If there was one word for the dominant challenge afflicting “the left” and African/Black radicals, it is confusion. Assaults on the livelihoods of the masses of our people, the destruction of the neoliberal status quo via genocide abroad and accelerated austerity in the U.S., cooptation of radical rhetoric by Black misleaders and the liberal elites, increasingly fascist popular media and entertainment, reactionary debates on social media amplified by tech, and bad faith organizational conflicts that halt attempts to develop grassroots power–all of these conditions fuel the flames of confusion that are consuming our movements and organizations.

It’s not our goal here to determine where this confusion stems from, whether it is intentionally spread or organic or both, but one thing is clear: in this intense and ongoing battle of ideas, there’s a pressing need for clarity. For African people, particularly those of us within the borders of the so-called United States, fighting for our self-determination, human dignity, and survival requires collectively overcoming this confusion. This is a task that requires understanding our material conditions in this capitalist-imperialist-white supremacist world system, and taking an approach that has the capacity to lead to revolutionary change.

When we ask the question today about the relevance of Marxism to black people, we have already reached a minority position, as it were. Many of those engaged in the debate present the debate as though Marxism is a European phenomenon and black people responding to it must of necessity be alienated because the alienation of race must enter into the discussion… (Walter Rodney, Decolonial Marxism)

Socialist, Anarchist, Liberal, Communist, Pan-Africanist—these are not just labels. They represent foundational frameworks that shape how we understand the world and our place within it. For us, Marxism, as a living and evolving tradition of political, social, and economic thought, has provided the clearest and most comprehensive lens for analyzing society and charting a path toward its transformation. Marxism is not a set of final conclusions, but instead a method that tries to understand the contradictions out of real movement history and the process of class struggle.

At the core of Marxism lies a materialist worldview—one that integrates history, science, and collective memory into a framework for understanding societal change. Emerging from the class struggles of the 19th century, the materialism at the base of Marxism is not just a philosophy but a tool of liberation, rooted in the rise of the proletariat. When Marxism is described as an ‘applied science,’ it refers to its method: analyzing how material conditions shape society and exposing the inherent contradictions of capitalism—particularly the escalating conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, which reflects the historical unfolding of these contradictions. The basis of this method of scientific analysis lies in historical materialism, which has four basic rules: (1) all phenomena in the material world are linked to each other: everything has a cause and effect, and is a cause and effect; (2) reality is dynamic and all things come and go: the world is in constant motion and we must see things as being part of a process and as having a history; (3) historical change happens in qualitative leaps that are influenced by quantitative shifts in conditions: ‘progress’ is not linear and ruptures with existing systems are required for revolutionary change; and (4) the dialectic of contradictions is the driver of historical processes: there is a positive and negative aspect to everything.

Historical materialism, then, helps us to understand the various dimensions of exploitation, injustice, and oppression in our world, so that we might change it. Exploitation is not some occasional or accidental feature of capitalism—it is the very foundation of the system. Under capitalism, this exploitation is concealed by the wage system: capitalists purchase workers’ labor power for a set period, and in return, workers receive wages that superficially appear as fair compensation. However, this exchange is far from equal. While workers generate vast amounts of wealth, the lion’s share flows to capitalists, who already possess disproportionate economic power. Wages are set only at the level needed to sustain workers’ basic survival—covering food, clothing, housing, and just enough education to maintain their exploitable labor power—while the surplus value they produce is appropriated by capital.

The value of labor power is determined as in the case of every other commodity by the labor time necessary for the production, and consequently also the reproduction, of this special article. So far as it has value, it represents no more than a definite quantity of the average labor of society incorporated into it. – Karl Marx, Capital vol. 1

Marxism should not be reduced to anti- capitalism, however. For Marxism, the key to understanding historical processes lies in how human beings produce their material means of life. The materialist conception of history begins with a fundamental premise: the production and exchange of goods form the foundation of all social structures in every society. Throughout history, the distribution of wealth and the division of society into classes have been determined by what is produced, how it is produced, and how those products are exchanged.

Idealism, in contrast, asserts that ideas, beliefs, and consciousness are the primary forces driving historical development—treating shifts in material conditions, such as economic structures or technological progress, as mere byproducts of evolving thought. Material conditions, according to Marx, refer to the economic and social factors that shape human society and influence its development.

Materialist dialectics, however, emphasizes the importance of material conditions, referring to the economic and social factors that shape human society and influence its development, and the contradictions within social relations, recognizing that change is constant but never occurs independently of human intervention. It is precisely through our deepening understanding of nature and society that we gain the ability to consciously guide the process of change.

But what does Marxism as a liberatory philosophy mean for guiding us towards creating conditions for a revolutionary capture? What does Marxism have to do with the African?

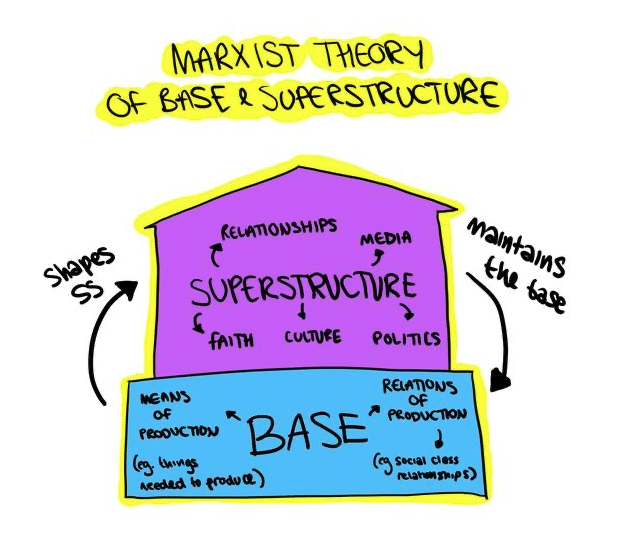

Marx’s Base and Superstructure theory holds vast and critical implications for revolutionary organizing. The base—means of production (factories, land, machinery, etc.) and the relations of production (wage labor, private property, class antagonisms)—forms the material foundation of society. The superstructure (culture, ideology, media, religion, etc.) arises from and reinforces this base but does not drive historical change independently. Too often, well-intentioned efforts focus on combating superstructural symptoms (racist ideologies) while neglecting their economic roots. For Marxists, transformative struggle must target the base—the site of capitalism’s fundamental contradictions.

Take white supremacy: its superstructural expressions (race ‘science,’ fascist politics, reactionary ideologies) did not precede chattel slavery. Rather, they emerged to justify an already profitable system of enslaved African labor—a base-level exploitation. This historical materialist analysis underscores why collective memory is indispensable for Marxism. For Africans in particular, reclaiming our history is revolutionary: its erasure obscures the base’s role in shaping oppression, while its recovery arms us with the knowledge needed to dismantle it.

Scientific socialism, as a method of analysis, reveals how capitalism alienates African labor while extracting surplus value from it. For Africans (especially in the U.S.) whose labor has been historically exploited under racial subjugation by way of capitalism, Marxism provides a lens to understand their relationship to production, class struggle, and systemic oppression. Marxism’s universality speaks directly to the material conditions of African workers in the U.S., who remain disproportionately marginalized in the labor market, facing wage theft, underemployment, and hyper-exploitation in industries from prisons to service work. Marxism is not an imposition but a logical tool for African liberation, one already validated by struggles of non- European peoples who have wielded it to dismantle colonialism and build socialist societies.

African people in the U.S., whose exploited labor has been a cornerstone of capitalism, must engage with Marxism not as an abstract theory but as a necessary tool for liberation. Dialectical materialism teaches that material conditions—such as wages, workplace exploitation, and racialized dispossession—shape consciousness, but without a revolutionary movement, isolated changes (like minor policy reforms or corporate diversity initiatives) fail to dismantle the base of capitalist oppression. History shows that concessions granted under pressure—from Reconstruction-era land redistribution to Civil Rights legislation—are often rolled back when they threaten ruling-class power. This is because reforms that don’t transform the economic base (the system of ownership and production) leave the superstructure (laws, culture, ideology) intact, allowing racial capitalism to absorb and neutralize dissent. For Black workers, this means understanding that higher wages or better working conditions, while necessary, are insufficient if the system extracting their labor remains unchallenged. We cannot substitute a foundational historical understanding that serves as the basis of collective unity with piecemeal reforms that we hope will ‘accumulate’ over time. Taking that qualitative leap toward revolutionary change requires addressing exploitation at its base.

History teaches us that in certain circumstances it is very easy for the foreigner to impose his domination on a people. But it also teaches us that, whatever may be the material aspects of domination, it can be maintained only by the permanent, organized repression of cultural life of the people concerned. Implementation of foreign domination can be assured only by physical liquidation of a significant part of dominated population. – Amilcar Cabral, National Liberation and Culture.

A principle characteristic of imperialism is its systematic erasure of the historical development of oppressed peoples—achieved through the violent usurping of the free operation of the process of development of productive forces.. Before national liberation movements emerge politically, they manifest culturally, as the dominated people reclaim their identity to resist the colonizer’s imposed culture. This cultural assertion (collective historical memory) becomes the seed of opposition, preceding organized struggle.

National liberation is, fundamentally, an act of cultural reclamation—a declaration that every people has the inalienable right to their own history and self-determination. Culture is not an abstract or static phenomenon; it is shaped by material conditions and, in turn, shapes them. As Fanon, Nkrumah, and Cabral all elucidated, a revolutionary national culture emerges through the process of anti-colonial resistance and is rooted in, but not limited to, the historic traditions, practices, and socioeconomic conditions of a people. Culture, then, is a key terrain of struggle. For Marxists, since culture is rooted in the modes of production (the base), transforming these material conditions is essential for true liberation. Revolutionary change, therefore, demands both cultural and economic transformation.

Collective historical memory shows us, as evidenced in much of Rodney’s work, Marxism is not bound by geography or race but is a universal framework for analyzing and transforming material conditions. A revolutionary Marxist approach insists that African liberation requires not just changing material conditions but overthrowing the structures that reproduce them. The superstructure—white supremacy, carceral policing, and ideological narratives of African inferiority—reinforces the economic base, ensuring African labor remains exploitable. Without a movement that connects workplace struggles to the broader fight against capitalism, reforms will remain fragile and reversible. The rollback of affirmative action, the erosion of labor rights, and the persistence of racialized wealth gaps prove that partial gains are easily undone. Marxism, as a methodology, equips African workers to see their struggles as part of a global class war, linking our fight to anti-colonial movements that have wielded dialectical materialism to dismantle imperialism.