Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In July, a few days after the centenary of Frantz Fanon’s birth, I had lunch with his daughter, Mireille Fanon Mendès-France. When I commented that Fanon had died so young, at thirty-nine, Mireille corrected me: ‘No, thirty-six’. Even three more years would have been a gift – to him because he might have been able to finish other work and spend more time with his family, and to us because we might have gotten the book that would have come after The Wretched of the Earth – perhaps one on how to construct a national project that would not succumb to the pitfalls of narrow nationalism. But that was not to be.

Thinking of my conversation with Mireille and the legacy her father left behind, I asked the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research team to help me make a list of revolutionary leaders and intellectuals who died before their fortieth birthday. The names came tumbling out, and before I knew it, I had several pages before me, a digital memorial to people who had been assassinated for their views, the list moving from Mozambique’s Josina Machel (25 years old) to Cuba’s Che Guevara (39 years old). I was tempted to publish a short version of the list in this newsletter, but I held back. How does one shorten a list that is already inadequate, since so many people, leaders, and intellectuals in so many localities have been assassinated by the immense structures of repression set up by the imperialist system?

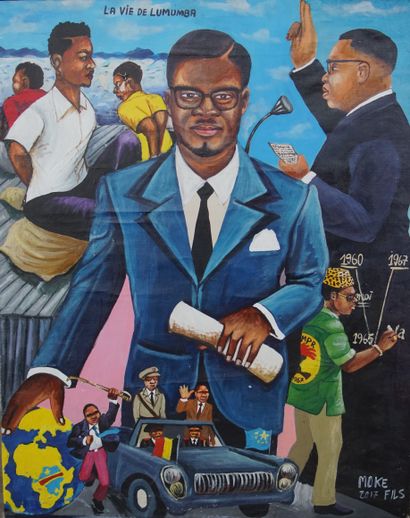

Moke Fils (DR Congo), La Vie de Lumumba (The Life of Lumumba), 2017.

In lieu of producing an inadequate list, we will stay for a moment with Fanon, who published two books during his short lifetime: Black Skin, White Masks in 1952 and The Wretched of the Earth, published in 1961, just a few months before his death. Two more, A Dying Colonialism, written in 1959, and Toward the African Revolution, a collection of essays written between 1952 and 1961, were published posthumously in 1964.

It is impossible to take this oeuvre and say that this is Fanon, that this is all he would have produced, and that everything he did – his psychiatric practice, his work for the Algerian liberation movement – is all he would have contributed. Scholars treat Fanon as a finished collection, but in fact he had not even reached his peak. The clarity of the argumentation in his final book opened new lines of enquiry that he would have followed up on after 1961 if his life had not been cut short – especially in light of the evidence that soon emerged about the internal and external limitations placed on post-colonial states.

Five years ago, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research published a dossier on Fanon, The Brightness of Metal (March 2020), which made a provisional case for Fanon’s thought on national liberation. But it is only provisional – Fanon’s theory remained incomplete at the moment of his premature death.

Elements of the book that would have come after The Wretched of the Earth are evident in the essay Fanon wrote after the assassination of thirty-five-year-old Patrice Lumumba on 17 January 1961. Published in Afrique Action in February 1961, the argument in ‘Lumumba’s Death: Could We Do Otherwise?’ is summarised in one powerful paragraph:

Our mistake, the mistake we Africans made, was to have forgotten that the enemy never withdraws sincerely. He never understands. He capitulates, but he does not become converted.

Our mistake is to have believed that the enemy had lost his combativeness and his harmfulness. If Lumumba is in the way, Lumumba disappears. Hesitation in murder has never characterised imperialism.

Indeed, imperialism is never generous or humanitarian.

Barthélémy Toguo (Cameroon), Déluge IV (Deluge IV), 2016.

In his essay on Lumumba, Fanon also mentions two names but does not go into any depth about them: ‘Look at ben M’hidi, look at Moumié, look at Lumumba’.

Mohammed Larbi ben M’hidi (1923–1957) was one of the six founding members of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). Known as ‘Larbi the Wise’, he was the commander of the Wilaya V military zone in the Oran region and later led the FLN in the Battle of Algiers. He was captured in February 1957, brutally tortured, and executed a month later at the age of thirty-three. France would not tolerate this upright Algerian.

Félix-Roland Moumié (1925–1960) led the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon throughout the country’s independence struggle, which broke out in 1955. As in Algeria, French repression in Cameroon was diabolical, resulting in the killing of tens of thousands of people in harsh attacks on civilian centres. This history has been largely forgotten. Moumié was assassinated in Geneva by a member of the French security services, who poisoned him with thallium. He was thirty-five.

The deaths of M’hidi, Moumié, and Lumumba – all of whom Fanon knew personally – underlined the brutality of imperialism. If a radical appears on the horizon to lead a people to sovereignty, then the radical cannot be allowed to survive. Lumumba was a radical, a man ‘sold to Africa’, Fanon wrote, meaning that his heart was with the people of Africa and had not been sold out to imperialism. That is why he was killed.

Baya Mahieddine (Algeria), Musique (Music), 1974.

Belgium, Britain, France, and Portugal refused to withdraw from their African colonies peacefully. They used every tactic, including those used by the Nazis and the Japanese in World War II which were subsequently declared to be war crimes during the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials, respectively. If the definition used in these trials were applied to the colonial wars from Algeria to Cameroon, the military and civilian leaders of these European countries would have been hanged.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Imperial Japanese Army, for instance, was hanged in 1946 after the Tokyo tribunal found him guilty under the principle of command responsibility (later known as the Yamashita Standard) for atrocities committed by his troops against civilians in the Philippines. If this standard were applied consistently, British Field Marshal Gerald Walter Robert Templer would have been hanged for his role in the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960), including the use by the British of internment camps and herbicidal warfare against the general population, which prefigured the later use of Agent Orange by the US in Vietnam.

By the same measure, French generals Jean-Marie Lamberton and Max Briand would have been hanged for their role in the war in Cameroon (1955–1964), where French forces used extreme brutality against insurgents and civilians alike, including documented massacres and reported use of decapitations as psychological warfare.

But, of course, they all died with medals wrapped around their chests.

It is important to recall that toward the end of the war, the French tested their nuclear bomb in Algeria’s Reggane, in the Sahara Desert, on 13 February 1960, making France the fourth country in the world to possess nuclear weapons. France refused to join the Partial Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty of 1963. Algeria won its independence in 1962, but France retained a five-year lease to continue nuclear weapons testing in Reggane, which it did until 1966. After that, France shifted its tests to the Fangataufa and Moruroa atolls in the Pacific Ocean, where it conducted 193 nuclear tests over the next thirty years.

As France tested its atomic bombs in Reggane, Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth: ‘those literally astronomical sums of money which are invested in military research, those engineers who are transformed into technicians of nuclear war, could in the space of fifteen years raise the standard of living of underdeveloped countries by 60 per cent’. While he wrote about the tests in economic terms, he could just as well have written about them in terms of political threats: if assassinations didn’t work, the atomic bomb, too, was available for France to use against its rebellious colonies.

Fanon met Lumumba and Moumié on behalf of the Algerian provisional government at the 1958 All-African People’s Conference organised by Ghana’s Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah in Accra. They talked about the necessity of national liberation struggles, how to best protect themselves from the brutality of imperialist force, and how to advance beyond the tentacles of the neocolonial structure. Fanon was interested in the creation of an African Legion, a military force for the continent’s wars of liberation that would be trained by the Algerians and their allies. In his notes from these meetings, Fanon wrote about Moumié’s death:

An abstract death striking the most concrete, the most alive, the most impetuous man. Félix’s tone was constantly high. Aggressive, violent, full of anger, in love with his country, hating cowards and maneuverers. Austere, hard, incorruptible. A bundle of revolutionary spirit packed into sixty kilos of muscle and bone.

These sentences about Moumié could very well define Fanon.

The official record of Fanon’s death is bronchial pneumonia, but that is just what it says on the certificate. There was a man from the Central Intelligence Agency, C. Oliver Iselin, present when he died. So it goes.

Warmly,

Vijay