Including a special interview with Tom Soto, Prisoners Solidarity Committee observer.

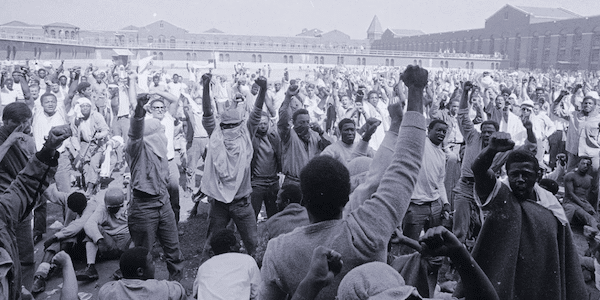

On Sept. 9, 1971, approximately 1,500 prisoners in Cell Block D seized the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York, after submitting a 27-point manifesto to the prison administration in an attempt to address the torturous conditions inside the prison.

At the time of the uprising, 2,300 prisoners were sandwiched into a prison built for barely 1,600 people. White supremacy behind the walls was evident everywhere, from how prisoners were housed to brutal work assignments.

Prisoners were allowed one shower per week and one roll of toilet paper a month. They labored for five hours a day and were paid between 20 cents and $1 for the entire day. For 14 to 16 hours, they were locked in tiny 6-foot by 9-foot cells.

A revolutionary mood

It is critical to understand the broader historical context in which this rebellion took place. How could people who were so beaten down, whose lives hung in the balance at the whim of a guard, take such heroic action?

Outside of the jails and also inside many prisons, a battle was raging for the national liberation of Black, Puerto Rican, Indigenous and Chicanx people. A new revolutionary mood was sweeping the country to end all kinds of oppression.

Millions of people were protesting the Vietnam War. The women’s liberation movement was beginning to blossom. The Stonewall Rebellion had sparked a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and Two Spirit (LGBTQ2S) liberation movement. Just two years later, the occupation of Wounded Knee by the American Indian Movement (AIM) took place.

The McKay Commission (New York State Special Commission on Attica) later commented:

With the exception of Indian massacres in the late 19th century, the State Police assault which ended the four-day prison uprising was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.

Organizing behind the walls

Serious organizing was going on inside Attica prior to the rebellion. Many of the groups outside the prison were reflected inside, including the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords, the Nation of Islam and the Five Percenters. Many had study groups. The Attica Liberation Faction developed in this period.

In July 1971, the Attica Liberation Faction presented a list of 27 demands to Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. This list of demands was based on the Folsom Prisoners’ Manifesto crafted by Chicanx prisoner Martin Sousa in support of a November 1970 prisoner strike in California. (For more background, see Project NIA.)

Then, on Aug. 21, 1971, Black Panther leader George Jackson was gunned down by racist guards in California’s San Quentin prison. Prisoners all across the country, including several hundred in Attica, went on hunger strikes. The assassination of George Jackson became the glue that allowed the Attica prisoners to unite across religions, nationalities and political factions.

The prisoners’ Paris Commune

On Sept. 9, Attica prisoners seized the facility. They took corrections officers hostage to ensure that their protest would be heard, since they had received no response to their manifesto from the corrections commissioner or governor.

While the events that took place on Sept. 9 were spontaneous and began as a clash between guards and prisoners, the level of organizing and what became a full-scale uprising were the result of the revolutionary leadership and consciousness that had grown during this period.

What’s remarkable is the high degree of organization and discipline of the thousands of prisoners who took part. They elected a central committee, which rotated chairpeople; they organized a 33-person observers’ committee, which included not only attorney William Kunstler, Black Panther Bobby Seale, New York State Assemblymember Arthur O. Eve, and representatives of the Young Lords, but also Tom Soto of the Prisoners Solidarity Committee.

Demands were continually being developed. A major one was amnesty for all prisoners.

Countless photos show the rows of tents, preparatory ditches and many of the other measures the prisoners organized. They voted on demands and rationed food and water for survival. During the entire occupation, the 40 hostages were treated humanely.

The concrete demands that developed during the insurrection included all aspects of survival in the prison, including health, food, ending solitary confinement, the right to visitation and a list of labor rights, including the right to a union and an end to exploitation.

The first time the working class took power into its own hands was the insurrection known as the Paris Commune of 1871. The communards canceled rents, recognized women’s rights, abolished child labor, took over workplaces and set up their own form of government. The commune served as a historical example to many revolutionary socialists of the potential for a workers’ state. It was ultimately put down in blood, but the lessons remain.

A century later, on Sept. 13, 1971, Gov. Rockefeller ordered the storming of Attica prison. With helicopters flying overhead, close to 1,000 state troopers, national guard troops and prison guards fired into the yard, killing 39 people and wounding 85 in what can only be described as a massacre. This took place in just 15 minutes.

Many of those wounded received no medical care. The prisoners had no guns or bullets to defend themselves.

The press screamed that the 10 captive guards who died had their throats slit. But autopsies showed that all 10 had been shot to death by Rockefeller’s storm troopers.

What happened in the immediate aftermath of the slaughter is too painful to fully describe. Prisoners were stripped naked, beaten, made to run through gauntlets of guards and brutally tortured. Guards stormed into the yard chanting “white power.”

A battle cry for liberation

Nevertheless, the Attica uprising and the massacre stirred prisoners everywhere. It’s estimated that 200,000 prisoners protested and held strikes in its aftermath. The number of prison rebellions doubled.

It continues to serve as a beacon today for those fighting against racism and mass incarceration and for workers’ rights everywhere.

Video: Tom Soto, Prisoners Solidarity Committee observer, speaks