Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

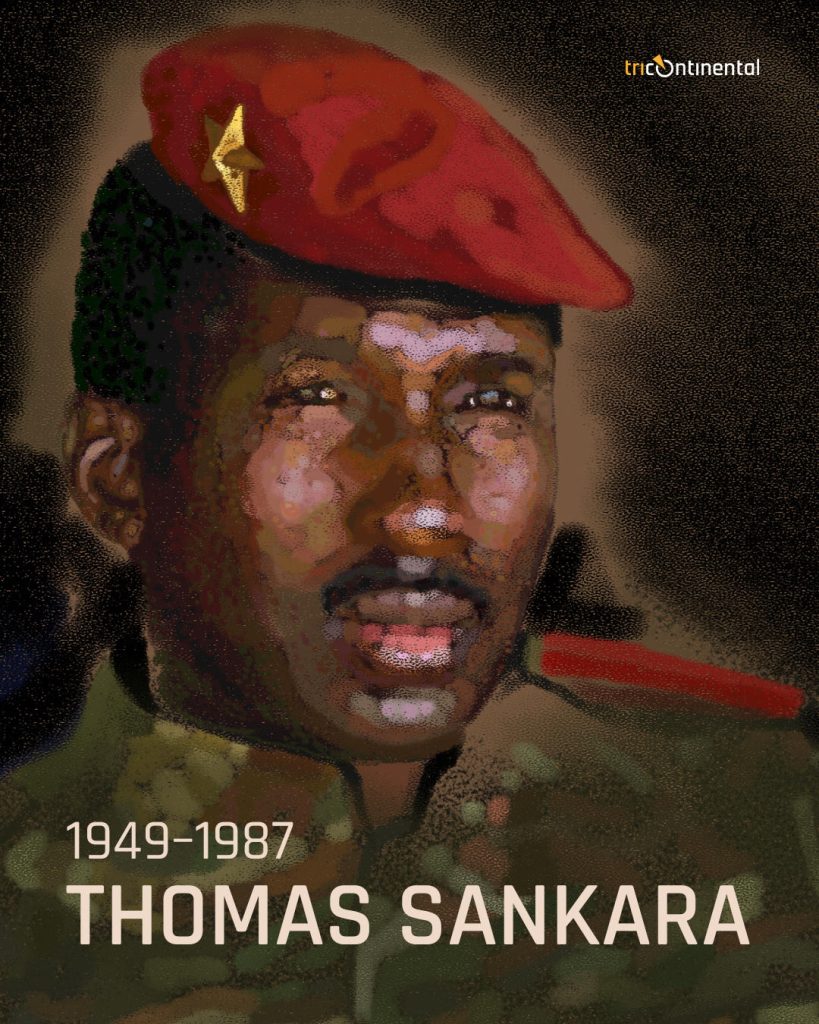

In the months after the 1987 coup in Burkina Faso that killed President Thomas Sankara, screen printers in the capital, Ouagadougou, began to churn out shirts with Sankara’s face on them. The image soon spread throughout the country. Blaise Compaoré, Sankara’s former minister of justice, went on to rule the country until 2014. He was suspected from the outset of orchestrating Sankara’s murder, but it would take the Burkinabé courts until 2021—2022 to find him guilty. By then, he had long fled to Côte d’Ivoire, where he remains a fugitive. Throughout his time in office, Compaoré claimed to be a follower of Sankara—a political legacy he could not afford to disavow.

Having joined the military at twenty, Compaoré became a close comrade of Sankara and participated in the 1983 coup that brought him to power. That he would turn against his mentor (only two years his senior) was not predictable to those who did not appreciate the power of wealth in an extraordinarily poor country. Compaoré comes from the province of Oubritenga, which has the highest poverty rates in the country. Sankara’s agenda had been to reverse Burkina Faso’s colonial heritage—first by renaming it from the Republic of Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, the Land of the Upright People—and Compaoré had been part of that journey. But personal desires are sometimes hard to fathom, and they are often what foreign intelligence agencies prey upon.

Saïdou Dicko (Burkina Faso), The Water Statue, 2020.

Burkinabé politics have long been punctuated by coups—in 1966, 1974, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987, 2014, and 2022—yet there is nothing unique about the country that explains their punctuality. Since 1950, at least forty of Africa’s fifty-four countries have experienced a coup—from the July 1952 overthrow of Egypt’s monarchy by the Free Officers (led by Gamal Abdel Nasser) to the August 2023 coup in Gabon led by General Brice Oligui Nguema. A coup is only the outward manifestation of the neocolonial structure in which states such as Burkina Faso and Gabon exist—colonialism, particularly the French variety, never allowed the state to develop beyond its repressive apparatus or permitted the formation of a national bourgeoisie that was economically and culturally independent of Western capital. The absence of a developmentalist state and an independent bourgeoisie meant that elites in such countries functioned as intermediaries: they allowed foreign companies to siphon off national wealth, earned a modest retainer for that service, and prevented the formation of a genuine democratic political process, including the democratisation of the economy through trade unions. This was the neocolonial trap.

Countries in this trap do not have the political space to easily overcome their internal class realities and their lack of sovereignty vis-à-vis foreign capital. With few livelihood opportunities, many young people from small towns and rural areas join the military. It is in the military that they are able to discuss the distress in their countries and—as in the case of Sankara—incubate progressive ideas. Sankara’s 1983 rupture with his country’s colonial history enabled him to put in place several of these ideas: land redistribution to encourage food sovereignty; resource nationalisation to combat foreign plunder; regional military alignments to defend against imperialist meddling; rejection of foreign aid that undermined national sovereignty; and the advancement of national unity and women’s emancipation. For four years, his government pursued this progressive agenda while challenging the International Monetary Fund’s debt-austerity regime. But then he was assassinated.

It is important to remember that Blaise Compaoré was ousted in 2014 by a popular uprising led by residents of the non-lotissements (informal settlements), youth movements, and other civic forces. That was the mood. But the revolt was not able to consolidate power, and the benefits went to a weak civilian government, competing military groups, and, eventually in parts of Burkina Faso, to al-Qaeda factions emboldened by the 2011 destruction of the Libyan state by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Fulfilling the mandate of the 2014 popular protests was the stated aim of the January 2022 military coup by the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (Mouvement patriotique pour la sauvegarde et la restauration, MPSR), a group of officers dedicated to Sankara’s legacy. The MPSR was first led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba and, after his September 2022 overthrow, by Captain Ibrahim Traoré. This, it appeared, was the resurrection of the Sankara rupture.

From Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes our latest dossier The Sahel Seeks Sovereignty (August 2025). Researched and written by our Pan-Africa team, it offers a historical assessment of the politics not only of Burkina Faso, but of Mali and Niger as well—now united as the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). The word ‘sovereignty’ in the title defines our argument: whatever elections these countries held in the past, they neither deepened the democratic potential in their societies nor did they strengthen their economies against foreign influence. All three AES states are rich with gold mines, and Niger in particular is endowed with high-quality yellowcake uranium—yet none has been able to fully control its resources or economic institutions, subordinated as they have been to the French monetary system and Western corporations. You do not need an open political dictatorship to suffocate the sovereignty of a country such as Burkina Faso: Compaoré won elections with 100% of the vote in 1991, 90% in 1998, and 80% in 2005 and 2010, but this was scintillantly undemocratic. The MPSR, carrying forward Sankara’s agenda and the mood of the 2014 protests, is far more democratic than the system that elected Compaoré.

The 2014 uprising in Burkina Faso came not only from the non-lotissements, but also from the nightclubs. In 2013, reggae artist Sams’K Le Jah (Karim Sama) and rapper Smockey (Serge Bambara) founded Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizens’ Broom), a grassroots movement named for Sankara’s civic street-cleaning campaigns and dedication to sweep away the old elite and foreign capital. In nightclubs across the country, Sams’K Le Jah held aloft Sankara’s heritage:

Sankara, Sankara, Sankara, my president,

Sankara, Sankara, Sankara from Burkina.He came as a man of integrity to build a dignified Africa.

Through your supreme sacrifice, you gave meaning to my life.

Your blood is the sap that nourishes forever

our hope for a dignified Africa.

Warmly,

Vijay