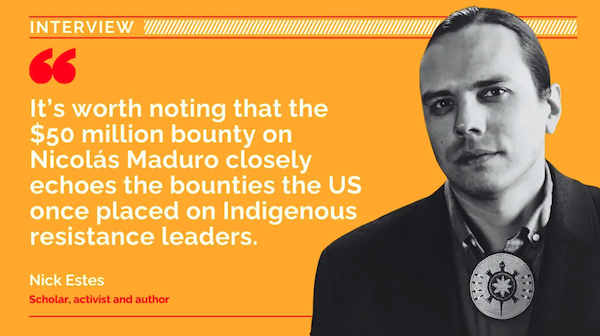

An enrolled member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, well-known historian Nick Estes co-hosts The Red Nation podcast. He is the author of Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Verso, 2019), a book that situates the struggle against the pipeline in the context of centuries of Indigenous resistance to U.S. colonialism and imperialism.

In this interview, Estes traces the continuities between U.S. settler colonialism and imperial projects abroad, highlighting how the so-called Indian Wars provide the template for Washington’s forever wars. He also discusses how the United States has targeted both Indigenous peoples within its own territory and countries like Venezuela through dispossession, war, and sanctions.

Estes’ perspective underscores both the depth of U.S. imperialist violence and the urgent need to forge links among Indigenous, anti-imperialist, and Bolivarian and Latin American struggles.

Cira Pascual Marquina: It’s well known how U.S. imperialism is violent and even exterminist toward people and nations abroad, with the genocide it is carrying out in Palestine and the unilateral coercive measures it directs at Venezuela being clear examples. However, imperialism is also rooted in internal colonialism, particularly the dispossession of Indigenous nations in North America. How do the imperialist processes inside the U.S. mirror those that take place outside?

Nick Estes: In our hemisphere, two key ideologies underpin U.S. colonialism and imperialism: Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine is essentially an extension of Manifest Destiny.

When the United States was founded 250 years ago, it consisted of just 13 colonies along the eastern seaboard. Within a century, it had expanded to seize more than a billion acres of territory and overseas possessions. This expansion advanced the project of a white supremacist nation at the expense of Indigenous peoples. The Monroe Doctrine extended that same logic to the entire hemisphere.

We can see this doctrine scaled up to the global stage today, with Palestine as the most extreme example. What is the point of such violence? It’s partly terror—sending a message to the world: this is what happens if you resist Empire; this is what you can expect if you try to build sovereignty and liberation.

Israel, a Zionist project, also serves U.S. interests by projecting power in West Asia, destabilizing regional sovereignty, and ultimately opening a “back door” to China. This is closely tied to the Trump administration’s agenda: tariff wars, targeting China’s neighbors, and controlling the resources necessary for new technologies. None of this is hidden: it is openly stated.

Finally, the wars in West Asia are also warnings to this hemisphere.

The Monroe Doctrine has meant coups and interventions across Latin America. Recently in Venezuela, it has expressed itself in devastating sanctions and gangster-style regime change attempts, including a $50 million bounty on Nicolás Maduro. It’s worth noting that this “bounty” closely echoes the bounties the U.S. once placed on Indigenous resistance leaders. In short, today’s attacks on Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua are continuations of the wars once waged against Indigenous nations in what is now the United States.

When the ink on the Constitution was still wet, George Washington led a bloody war against the Northwest Confederacy of Indigenous nations. This marked the beginning of more than a century of so-called Indian Wars: fourteen major conflicts marked by genocide and dispossession. The effects are still felt today.

The U.S. uses these wars as a precedent for its current “forever wars.” For instance, when it bombed Iran’s nuclear facilities, Trump did so under the same authority of the first president, George Washington, who waged war in 1790 against Indigenous nations without formally declaring war or seeking congressional approval. Following World War II, this logic was extended to wars in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and beyond. In this way, the so-called Indian Wars became a model for permanent global warfare.

CPM: Both in North and South America, colonialism morphed into imperialism. We share a history of dispossession. Do you see this shared past—and our present struggles—as bringing our peoples closer together? I raise this question because Indigenous movements in the U.S. fight for land, sovereignty, and self-determination, and these are also central pillars of the Bolivarian Revolution.

NE: I’d like to answer with recent history. In the U.S., Indigenous people are racialized through erasure. We’re often seen as historical relics rather than as living, political communities—colonialism still shapes our daily reality. In South Dakota, where I’m from, Indigenous life expectancy is just 59 years, nearly two decades lower than that of white people.

So yes, we struggle for land, sovereignty, and self-determination, which aren’t abstract ideas for us. They are tangible because they increase our life chances.

Half a century ago, the Red Power movement went international, building relationships with Nicaragua, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and other revolutionary organizations around the world. More recently, in 2007, Vernon Belcourt, a leader of the American Indian Movement, visited Chávez to establish a Citgo program that provided heating assistance to tribal nations. My tribe benefited from that program—that was how I first learned about Comandante Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution.

A few years later, at Standing Rock, when people asked why we were resisting the Dakota Access Pipeline, activist Winona LaDuke explained that our struggle against the pipeline was also a rejection of U.S. sanctions on Venezuela, the country with the world’s largest oil reserves. In other words, the pipeline—designed to transport some of the dirtiest oil in the world—was directly tied to the Empire’s goal of crushing Venezuela. Internationalist connections were being made in the midst of the struggle. Local media couldn’t grasp this, but Indigenous movements there knew the struggles were linked.

Within the U.S., we also face an internal struggle. Tribal sovereignty can be aligned either with imperialism—sometimes through reactionary currents tied to Trump—or with anti-imperialism and solidarity with the struggles of oppressed peoples around the world. History shows that aligning with imperialism has always been disastrous for Indigenous peoples.

Hugo Chávez and a Pemón person. The Bolivarian Constitution represents a before and an after for Indigenous people. However, there are still pending tasks. (Photo: Prensa Latina)

CPM: In 2019, you visited Venezuela with a delegation of young Indigenous people from the U.S. You visited again in 2020 and 2021. Can you share some of your experiences?

NE: When I visited Bolívar state [southern Venezuela], I was very taken by the resilience of the Indigenous communities, specifically the Pemón community, which identified openly and explicitly as Chavista, saying they are part of the revolutionary project.

Some of the people I spoke with had received formal training as community healthcare specialists, combining their Indigenous knowledge of healing and medicine with Western science. The Constitution allows this, promoting protection for traditional practices all the way up to the level of political participation.

In Indigenous communities, people often vote by consensus and, in some instances, without a secret ballot, thus maintaining their core assembly-based practices. These are constitutional protections that we, as Native people in the United States, simply don’t have.

Additionally, the Venezuelan Constitution not only safeguards these practices but also guarantees Indigenous representation in the National Assembly. By contrast, Indigenous peoples in the U.S. have no guaranteed representation in Congress and lack constitutional protections like those in Venezuela. We are often told that things are better in the U.S., but constitutionally and politically, Indigenous peoples in Venezuela are far more integrated into the national project.

Of course, Venezuela’s process is not perfect: there is an ongoing struggle and persistent demands for legal and constitutional reforms, which I understand may be coming soon. However, sanctions directly undermine these efforts. If we are committed internationalists, the first step is to work toward lifting sanctions, allowing Indigenous peoples and all Venezuelans to pursue self-determination within the Bolivarian framework.

CPM: We’ve seen moments of reciprocal solidarity: Chávez’s heating program for tribal nations and Standing Rock’s recognition of the harm the U.S. inflicts on Venezuela are just two instances. Yet, building deeper, ongoing connections remains an unfinished task. Since the Venezuelan communal project draws from Indigenous traditions, and Indigenous peoples in the U.S. continue to struggle to advance community-building efforts, the question becomes: How can we strengthen these ties?

NE: In North America, even within Indigenous movements, there’s sometimes hesitancy to connect with international struggles. Liberal environmentalists, for instance, often try to silence these connections. But we have every right to build relationships with movements around the world, just as the American Indian movement did in the late 60s and 70s.

When I visited the Kaika Shi community in Caracas, a matriarch told us, “The first enemy is the capitalist in your head. Don’t wait for someone else to solve your problems, you must solve them here and now!” Her words deeply resonated with the Indigenous youth traveling with me. In the U.S., we often suffer from “program-itis”—programs for everything, yet crises of addiction, suicide, and poverty persist. Programs alone don’t dismantle colonialism. Self-determination does.

Delegations like ours are crucial. It’s hard for Venezuelans to travel to the U.S., but exchanges are necessary. Too often, Indigenous peoples in the United States internalize chauvinism and dismiss other struggles. But when they meet Venezuelan, Bolivian, or Cuban comrades face-to-face, they see the connections immediately.

I remember one youth delegate telling me something that was deeply meaningful: “Venezuela is one big reservation.” They meant two things: first, that Venezuela is besieged by the US; second, that, like a reservation, Venezuela has a communal spirit where everyone knows each other and struggles together.

This is something you can only truly understand by meeting people who are actively building the world we all want. Venezuelans never told us: “copy our model.” Instead, they always said:

Make your revolution at home. Build dignity among your people first, while aligning with the Bolivarian Process.

Kaika Shi in Caracas. Below, Indigenous youth delegation in Kaika Shi. (Photo: Nick Estes and archives)