The Haka Party Incident

Directed by Katie Wolfe

Tasman Ray Productions, 2024

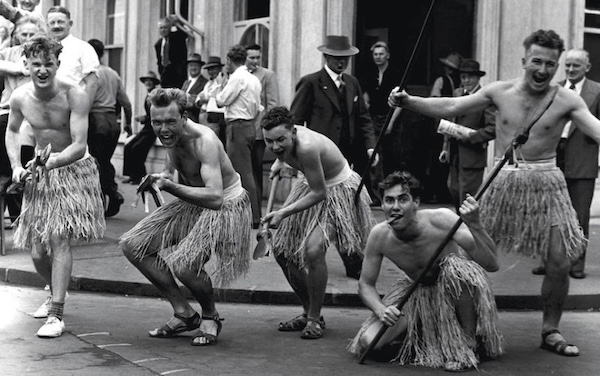

For decades at the University of Auckland, white engineering students held an annual “haka party,” donning brownface and performing a mockery of the haka—a traditional Māori dance—throughout Auckland. By 1979, a small group of young Māori activists, He Taua, were fed up with politely requesting that the engineering students stop. On the day the party was planned, He Taua arrived at the engineering students’ common room, shouted, demanded they remove their brownface, wipe off crude moko—Māori tattoos—and cancel their drunken tour of the city. The confrontation reportedly lasted only about five minutes before He Taua left. Almost immediately afterward, however, the activists were stopped in traffic and arrested by Auckland police. In the hours and weeks that followed, they were brutalized by police, finding themselves at the forefront of years-long struggles for Māori civil rights.

Director Katie Wolfe’s wry, biting, and energizing documentary on these freedom fighters, The Haka Party Incident (2024), compiles interviews with both the students and activists involved, 45 years after the event. Following in the footsteps of Wolfe’s stage play of the same name, the film is as full of heartfelt love for Māori people and culture as it is brimming with staunch defiance toward the racist contradictions embedded in settler-colonial societies. New Zealanders’ readiness to mock Māori people through caricatures of the haka is both shocking and contemptible. Yet Wolfe keeps the wider stakes in view: the incident took place against a backdrop of state violence aimed at eradicating real Māori people and their ways of life. The Haka Party Incident draws that violence, injustice, and absurdity into sharp focus. In microcosm, it reveals the asymmetrical ultimatums that Pākehā (non-Māori) and Māori face under colonial rule: for the former, be racist or not; for the latter, be Māori, or ignore racism and assimilate into settler society.

Wolfe approaches the incident with a wide, deliberate lens. In a director Q&A after the film’s screening at imagineNATIVE in Toronto this June, she shared that she spent two years searching for former haka party participants willing to appear on camera. While some interviewees had changed their minds in the months and years after the incident, viewers may still reflexively (and justifiably) scoff at those Pākehā who defend—or at least do not regret—their participation. Wolfe does not portray them judgmentally; their words, and their repeated defence of their choices, speak for themselves. This is not to suggest that any of the men present that day should be excused, but to point out that stopping at condemnation would do a disservice to Wolfe’s work in finding Pākehā willing to flesh out the story with their testimony.

Although Wolfe treats the story with due gravity, her subjects—especially the He Taua interviewees—bring abundant humour to the film, which she skillfully amplifies through editing. In one sequence, former engineering students describe the encounter as “traumatic,” only for the scene to cut to Ben Dalton, one of the He Taua, bluntly calling it “pretty tame.” The contrast lands with forceful humour.

Even in the aftermath of the incident, as University of Auckland students gathered to discuss racism on campus, He Taua members recall attendees breaking into a rendition of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Humour here is not used to placate the viewer or catch them off-guard; it reflects the He Taua perspective that certain elements of the colonial apparatus are as ridiculous as they are insidious. Māori humour and laughter cannot be stamped out—just as we cannot credibly believe that the engineering students’ brownface was an authentic haka.

The documentary ends as optimistically as it can, given that for every step forward, New Zealand seems to take two steps back. We see the University of Auckland’s engineering department learning their own genuine haka from an expert choreographer. Yet even as these Pākehā demonstrate a commitment to learning and preserving Māori traditions, the New Zealand government introduces a now-infamous bill to abolish the Treaty of Waitangi, which grants Māori special sovereign rights.

The film screened in Toronto just a day after Māori MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke was suspended from New Zealand’s parliament following what became known as her “haka incident.” Maipi-Clarke had performed the Ka Mate haka in protest of the bill that would void the Treaty of Waitangi, thereby abolishing Māori rights. Her suspension was justified on the grounds that the haka was “intimidating.” Yet haka are performed in a variety of contexts, including occasions where political counsel is offered. At the screening I attended, a few Māori audience members performed Ka Matein Wolfe’s honour. Because the haka demands deep respect and ceremony, the rationale for Maipi-Clarke’s suspension is neither sensible nor acceptable.

Here lies a fundamental problem with how settlers understand the haka: it is “intimidating” unless they are the ones performing it in mockery. When Pākehā use it to ridicule Māori people, the act is treated as too frivolous to warrant pushback or consequences. Māori, however, are punished both for doing the haka on their own lands and for objecting to its misuse.

The Haka Party Incident is both a metonym and a contained story. Its dexterity lies in allowing the complexity of its subjects to shine while also turning important questions back on the viewer and the lands they occupy. For settlers on Turtle Island especially, the lesson is clear: there can be no justice while Indigenous peoples and their traditions are erased.

Jessie Krahn is a writer, Elia scholar and PhD student in Cinema Studies at York University. She received her MA in English from the University of Manitoba in 2023. Her SSHRC CGS-M-funded thesis research focusing on authorship and social media, especially on the ways authors’ anticipation of audience responses arises through the formal components of internet video, received the Professor Sidney Warhaft Memorial Award for best critical thesis from a graduating Master’s student in English.