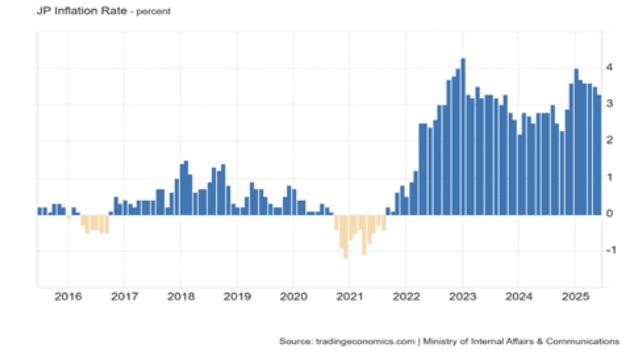

But those are not the main issues concerning voters. Instead, it is dissatisfaction with rising inflation, low wage growth and high taxes, leading to a wave of support for previously marginal parties that have pledged more government spending and cuts to the sales tax on all goods. The LDP has promised cash handouts and other measures to lower energy prices.

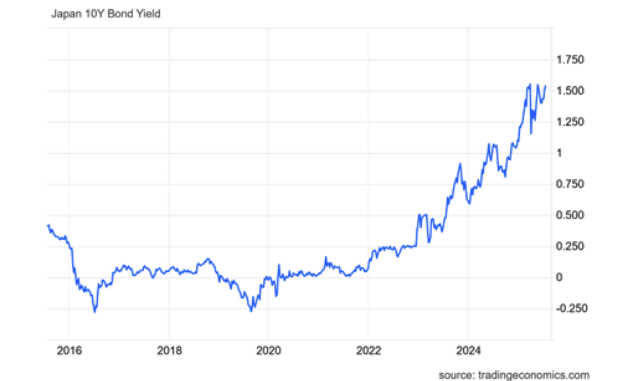

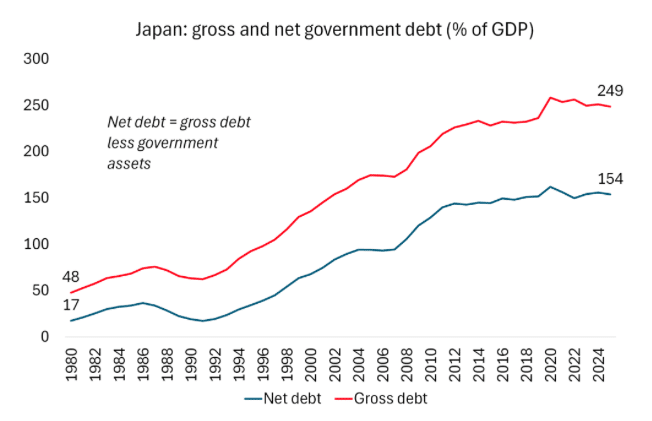

But these promised handouts can only increase the government’s budget deficits and the humongous public sector debt that Japan has. As a result, financial investors have been selling off government bonds: the yield on ten-year bonds has hit its highest level since the global financial crash of 2008.

The opposition parties are running their campaigns on attacking the rising inflation rates and calling for a cut in the 10% sales tax and the 8% food items tax to reduce the cost of living. But the sales tax is the biggest source of government revenue. In fiscal 2025, it collected 25 trillion yen ($160bn), or 21.6% of total revenues. Halving the tax rate would cut revenues by over 10 trillion yen.

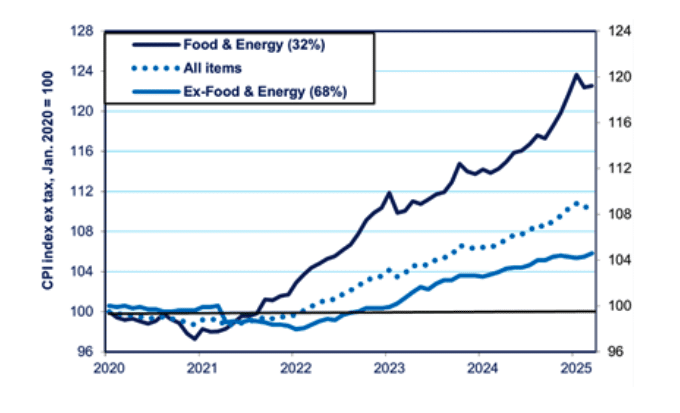

Japan used to have a near zero rate of inflation but in an attempt to revive the economy, the government and the Bank of Japan deliberately tried to boost inflation to encourage companies to invest and reduce the real burden of debt. But all that has done is eat into the living standards of Japanese households.

According to the polls, 48% of the public says combating inflation is the top issue, followed by social security at 33% and economic growth at 30%. Voters want a cut in the sales tax but do not want the revenue loss to be compensated for by reductions in social security benefits as the government has suggested would be necessary.

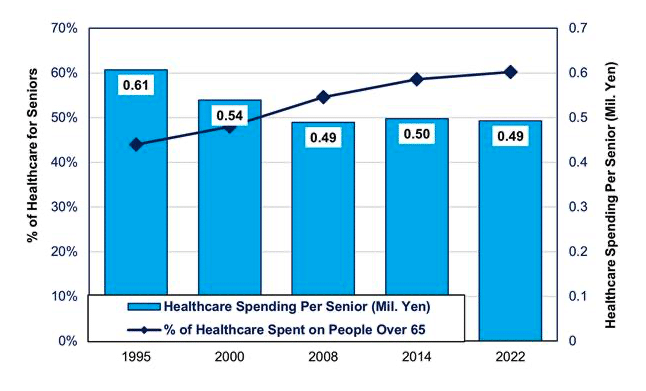

Source: Katz

As in all G7 economies, over the decades, Japanese governments have adopted neoliberal economic policies aimed at reducing pensions and welfare benefits. Richard Katz has pointed out that the LDP coalition has lowered social security benefits for seniors from ¥2.9 million ($20,000 at today’s exchange rates) in 1995 to just ¥2.1 million ($14,500) now, a 30% decrease in price-adjusted terms. In addition, government spending on healthcare for each person over the age of 65 has been reduced by almost a fifth over the past 30 years.

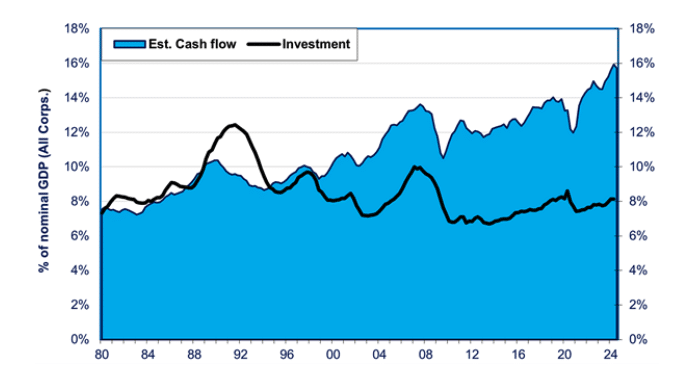

Source: Katz

At the same time, the corporate profits tax has been slashed from 50% to just 15%. Profits have doubled from 8% of GDP to 16% but corporate tax revenue for the government has tumbled from 4% of GDP to 2.5%. These cuts in corporate profits tax have not led to improved business investment growth. Instead, companies hoarded the cash or invested in government bonds and the stock market.

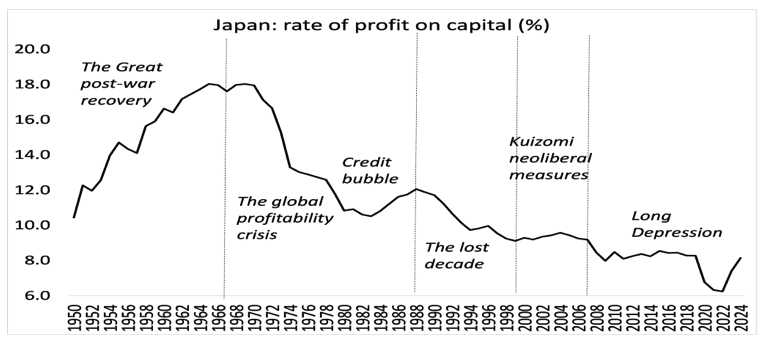

Source: Katz

The key to the failure of these neo-liberal measures to boost corporate investment and end the stagnation of the Japanese economy since the 1990s is the decline in the profitability of capital investment. Japan’s profitability of capital has fallen more than in any other G7 economy.

Source: EWPT and AMECO series, author’s calculations

The Japanese economy has stagnated (in real GDP), continually teetering on outright recession. So investment and consumer demand has been weak. This is particularly the case with wages. Indeed, it has been a feature of the last 25 years that wages have remained stagnant, while profits have risen. This is the product of the neo-liberal policies adopted by successive governments in trying to reverse the long-term decline in the profitability of Japanese capital, with only limited success.

Even though the official unemployment rate is near all-time lows, as in other major economies, there is more ‘slack’ in the labour market than the 2.5% unemployment rate would otherwise indicate. The aggregate number of hours worked is still 2.8% below the pre-pandemic level. Companies are filling gaps in the ranks of their workforces with part-time workers at lower wages. Unemployment is low because of the massive shrinkage in the working-age population, now declining at about 550,000 per year.

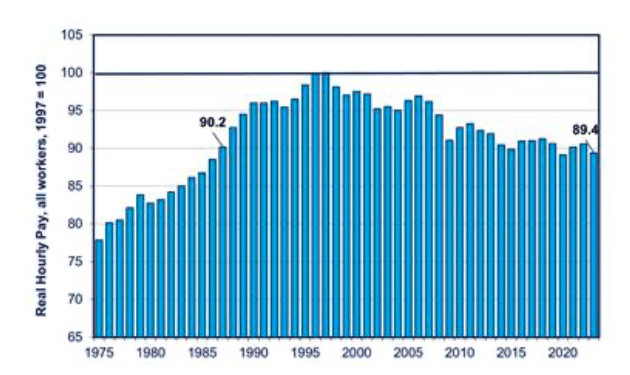

The impact on the labour market has been compensated for by a rise in female employment, but female employees work in lower wage areas and receive lower wages than males. This keeps wage share down and profit share up. Indeed, labour’s share of Japan’s national income has been falling since the end of the Japanese boom period of the 1980s; from 60% to 55% now. The median hourly pay of a full-time worker in Japan is no higher than in 1993. And the average real hourly wage of all Japanese workers—not just full-timers—is down 10% from its 1997 peak.

Source: Katz

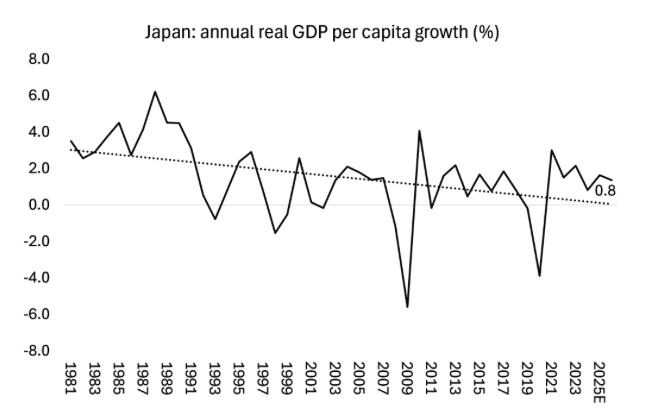

The big long-term issue is Japan’s population. It has been falling and ageing. That allows per capita income growth to grow more than total GDP growth; per capita Japan’s real GDP is up 10.8% since 2010, while real GDP is up 9.6%. But per capita real GDP growth is also slowing.

Source: IMF

Those in work are overworked. Japan invented the term karoshi–death from overwork–50 years ago, following a string of employee tragedies. The large corporates are promoting the idea of a four-day week to relieve this pressure and increase productivity. But there is little sign that this or any other measure is working to raise productivity. Productivity growth is non-existent.

The reason is clear. Business investment growth is very weak. Japan’s corporations may have increased profits at the expense of wages, but they are not investing that capital in new technology and productivity-enhancing equipment. Real investment is no higher than in 2007. Public investment (about one-quarter of business investment) is static. Japanese capital’s image of innovating technology appears to be long gone. The mainstream measure of ‘innovation’ , total factor productivity (TFP) has faded from over 1% growth a year in the 1990s to near zero now, while the huge capital investment of the 1980s and 1990s is nowhere to be seen. So Japan’s ‘potential’ real GDP growth rate is close to zero.

Prime ministers come and go: from Abe to Kishida to Ishiba, but nothing changes. Japan has run permanent government deficits, spending it on construction and other projects and yet Japan’s economy has continued to stagnate. Japan’s huge public debt ratio will not lead to a financial crisis, as the bulk of this debt is owned by the Bank of Japan and the major banks, but it still expresses the failure of the private sector to invest.

Source: IMF

The Upper House election takes place as Japan’s export engine is spluttering and just as U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs will start to hit key sectors such as automobiles and steel from 1 August. Tokyo has so far failed to reach a trade agreement with the U.S., despite seven trips to Washington by Japan’s trade envoy Ryosei Akazawa.

Japan’s economy contracted in the first quarter and the latest trade figures suggest that a second consecutive contraction in Q2 is increasingly likely, meeting the definition of a ‘technical recession’. If the LDP-led coalition loses its majority in the Upper House, then it may be forced to hold a general election, with the economy stagnating and the government in disarray.