A few days before the Nicaraguan presidential elections on November 7, Facebook and other social media companies began closing down many of the pages used by Sandinista supporters in their campaign to re-elect President Daniel Ortega. This blatant censorship move was said to be because they had discovered “troll farms” operated by government agencies. But many of the 1,500 accounts closed appear simply to belong to pro-Sandinista journalists or young commentators. TikTok, Twitter and Instagram took similar action, and Google said that it has closed 82 YouTube channels and three blogs in a related operation.

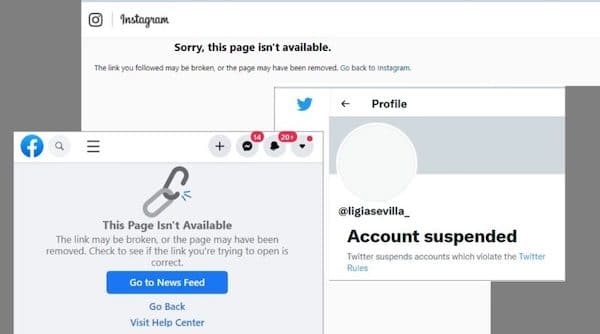

Among those closed were several well-known pro-Sandinista accounts with thousands of followers on Facebook-owned Instagram, including those of the online new sites Barricada, Redvolución and Red de Comunicadores.1 They even suspended the popular fashion organization Nicaragua Diseña.2 When such websites attempted to create new accounts, they were also blocked.

Censorship extended to neutral websites covering the election. For example, Carta Bodan’s daily newsletter on November 2 carried brief descriptions of five opposition candidates.3 When colleagues tried to share this link on their Facebook pages it was rejected. The fact that there are five opponents of Daniel Ortega standing might be an inconvenient truth, of course, given that many of the reports of Facebook’s censorship repeated the U.S. government’s contention that the Nicaraguan elections are a “sham” with no real opponents (despite the fact that two of the parties standing were in government between 1990 and 2007).4

Facebook’s head of security, Nathaniel Gleicher, tweeted justifications for its actions, even admitting that “this is a domestic op, with links to multiple gov’t institutions and the FSLN party. We don’t see evidence of foreign actors behind this campaign.” Gleicher failed to respond to accusations that huge numbers of genuine accounts had been disabled.5

The Grayzone’s Ben Norton contacted several pro-Sandinista journalists and commentators who had lost their Facebook or Twitter accounts.6 These included young Sandinista Ligia Sevilla, who attempted to show her genuine status on her Twitter account, which was immediately suspended.7 The same happened to well-known Sandinista activist Daniela Cienfuegos.8 Darling Huete, a journalist, had the same experience.9 Some, like ElCuervoNica,10 managed to set up alternative accounts. Effectively many commentators suffered double censorship: blocked because they were falsely accused of being bots, then prevented from proving that the accusations were false when they posted videos of themselves as real people. One journalist who complained to Facebook was simply told that “For security reasons we can’t tell you why your account was removed.”

Exploring the motivations for Facebook’s actions, Norton points out its government connections. For example, Gleicher was director for cybersecurity policy at the National Security Council and previously worked at the Department of Justice. Other senior Facebook executives involved have similar government connections.

International media such as Reuters and the BBC simply took Facebook’s justification at face value–that it had disabled a “cross-government troll operation.”11 Even media such as Aljazeera, often critical of the U.S. government, carried reports on what Facebook had done without adverse comment.12 Apart from The Grayzone, only the U.K.’s Morning Star appears to have criticized Facebook’s decisions.13 Anti-Sandinista news sites, such as Artículo 66, listed the accounts affected, calling them “propaganda” and disseminators of “false news,” even though they are themselves well-established propaganda sources for the opposition.14 None questioned why this had occurred days before a crucial election, or how it happened that action was coordinated across different social media outlets. The Financial Times reported, without comment, that the Facebook pages were followed by 784,500 users, even though this might have alerted them to the fact that most if not all the pages were genuine.15

The FT even compared the government’s operation to that of the Russian government’s St. Petersburg troll farm, accused of meddling in two recent U.S. elections.16 It ignored a crucial difference: that the Nicaraguan accounts closed were engaged in campaigning during their own country’s elections, not interfering in anyone else’s. Even more obviously, having made this comparison, it failed to ask why Facebook is itself interfering in an election campaign, and whether it is doing so at the behest of the U.S. government.

John Perry is a writer living in Masaya, Nicaragua.

Sources:

- ↩ Original links: instagram.com; instagram.com; instagram.com

- ↩ Original link: www.instagram.com

- ↩ See cartabodan.net

- ↩ “Blinken accuses Nicaragua’s Ortega of preparing ‘sham election’,” www.reuters.com

- ↩ See twitter.com

- ↩ “xxx,” thegrayzone.com

- ↩ See twitter.com

- ↩ See twitter.com

- ↩ See twitter.com

- ↩ See twitter.com

- ↩ See “Facebook says it removed troll farm run by Nicaraguan government,” www.reuters.com xxx and “Cómo funcionaba la ‘granja de troles’ desmantelada por Facebook en Nicaragua,” www.bbc.com

- ↩ “Facebook says it shut down Nicaraguan government-run troll farm,” www.aljazeera.com

- ↩ “Facebook accused of censoring Sandinista media organisations ahead of Sunday’s election,” morningstaronline.co.uk

- ↩ “Estas son las cuentas de troles orteguistas,” www.articulo66.com

- ↩ “Nicaragua’s government accused by Facebook of running social media troll farm,” www.ft.com

- ↩ “Russian troll farm makes U.S. comeback,” www.ft.com