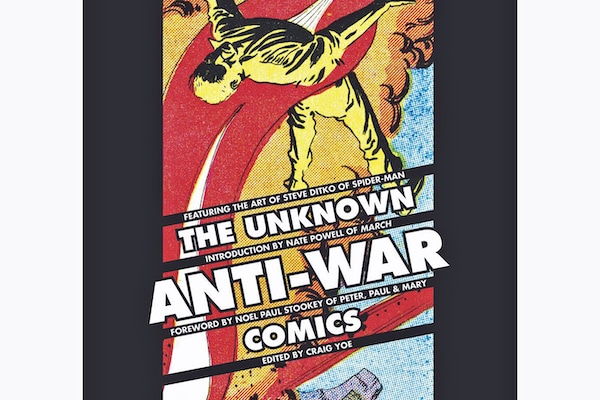

The Unknown Anti-War Comics. Edited by Craig Yoe. San Diego: IDW Books, 2018. 233pp, $29.99.

Who knew? Not me, an assiduous fan of dissenting, social-critical, antiwar and antiracist comic art since at least the first issue of Mad Comics that passed under my eyes in summer of 1955 (I was not quite 11). The most marvelous age of comics popularity, creativity and political diversity was passing, not only thanks to the growing universality of television (still spreading then, from the coasts inland) but also to the reign of censorship, actually self-censorship, that drove out nearly all the most daring comics. The next phase of rebellious art, I have thought all this time, belonged to the rise of the Underground Comix of the later 1960s, with one tip of the hat to the campus satire magazines that in some places gave artists like Austin’s Gilbert Shelton a start, and another to Harvey Kurtzman’s failed magazines after Mad, especially Help! (1961-65).

No, I was wrong, and I am happy to discover something hidden in the interstices of the troubled pulp trade. One of the lesser lights of comics production, Charlton, offered a handful of artists and scriptwriters the opportunity to make a statement about the threat of nuclear war, a frequent subject in EC Comics’ science fiction series early in the 1950s. EC, the company that spawned Mad Comics and Mad Magazine, had earned bread-and-butter from gory horror comics and some very noir-ish titles of crime and molls with prominent curves beneath tight sweaters. But exploitation made possible the most realistic war comics, actually anti-war comics, of the time, and a Sci-Fi line that looked suspiciously like Ray Bradbury stories and once cleverly sent them a bill for one that they adapted without telling him! (They paid and began adapting more.) At any rate, such plots often led survivors to come across destroyed cities and realize that a Great War had brought down all civilization.

Comic books survived with kid stuff like Little Lulu and Casper the Friendly Ghost, the Ducks, and more important in the long run, the new or revived superheroes from the 1940s now seen, generations later, on the big screen.

What happened to antiwar themes? Not much at all. Are more than a few superheroes on the screen or in the surviving comics antiracist, gay or gay-tolerant, not to mention neurosis-ridden? For sure. Spectacles, nevertheless, demand violence, the more spectacular the better. But we digress.

The Unknown Anti-War Comics brings us back to a remarkable remnant. In the Preface, Noel Paul Stookey (Paul of Peter, Paul and Mary) recalls sitting with his dad listening to a radio report of the Atom Bomb test in 1945, and a few months later sharing joy at the American victory over Japan. Some decades later, on stage, he became a famed antiwar warrior, so to speak, and perhaps for that reason, is able to identify the leading principle in this book in the key motive of the stories’ heroes: love. That is, they had enough love to say “No” to the many opportunities to pull the trigger and bring the massive casualties that technology makes possible.

Editor Yoe follows with a detailed, erudite essay on war comic lines including children warriors (he calls them the “saddest”) and the toy weaponry merchandise offered in the back pages that we comics readers from those times remember so vividly. As he observes, the most vivid antiwar comics did not emerge until the second half of the 1950s, when the short-lived Never Again comics appeared, in sometimes unpublished work from defunct comic companies—a marker of how near the bottom of the trade the peace comics were.

“Never Again” was already becoming a theme linked to the Holocaust, but had been earlier adopted during the 1920s-30s mass disillusionment with the First World War, and exposure of the “merchants of death,” the American companies that had devilishly promoted U.S. entry into the War in 1917. When a WWII vet, Joe Gill, linked up with Charlton co-owner John Santangelo (who had served time for copyright violations but would become a noted supporter of the United Nations), a new possibility took shape. Borrowing President Eisenhower’s warning against future wars, the two mini-moguls found comic artists who worked cheap and could deliver the message: the doom that lay ahead in future war-making.

Mostly, in these pages, the stories recall the EC Sci-Fi themes, space cadets seeking to contact a civilization-destroyed planet earth. Sometimes they only need to go a few decades ahead to come across aliens warning against the earthlings’ race toward doom. Sometimes we go backward in time to the Hundred Years War in Europe, forward through the famed air battles of the First World War. Some of the strips are drawn by Steve Ditko, co-creator and lead artist of Spider-Man, more often by forgotten artists of more limited talent.

No matter. Dig in, reader, and see if you can find a kid who wants to read comics and doesn’t mind the antique quality of the mid-century comic art. There are treasures here.