Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Last week, Agence France-Presse got its hands on a draft UN report called Special Report on the Ocean and Cyrosphere in a Changing Climate. This 900-page document is study of the oceans for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body which won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2007. What extracts have become available make for chilling reading. ‘The same oceans that nourished human evolution’, the draft says, ‘are poised to unleash misery on a global scale unless the carbon pollution destabilising Earth’s marine environment is brought to heel’.

Unless there are deep cuts to the carbon emissions created by humans, at least 30% of the northern hemisphere’s surface permafrost could melt within the next eight decades. This would mean that by 2050 the oceans will rise, and the ‘extreme sea level events’ will wipe out islands and low-lying megacities. Few scientists are convinced that warming can be controlled at the threshold of 1.5˚C; they hope for 2˚C. At this increase of temperature, the oceans will rise sufficiently to displace more than a quarter of a billion people; these displaced people–at 250 million–would collectively form the fifth largest country in the world after China, India, the United States of America, and Indonesia.

The final Special Report on the Ocean is to be released on 25 September, two days after a special Climate Action Summit hosted by the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in New York. In late August, Guterres spoke at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development, where he noted, ‘Little undermines development like disaster’. He had in mind the terrible cyclone Idai that struck Mozambique, destroying 90% of the area around the city of Beira. Watching this drone footage again from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies is chilling.

IFRC drone footage of Cyclone Idai in Beira, Mozambique, 2019

Disasters are not hard to find. Hurricane Dorian has swept through the Caribbean with ferocity. Guterres mentioned the fires in the Amazon, a crime against humanity–as the peasant organisation La Via Campesina put it. It is disturbing to watch this short video–Brazil in Flames–made by Brasil de Fato:

‘Decades of sustainable development gains can be wiped out overnight’, Guterres said about these cascading disasters. And there will be more such disasters. ‘We are on track’, Guterres said, ‘for 2015-2019 to be the five hottest years since there are records’. The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) says that we now have the largest concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere in world history. As far as oceans are concerned, the WMO shows that Ocean Heat Content in the upper 700m and the upper 2000m in 2018 were ‘either the highest or second highest on record’.

Culpability is of different levels. Both Mozambique and Brazil face the deleterious impact of the climate catastrophe, but in the case of Brazil there is also a more proximate culprit–the logging and mining firms. When it comes to pointing fingers, one or two hands are not enough. Fingers must point toward the conglomerates of finance and energy that make their money from carbon. They would also point with intensity at the countries in the G-7 and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development that refuse to bargain in good faith at the climate negotiations.

The fingers would be remiss if they did not point with special ferocity at the two-faced behaviour of the developed countries. Professor T. Jayaraman of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Mumbai) told UNESCO’s Courier that the talk of carbon taxes and carbon trading is a smokescreen. Why don’t these governments simply ‘mandate certain targets to be reached by certain industries? There have to be tighter regulations. Otherwise they should be made to pay the penalty’. ‘To believe that you can sweet-talk businesses into acting morally, or scare them into taking the right steps, seems to me a little absurd’, Jayaraman said. Developed countries, he said, need to ‘convert rapidly to green technologies’, which does not mean to just change fossil fuels (gas for coal) but which means to transfer to renewable energy. On the other side, developing countries must leapfrog, but in a sensible way. Public transport in the Chinese city of Shenzhen, for instance, is all electric–with the plan to make all transport in the city follow suit.

South China Morning Post, Shenzen: the World’s Pioneer in Electric Vehicles, 2018

Agung Mangu Putra, Abstraki Ikan, 2001.

Prevarication on the climate catastrophe is merely the same evasiveness that emerges when capitalism confronts the moral questions of hunger and homelessness, indignity and inequality. There are charming theories that allow the capitalist class to keep appropriating almost all social wealth, while the workers and peasants live at the edge of survival. It is not the lack of motion to confront the reality of the climate catastrophe that is the problem; it is the affliction of affluenza, the deep cultural roots of capitalism, that will prevent a solution to both social and climate catastrophe.

Answers are given for symptoms, not for causes. The waters rise, so Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital, builds a 24-meter-high sea wall even as 40% of the city is already below sea level. Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo knows this is no solution. He has announced that the fourth largest country in the world will move its capital to the island of Borneo. Meanwhile, the UN has held a preliminary discussion on a new agreement on the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea to conserve and sustain marine biological diversity. Everything seems timid–the Voluntary Trust Fund is merely to offer finances so that small island states can come to these meetings. Nothing else is on the table. There is no real commitment to tackle sea rise or ocean acidification. Tuvalu’s Fakasoa Tealei said that the existing frameworks are ‘ineffective’ and even this discussion might not add ‘any practical value’ to the problem. Tealei’s honesty and Widodo’s surrender to the sea are disappointed canaries in an endless coal shaft.

Tonga, the archipelago south of Tuvalu in the Pacific Ocean, is vulnerable to being washed away in the rising waters. Tonga’s main islands have built sea walls, but their residents can look across the waters and see their smaller islands slip into the ocean. Where would the 100,000 Tongans go if the waters rise? Konai Helu Thaman, one of Tonga’s great poets, wrote decades ago of her dream of another world.

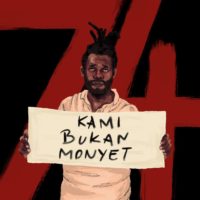

Ivana Kurniawati, We Are Not Monkeys, 2019.

We cannot see

far into the distance

neither can we see

what used to stand there

but today we can see trees

separated by wind and air

and if we dare to look

beneath the soil

we will find roots reaching out

for each other

and in their silent inter-twining

create the hidden landscape

of the future.

North-east of Tonga is West Papua, the half of the Papua island that is held by Indonesia. Strong feelings for independence stir once more in West Papua after Papuan students were treated disgracefully by Indonesian nationalists in the town of Surabaya. Called ‘monkeys’ by these nationalists, the Papuan radicals reversed the order of things: Papua merdeka, itu yang monyet inginkan (Free Papua, this is what the monkeys want). One of the leaders of the struggle–Surya Anta–has been arrested. The situation is very unclear, with internet to West Papua closed. In a future newsletter, we will run an interview with Benny Wenda of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua.

One of the lingering residues of the independence struggles in South America has been the question of continental integration. This comes up regularly, most recently during the Pink Tide. Then the question of integration emerged as a part of the regional class struggle–should the terms of integration merely benefit the oligarchy and multi-national firms, or was integration a means to socialist development? Last week, in Rio, as part of a Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research co-organised series, Monica Bruckmann and Beatriz Bisso of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro joined Mariana Vazquez of the University of Buenos Aires and Olivia Carolino of Tricontinental before a crowded room of academics, students, and militant to discuss these themes. The idea of integration is a pressing one, but not integration without a clear assessment of its class character. Globalisation is a form of capitalist integration; integration of countries on a programme to benefit the working-class and peasantry is an entirely different issue. How to do it when the balance of forces is adverse? That’s the question on the table. These presentations will be folded into a book from us.

It has been ten years since Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez address the climate conference in Copenhagen. Chávez evoked the regionalism of Latin America–notably ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the People of Our Americas). His sharpest comments came when he pointed his finger at the richest individuals and countries of the world whose attitude ‘shows high insensitivity and lack of solidarity with the poor, the hungry, and the most vulnerable to disease, to natural disasters’. The richest, Chávez said, should do two related things: first, ‘set binding, clear, and concrete commitments for the substantial reduction of their emissions’; and second, ‘assume obligations of financial and technological assistance to poor countries to cope with the destructive dangers of climate change’. Simple.

Chávez saw those roots reaching for each other. But this is not a perspective shared by the G7 and the OECD. They see the fruits, which they want to pluck and eat for themselves. That’s their attitude. It is the attitude of the marauder, not of the human being.

Warmly, Vijay

PS: all our materials are available at our website, including all newsletters and dossiers, working documents and notebooks, briefings and red alerts. If you have questions, please reach out to our offices in Buenos Aires, Johannesburg, New Delhi, and São Paulo.