Mainstream American media outlets typically portray female massage parlor workers — many of them immigrants from Korea, Vietnam, and in recent years, China — as victims of transnational crime syndicates. But when I mentioned that stereotype to Lily, a Chinese massage parlor worker in Seattle’s Chinatown, she erupted. “What a bunch of dogs—!” she fumed. “They have no idea what they’re talking about. Do they think Chinese people all live in the Dark Ages?”

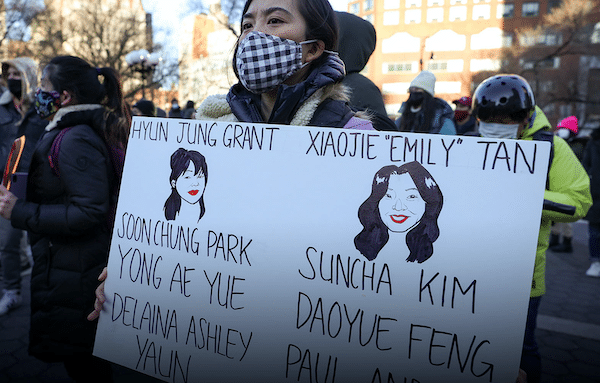

The recent mass shooting in the city of Atlanta, which left eight people dead, six of them women of Asian descent, has reverberated throughout the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) community and sparked protests across the country. It has also dragged the women who staff America’s massage parlors back into the spotlight, often in ways that only further stigmatize them and their profession.

Of course, none of this is new. The violence perpetuated against the AAPI population — especially middle- or lower-class immigrants — didn’t start with the pandemic. The Asian women who work in America’s massage parlors have long been subjected to systemic violence that the rest of society would prefer to ignore: Even the recent protests against anti-Asian violence have preferred to dance around the subject. Yet we cannot truly comprehend the roots of this violence until we learn to recognize these women and understand their experiences.

Lily immigrated to the U.S. six years ago and splits her time between Washington and California, both states with large Chinese communities. A single mother, she spent two decades working as a white-collar professional in China. Eventually, she realized that her income, which had remained stagnant for much of that time, was being overtaken by surging housing and commodity costs even in China’s smaller cities. After her only son went off to college in 2015, she flew to the U.S. on a tourist visa to, in her words, “go gold-digging.” Her goal was to find a way to pay for his tuition and save up for a down payment on a house for him.

Another Seattle-based massage parlor worker, Xixi, took her daughter with her to the U.S. and left her husband behind in China. While her daughter attended language classes to prepare for college, Xixi searched for work opportunities in the local Chinese community. After interviewing at various companies, she discovered — as Lily and many other Chinese immigrants had before her — that her inability to speak English meant even some Chinese restaurants and grocery stores weren’t interested in hiring her.

Even if she had landed one of these jobs, the workloads were intense, the bosses casually cruel, and the pay low. Women like Lily and Xixi, who have worked for decades as skilled employees back in China, often struggle to adapt to such conditions.

Some instead decide to enroll in a training course at a Chinese-language massage therapy school before taking a job at one of the growing number of Chinese-owned massage parlors. Finding work at those parlors isn’t too hard, even for those with poor English skills, because interactions with customers tend to follow the same rote scripts. In this way, massage parlors have become a safe harbor for middle-aged Asian immigrants who don’t have the heart to master a new language.

Many massage parlor workers say they earn more and enjoy more freedom than at other jobs. Although the parlors’ hours are long — 12 hours a day, six days a week is the norm — employees are only busy when customers are around. In their down time, they can watch TV or video-chat with friends and family back home on their iPads or phones. On top of that, the massage parlor owners are rarely on-site, giving them even more space.

However, this freedom also brings risks. Chinese massage parlors have always been an easy target for robberies, but this is especially true since the pandemic began: As business fell to a third or a quarter of its usual numbers, many owners chose to downsize their staff, leaving only one worker to run the entire parlor. This made them even more vulnerable.

Some massage parlor workers and owners might try going to the police for protection, but most stay silent. “The police are absolutely useless. Reporting an incident to them is just a waste of time,” Chang informed me. A proud woman with a thick Northeast China accent, Chang was laid off from her managerial job at a large state-owned company about 20 years ago. She spent years adrift in a difficult job market, especially for middle-aged women, before rolling the dice and emigrating to the United States. Now in her 50s, the massage parlor where she works has been robbed on multiple occasions, but every time she calls the police, she feels like they’re bullying her.

Indeed, many of the massage parlor workers I’ve spoken with distrust law enforcement, saying the police look down on parlor workers as human trafficking victims, undocumented immigrants, illegal sex workers, or just ignorant Asians with limited English: at any rate, certainly not “decent citizens” worthy of their protection.

Some massage parlor workers do provide various sexual services ranging from body rubs to hand jobs and penetrative sex. But that’s not true of everyone, and regardless, no one should need to prove that they have no relation to sex work to qualify for protection from violence or mistreatment.

Instead, after former U.S. President Donald Trump signed the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act in 2018, police forces renewed their efforts to crack down on the industry. Raiding massage parlors in major Chinatowns across the nation, they detained — or to use the police’s preferred term, “rescued” — over 200 Chinese.

In Seattle, the police raided 11 massage parlors and “rescued” 26 Chinese women from a “sex-trafficking” ring, according to media reports that uncritically quoted local law enforcement. The claims made headlines, but they were misleading: Nobody was indicted for trafficking. The owners were charged with promoting prostitution and money laundering, then fined and released on probation. Their “rescued” female employees, on the other hand, lost both their jobs and their housing, which was connected to their workplace. Many also had their meager cash savings and other belongings confiscated.

This same story has played out, over and over, for decades, and every time it further stigmatizes, demonizes, and victimizes female massage parlor workers of Asian descent. Far from “rescuing” these women, it’s actually made their lives more dangerous. The situation goes beyond the simple fact that the more massage parlor workers are forced to depend on their employers for protection, the harder it is for them to resist labor exploitation: These narratives form part of the web of individual and structural violence that allowed Robert Aaron Long to shoot up three Asian massage parlors and take eight lives last month.

The day after the shooting, eight volunteers from our aid organization fanned out to visit 12 massage parlors in Seattle’s Chinatown. (A fraction of the number prior to the police raids in 2019.) The most common responses we heard were “I’m scared,” “It is what it is,” and “We’ll be locking up earlier at night.”

Lily was a bit more forthcoming. She talked to us for 20 minutes about the social causes of “violence directed at AAPI,” as well as her disappointment with the “American dream” and American democracy six years after her arrival in the United States. She also spoke candidly about her anger at the Asian immigrants who had climbed their way into the middle class, then “turned around and kicked those of us still in the dirt.” As for the political and economic structure of the U.S., she bluntly stated that “white supremacy and national policy are colluding” to oppress laborers of color struggling to survive.

I’m sharing her wisdom because the attack in Atlanta was about more than just a solitary killer and his racial prejudices; it reflects widespread discrimination and inequalities that for too long have gone unchecked in American social structures and institutions. Even now, many of us in the AAPI community are emphasizing that we’re legal and law-abiding citizens, that we deserve to be protected. But why should anyone be excluded from these protections? Shouldn’t we also be asking if the laws, institutions, and law enforcement officers we’re appealing to are truly fair and just? Is more policing really the answer? For many of the most vulnerable members of our community, the answer seems to be no.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.