With the onset of the pandemic, the second Black Lives Matter movement, and the economic crisis, theatre as an art form and an industry is in a period of crisis and rebuilding. This is doubly true of political theatre, which explicitly intends to dialogue with the current political moment. Artists who pride themselves on creating politically minded art are assessing their own role in the system of racism, oppression, and exploitation that we live under, and many are wondering what the path forward is. Whatever anyone believes and wherever anyone stands, the truism is that theatre cannot go back to the way it was before the pandemic, because both the world and the way people engage with it have fundamentally changed.

For years, political theatre has largely been reduced to simply calling out the problems in society, leading to a glut of plays that simply tell their (usually white, upper middle class, liberal) audiences that racism/sexism/homophobia/etc. is bad. Plays are presented either as world premieres in major metropolitan centers or as toothless revivals in regional houses that are, in essence, two-act sermons to the choir. This creates a political theatre that only challenges the ideas of those who, by and large, will never see the plays and allows those who will see the plays to pat themselves on the back for how progressive they are.

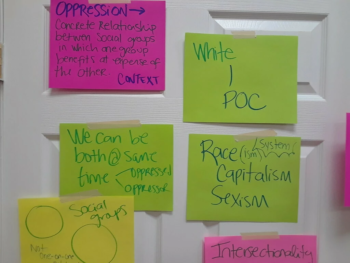

Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed provides theatre techniques for “regular” people to learn to recognize and resist oppression. “Theatre of the Oppressed” by National Farm Worker Ministry is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

This is not simply the by-product of lazy artists but, rather, of the increasingly difficult economic realities of creating theatre. The systematic governmental defunding of the arts since the days of Reagan has led most theatre companies to rely on corporate and private donors. Because theatre artists rely on those with power and money for a platform, they are effectively forced to create relatively unconfrontational political art, where the trick is to appear political (typically through representation in the stories, as if simply saying that people of color/queer people exist is tantamount to making a political statement) without actually putting forward a political perspective that challenges the powerful and privileged people seeing the plays. This has led to an increasingly irrelevant political theatre that is totally ill-equipped for life after COVID.

The nature of political theatre is to be disruptive. This principle has guided every major political artist but is quickly being forgotten due to the current nature of the theatre industry. When political theatre preaches to the choir, it removes its potential to disrupt. Indeed, by having such a laser focus on bringing “awareness” to issues, much political art forgets to have a point of view. Art in the current landscape tells us that we live in a racist society or that violence against women exists, but it doesn’t tell us how to fight back. So, we’ve left behind activist theatre and are now engaging in an empty journalistic theatre.

This style has been irrelevant for several years, but it has never been more so than in the current moment. We watched George Floyd’s murder; we don’t need to sit in a theatre and be told that police violence against Black people exists. We watched the government fail to protect the vulnerable during the pandemic; we don’t need to sit in a theatre and be told that the government is corrupt. We don’t need art to just raise awareness, we need art to give us a way forward. This is impossible without radically changing both the aesthetics and expectations of political art.

If we look at the greats of political theatre, such as Augusto Boal—the founder of Theatre of the Oppressed, a practice that uses theatrical techniques to give people tools for recognizing and resisting oppression—and Bertolt Brecht—a Marxist poet and playwright who used his plays to critique the established order of the day and called on his audience to enact change—we can see how they applied a more coherent political perspective to their work, which helped them cut through the noise and disrupt the established order. Brecht, as I’ve written about previously, put forward an aesthetic for political art that we’ve moved away from. This aesthetic is not just an artistic one but a political one. It is drawn primarily from his reading of the political theory of Karl Marx. Indeed, Brecht once remarked that it was only after reading Marx’s Capital that he finally understood his own plays.

In the decades since the end of World War II, we have seen a de-Marxing of art. Since the McCarthy era purges, activist-artists who use their art to paint a picture of how the world could be and/or rile people up to change it, which was so common in the thirties, has steadily been disappearing. In addition, expectations for political art have changed. We no longer expect art to give us hope, solidarity, and a fighting spirit, but instead to showcase our struggles. We see beautiful and moving plays that show suffering in communities without offering a perspective on how this pain could have been alleviated through political means. In other words, these plays collapse this suffering to being individual and cosmic, rather than the structural result of political policy. An increasingly passive “political” art has emerged that tells the “good” members of the ruling class—the “cultured” and “progressive” sector who attend the theatre—that as long as they know people are oppressed, they don’t have to change anything about the way they live their lives.

But I believe the goal of political theatre must be to disrupt and to put the struggles of the current moment into a political perspective. In the words of twentieth-century political folk-singer Utah Philips: “The earth is not dying, it is being killed, and those who are killing it have names and addresses.” That level of political directness is what is needed to rescue political theatre from irrelevancy. In order to save political theatre, we must “re-Marx” it.

To combat this de-Marxing and to re-Marx the theatre, I want to offer two pleas to my fellow political artists who are struggling with how to address the current moment of uprisings, plague, and economic crisis.

A Plea for Materialism and Class Consciousness On Stage

One of the most overused questions that young cultural critics ask on Twitter is, “How did the Friends afford those huge apartments?” While the question has certainly been beaten to death, it is still a very valid one and one that artists should consider, perhaps, a bit deeper. When artists create characters and give them lives that are completely devoid of financial stress but never comment on how that is, they are ignoring class in a way that is deeply dangerous. First, it establishes an “everyman” that is totally inaccessible to most people. There are very few people who live their lives without having to think about how to pay their rent. There are very few people who can love and lose and date and fuck and laugh and cry without also having to consider how to pay their student loans or credit card bills. These material worries must be considered by artists both in the construction and the content of their work because they are vital to understanding the world of the play.

In order to make any meaningful political art, we must first return to materialism on stage. Not materialism in the sense of buying a bunch of things you don’t need on Black Friday, but in the sense that our political art must be based on material reality. We, as artists, must understand what is actually happening in the world. This analysis will lead us to ask vital questions about our material situation: How do we pay our bills? How is our healthcare? How do we all work so many jobs but still struggle to pay our student loans? Why are we the victims of such systemic abuse and exploitation? These questions, which the vast majority of working artists in the United States face, lead us to look at our reality in a different way.

Bertolt Brecht’s Epic Theatre provides an example of what a Marxist theatre could look like. “Fear and Misery of the Third Reich” by Lake Crimson is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

We must no longer construct plays in the realm of ideas but in the realm of reality. Even if every single Trump voter saw the right production of A Raisin in the Sun, that wouldn’t necessarily change them into being warriors for racial justice. And even if it did, that still wouldn’t do anything to address the numerous white supremacists who are currently in elected government or the white supremacy baked into the criminal justice system. A Marxist approach to theatre must understand this in order to create political theatre that actually is effective at accomplishing its political goals of inspiring the audience to enact change.

That the Friends afforded those apartments changes how the characters relate to their problems, which then changes how the audience relates. But, by ignoring it, we’ve once again created an everyman that only represents the privileged. In addition, by ignoring class, we also flatten out all instances of oppression. So we can put plays like The Inheritance on Broadway as if these incredibly financially privileged gay men are representative of the struggles of the queer community writ large. This allows the audience to assume that the experience of privileged queer people is the default experience of every member of that community. The experience of a trans sex worker in Atlanta is fundamentally different than that of a cis gay advertising executive in New York, and to ignore that is to do both of them a disservice. I’m not saying, of course, that there is no place for the stories of a cis gay ad executive onstage but, rather, that if we want to explore any political questions in our art, then we must understand how class and class relationships shape every element of our situations.

So, whenever we create plays, we must understand how our characters fit into the larger world and make that explicit. For example, Rent has a wide swath of critiqueable elements but it does a fantastic job of grounding its characters in their economic reality. Characters do things because of their material conditions and we understand it as a major reason why they do what they do. A Marxist theatre must include class analysis in every play because without it, it is impossible to understand what is going on in reality.

A Plea for Visions of the Future

The world is broken—any child can tell you that. So, instead of simply churning out play after play that tells our audiences the world is broken, we should try to paint an image of the future. What could a future world look like? How do we get there? We should begin to think about creating visions of liberation, not just constant performances of oppression. I’m tired of seeing plays about queer people being beaten down. As a trans person, I wake up every day and know that my body and my identity are under attack. I don’t need to see more art that tells me what I already know. What I need to see is art that tells me that I can resist. That I can fight. That I can persevere. That we can create a world without oppression and bigotry. A Marxist theatre must place the hope of liberation at the center of its aesthetic.

And I don’t want the assumed audience of the privileged to be able to use theatre as their escapism any longer. Rather, I want political theatre to call them out, to show them their own role in society. But, I want this political theatre to not stop there and instead begin to provide a picture of what subverting complicity looks like. I want visions of liberation for the oppressed and visions of solidarity from the privileged. A Marxist theatre needs to both critique and empower its audience.

Theatre is undergoing an unprecedented evolution. No one knows what the art form can and will need to be after the pandemic. However, whatever we do, we cannot go back to making things with the exact same content and in the exact same way as we did before. Rather, we need to use this opportunity to radically reimagine what art should look like. For political theatre, I believe the way forward is to abandon the aesthetics of preaching to the choir and embrace the more revolutionary aspirations of a Marxist theatre.

I want to see a political art that tells us that those who oppress us have names and addresses. I want to see a political art that never lets the audience forget their complicity in the evils of society, because we must understand our own role in a system in order to fight it. I want to see a political art that mourns those we’ve lost without forgetting that those losses were preventable. I want to see a political art that can paint visions of a beautiful future without oppression. I want to see a political art that is rageful. I want to see a political art that is hopeful. I want to see a political art that’s real, that’s important, that’s vital, that feels like it could only be made right here, right now. And I believe that only re-Marxing the theatre will give it to us.

Ezra Brain is a genderqueer writer, theatre maker, teacher, and activist based in NYC. Their writing has been performed at the Tank, Literacy Theatre, Stop Pretending Theatre Project, Passaic Preparatory Academy, the New Masculinities Festival, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Exquisite Corpse Company, and Dixon Place. Ezra’s essays and articles have been published by Left Voice, Truthout, Musical Theatre Today, Howlround, and Harper’s Bazaar. They are an award-winning teaching artist, a proud member of Ring of Keys and the Dramatists Guild, and is a founding ensemble member of Embodied Theatre Project.