L ater this year, the United Nations will finish hosting the final negotiations on a new conservation treaty for the high seas, as waters that lie outside national jurisdiction are known. These cover more than half of Earth’s surface and contain much of the planet’s biodiversity. The moment marks a tremendous opportunity in humanity’s losing battle against biodiversity loss.

Thus far, however, conversations about how best to protect the high seas have missed a crucial element, one that could well be the single boldest, most important conservation move that humankind could make: recognizing the property interests of the marine species now living there.

Every whale and shark and sea turtle, every tuna and toothfish, every octopus and even every salp and sea urchin and anemone, has a right to own their part of the ocean.

What does it mean to say that animals have a right to own property? To many people this might seem like a radical idea. Those who follow animal law might say that it’s too big an ask. After all, it’s generally understood that in the United States and most of the world’s nations, animals have very limited legal rights. When activists have fought for legal personhood for animals—as when the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals sued SeaWorld for allegedly violating the 13th Amendment rights of orcas, or the Nonhuman Rights Project’s habeas corpus lawsuits on behalf of captive chimpanzees and elephants—they have usually lost.

It’s not so unprecedented, though. Many existing laws afford certain non-human animals legal interests to the environments in which they live. In the United States, for example, thanks to the federal Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, a golden eagle’s claim to the tree in which she nests outweighs the right of the tree’s human landowners to cut it down. Most public lands—approximately one-third of the landmass of the United States—are partially managed for animal interests. In the past decade, most states have enacted laws allowing pets to own property bequeathed to them in trust. Some tribal nations in the U.S. have afforded legal personhood to natural entities, such as wild rice in Chippewa ceded territories, which would allow humans to file lawsuits in tribal courts on behalf of rice. Outside the U.S., New Zealand’s Whanganui River was granted legal personhood in 2017, and Ecuador’s constitution explicitly recognizes the rights of nature to persist and regenerate. Once-unthinkable assertions of rights for nature’s beings are becoming commonplace.

These developments lay the foundations for explicitly recognizing wildlife as property owners. In contrast to how legal scholars historically viewed property—with ownership as an all-or-nothing affair—new models envision property rights as overlapping, a pluralistic conception of ownership in which humans and nonhumans alike can both have legally actionable interests in the same physical space. In this way, modern property law is beginning to embrace what many Indigenous cultures never forgot: Plants and non-human animals are our co-participants in life on Earth.

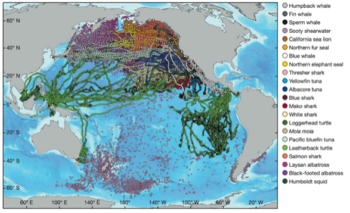

A map of the Pacific Ocean overlaid with tracking data from 23 species of large marine predators underscores how the high seas teems with life.

Global Tagging of Pelagic Predators

As applied to the high seas, this suggests that marine species could be understood as owners of the oceanic commons they occupy or, at least, co-owners with the recognized interests of nation-states. Under nearly every legal standard except the unstated qualifier of being a member of the human species, marine animals have property interests to the ocean.

What would this mean in practice? It could take a number of legal forms. One option is for marine species to hold ocean waters in trusts, similar to existing trusts for domestic animals. Humans would be appointed to manage ocean ecosystems for the benefit of the nonhuman living there. They wouldn’t need to consider the fate of every individual fish, but would be legally required to protect the well-being of species and populations.

Alternatively, the United Nations might look to the influential work of philosophers Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, who have theorized that different kinds of animals could be accorded different types of citizenship. Donaldson and Kymlicka write that domestic animals ought to be treated as full citizens of our own societies, while wild creatures can be likened to citizens of other nations. The United Nations might might even create a legal nation-state for marine species, with humans representing them in international affairs.

The United Nations could also simply list marine species as a member of the ocean commons, affording legal recognition of animal interests alongside that of the nations that collectively own the high seas. This would require subsequent treaties to consider wildlife interests.

In all these cases, a formal recognition of rights would advance marine species’ interests in the high seas—and not merely through the human-centered goal of sustainable fisheries management of fisheries, but by elevating the larger biodiversity goals that are at the center of the high seas treaty negotiations now taking place.

Right now, however, negotiators at the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction—as the U.N. body drafting the treaty is formally known—are actually moving in the opposite direction. They’re considering dividing the high seas between nations and regions. Nonhuman rights are not on the table.

To be sure, this is part of conversations that also include proposals for marine protected areas and restrictions on high seas fishing, both of which of which would do much to advance the interests of non-human ocean users. But divvying up the ocean without formally acknowledging the ownership interests of the creatures now living there replicates the fatal flaw that colonial governments made when they demarcated land boundaries. Rather than being required to consider the rights of wildlife in future actions, countries and regional management organizations will be able to diminish them even further.

That’s especially likely if regional fisheries management organizations acquire more power, which seems likely. They have a poor track record of biodiversity preservation—and, if given the chance, nations engaged in economic competition over the high seas’ resources will engage in a race-to-the-bottom. Devastating biodiversity loss will almost certainly occur, hastening the sixth extinction.

To avoid further expropriating Earth from other species, the new treaty should permanently title the high seas to its animal occupants. This would radically shift humankind’s trajectory—but, vitally, it would not eliminate human uses of the high seas. Humans could still catch fish and ship goods. It would simply require animal interests in having thriving ecosystems to be represented far more robustly than they have been.

The high seas represents a rare opportunity to preserve animal interests on a global scale; the United Nations has the power to shift the course of life on Earth for the better. We must not waste it.

Karen Bradshaw is the author of Wildlife as Property Owners: A New Conception of Animal Rights. She is a Professor of Law and the Mary Sigler Research Fellow at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University.