Nearly a decade ago, two Brazilian researchers, Heliana de Barros Conde Rodrigues and Maria Izabel Pitanga, made a remarkable discovery. They requested materials on the French philosopher Michel Foucault from the National Archive of the Ministry of Justice in Brasília and obtained a file on him compiled by an intelligence agency established by the Brazilian dictatorship, the National Intelligence Service (SNI). The file revealed that Foucault’s participation in a protest at a student assembly in São Paulo in 1975 had become the focal point of his surveillance by the SNI.1 Conde and Pitanga’s discovery left me with an elementary but irrepressible curiosity: did the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the United States compile a file on Foucault? It did not seem outlandish to think that Foucault would have caught the attention of the FBI. He had visited the United States with great frequency in the 1970s and 1980s. Foucault had also established a reputation as a radical intellectual with a history of militant engagements at the time of his initial visits to the United States. He had thrown his support behind Marxist students in Tunisia who had revolted against the authoritarian regime of Habib Bourguiba in the late 1960s.2 And, in the two years between Foucault’s first visit to the United States in March 1970 and his second visit in March 1972, he had immersed himself in the activities of the Prisons Information Group (GIP), which he had founded with others to disseminate the voices of prisoners. Foucault also arrived in the United States for the first time when the FBI was still undertaking its notorious counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) of clandestine operations against a wide range of groups on the left, including the Communist Party, Puerto Rican independence groups, the Socialist Workers Party, the civil rights movement, the Black Panther Party, the American Indian Movement, the student movement, and the New Left.3 While Foucault does not appear to have been involved in the political activities of any of these groups during his visits to the United States, he had anonymously co-authored a portion of an investigative report that the GIP published in November 1971 to counter the official narrative of the assassination of Black Panther Party member George Jackson at San Quentin prison in August 1971.4 Foucault’s overall profile as a radical intellectual alongside his support for Marxist students in Tunisia and prisoners in France as well as his deep involvement in a group that had produced a pamphlet on the assassination of a Black Panther Party member could have been enough to put him on the radar of the FBI.

There are also allegations of a complicity between Foucault and the U.S. national security state that render the task of unearthing any documentation about him from this state all the more urgent. The history of these allegations goes back to two incidents at the tumultuous Schizo-Culture conference at Columbia University in November 1975. The organizer of the conference, Sylvère Lotringer, recalls that the first incident took place right after Mark Seem read Foucault’s paper “We Are Not Repressed” in English. “Suddenly,” Lotringer recounts, “a man sprung to his feet and, raising his voice and pointing his finger in Foucault’s direction, accused him and the GIP of having been paid agents of the CIA [Central Intelligence Agency].”5 The random accusation left Foucault flustered and defensive. Audience members hastily approached him to ask if the allegation was true.6 The next day another provocateur levelled the same accusation against Foucault and the psychiatrist R. D. Laing. At that point, Foucault went on the offensive by responding sarcastically, much to the delight of his audience.7 The identity of the second provocateur is unclear, but Lotringer identified the first as a former Swarthmore College professor and member of Lyndon LaRouche’s National Labor Committees.8 He reminds us that at the time LaRouche’s “bizarre, erratic and anti-Semitic organization” used allegations of financing by the CIA to discredit leftists.9

Fast forward to 2021. Sadly, suggestions of a complicity between Foucault and the CIA are circulating again, albeit in a repackaged form. The charge this time is not the canard that Foucault was a paid agent of the CIA. It is that he was an unwitting agent of the CIA, an unwitting “asset” of the agency. Gabriel Rockhill makes this assertion in a series of online articles for The Philosophical Salon published by the Los Angeles Review of Books.10 Unlike the provocateurs at the Schizo-Culture conference, Rockhill has the merit of turning to the CIA’s own words about Foucault. But he does not furnish compelling evidence from these words to support his identification of Foucault as an unwitting asset of the agency. Rockhill does not refer to a file on Foucault from the CIA, as one might expect. He relies instead on a CIA research report titled “France: Defection of the Leftist Intellectuals” from December 1985. The report, which is dated over a year after Foucault’s death, is not about him. It is about the creation of a more hospitable political climate for U.S. policies in France through the shift to the right among French intellectuals. The report mentions Foucault three times in less than a handful of sentences. It identifies him as an “anthropologist” who “refused a position” in the government of François Mitterrand.11 The report also describes Foucault as a member of the structuralist school of anthropology that (along with the Annales school of history) contributed to a “critical demolition of Marxist influence in the social sciences.”12 Finally, the CIA report commends Foucault for harnessing his unparalleled status among French intellectuals to offer words of encouragement to the new right. “The New Right,” the report concludes, “can point to kudos from Michel Foucault, France’s most profound and influential thinker for, among other things, reminding philosophers of the ‘bloody’ consequences that have flowed from rationalist social theory of the 18th-century Enlightenment and the Revolutionary Era.”13

The CIA clearly cherrypicked a few well-known moments in Foucault’s intellectual and political life to produce a view of him as an important figure in helping transform the intellectual landscape of France in a more anti-Marxist, anti-communist direction conducive to U.S. policies. Rockhill, however, goes even further than this view. He latches onto the meager words about Foucault in the CIA report as damning proof that the agency considered him an unwitting asset. In Rockhill’s words, “he [Foucault] is presented as being an asset” and “the CIA understood that he [Foucault] was an asset.”14 Yet it does not take a close exegesis to arrive at the conclusion that the anonymous author or authors of the CIA report did not consider Foucault an asset. And for good reason: the reference to an unwitting “asset” evokes the subjection of a person to espionage operations that result in his or her unintentional transfer of information to the intelligence agency undertaking those operations. Yet there is nothing in the CIA report to suggest that the agency had subjected Foucault to espionage, and there was no reason to turn to espionage for the information about him in the report because that information dealt with episodes in his political life that were all part of a very public conversation in France. The identification of Foucault as an unwitting CIA asset thus springs from an astonishing sleight of hand.

There is also something paradoxical about a radical critic like Rockhill relying heavily on the word of the CIA to distill the supposed truth of Foucault’s politics. It would be easy to point to moments in Foucault’s intellectual and political life that undercut the agency’s view of him. Foucault signed a petition published in January 1973 calling for a demonstration in front of the U.S. embassy in Paris against the U.S. bombardment of Vietnam.15 In October 1975, Foucault forcefully denounced a wave of political repression by the U.S.-backed dictatorship in Brazil that targeted members of the Brazilian Communist Party.16 The next month he attributed the increasing sophistication of torture techniques in Brazil to American technical advisors.17 Foucault also repeatedly identified Marx’s Capital as a source of inspiration for a positive analysis of mechanisms of power at a time in the late 1970s when he was supposedly riding the fashionable wave of anti-Marxism.18 And toward the end of the 1970s Foucault wrote enthusiastically about uprisings in Iran that resulted in the toppling of the U.S.-backed regime in the country. These details may tempt one to joke that if Foucault was an asset of the CIA, he was going about his job in a terribly unsatisfactory manner.

One way to approach Rockhill’s provocation is to simply dismiss it as beneath repudiation because it amounts to a smear campaign, not unlike the attacks on Foucault at the Schizo-Culture conference. Another approach is to critically engage its content by questioning its premises, challenging the accuracy of its claims, and considering other historical and political details.

The problem with the first approach is obvious: ignoring an allegation on grounds that it lacks intellectual respectability is no guarantee that it will go away. It could continue to produce effects, and Rockhill’s articles do appear to have gained traction in some quarters of the left. The problem with the second approach is that it plays right into Rockhill’s hands by giving his provocation too much attention.

I have opted, to some extent, for the second approach. But I prefer to open a pathway to a third approach–one that tries to find a rational kernel in Rockhill’s provocation in order to turn it in a more productive direction. Rockhill raises the important question of the relationship between the U.S. national security state and Foucault. How exactly did this state view Foucault? How did it respond to him? What can that response tell us about the U.S. national security state as well as Foucault?

To answer these larger questions, I shift from speculation to the actual documents written about Foucault by the FBI, which I recently obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The answers, as readers will see for themselves, are quite different from what one finds in Rockhill’s articles. Far from complicity, what stands out in the FBI file on Foucault is an anxiety about his Communist past. This anxiety was so great that Foucault was outright denied visas to visit the United States throughout most of the 1970s. He only managed to visit the country after applying for visa ineligibility waivers and undergoing additional security screenings through the U.S. Embassy in Paris. The imposition of these additional administrative rituals suggests that the U.S. national security state viewed Foucault with suspicion for his original sin of membership in the French Communist Party (PCF). To put matters in more polemical but still cautious terms, the only file on Foucault from a U.S. intelligence agency that has been released to date, to the best of my knowledge, casts him as a suspect–not as an asset.

An online search with the keywords “Foucault” and “FBI” brought me to a link to the FBI digital library of documents obtained through FOIA requests, “The Vault.” A click on the link took me to a page with access to a PDF file titled “Michael Foucault.” The fact that there is a file on him in “The Vault” means that someone else had unearthed the file through an FOIA request. Far from deterring me, however, the knowledge that someone had already gone down this path left me wondering why something as ostensibly intriguing as an FBI file on Foucault had not garnered more attention.19 I opened the file bearing his Anglicized first name, and its meager contents left me with a mixture of excitement and disappointment as well as more questions than answers.

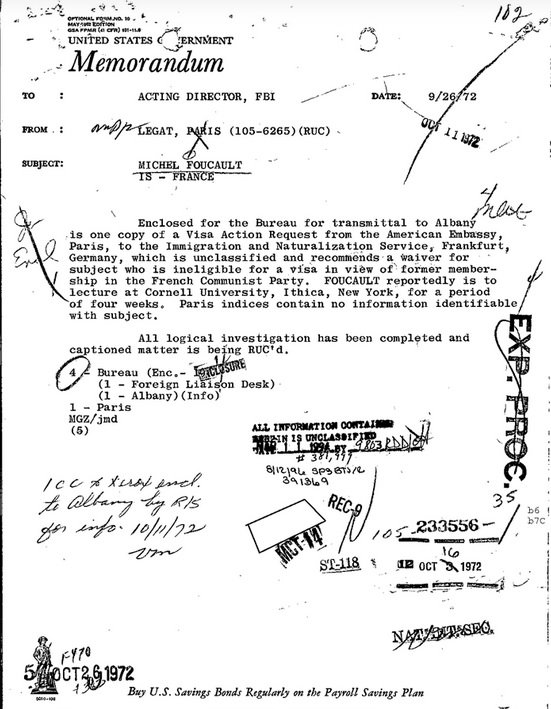

The file consists of only six pages. The first page is not even part of the original materials in the file. It contains a list in computer print of eleven deleted pages, almost all of which are marked as “Referral/Direct.” I learned from a researcher of the FBI that these pages were sent to other agencies for future release. The remaining five pages consist of two routing slips, two records forms, and a Memorandum from September 26, 1972 to the Acting Director of the FBI, all covered in stamps, markings, unintelligible scribbles, and signatures. The most important revelation in these materials is in the memorandum to the Acting Director of the FBI, who was at the time Louis Patrick Gray. The memorandum informed Gray that Foucault was “ineligible” for a visa to the United States because of his “former membership in the French Communist Party.” But it proceeded to recommend a visa ineligibility waiver for him so that he could go ahead with his planned four-week visit to lecture at Cornell University. The memorandum lends an intelligibility to the remaining documents in the file on Foucault. Those documents concern action requests over his visa status for the FBI director that emanated from the U.S. Embassy in Paris in April 1975 and March 1976. The checked boxes next to the items “All References (Subversive & Nonsubversive)” and “Subversive References Only” in the FBI records forms on Foucault from October 1972 and August 1973 respectively suggest that the agency scoured its records for any politically reprehensible information about him with a sharpened focus on his connections to and involvement in subversion.20

These details are of course quite fascinating. While the story of Foucault’s romance with California in particular has acquired almost mythical proportions,21 the story of his difficulties merely getting into the United States is not well known. These difficulties stemmed from Foucault’s Communist past, and they were important enough to draw the attention of the highest authority in the FBI years before Foucault had risen to intellectual stardom in the United States. The FBI’s focus on Foucault’s membership in a Communist Party he had abandoned nearly two decades beforehand (and then fiercely criticized) as the basis for his visa ineligibility also speaks volumes about the perfervid forms of anti-communism that have marked the history of national security institutions in the United States. However, the bareboned contents of the FBI file on Foucault in “The Vault” were disappointing and left me with some nagging questions. What was in the other eleven pages of the FBI file on him and would it be possible to obtain them? I submitted a FOIA request to the FBI in June 2020. To my surprise, it took the agency only a little over a month to respond substantively to my request in spite of a slowdown in the processing of FOIA requests due to the coronavirus pandemic. I received a response in the form of a PDF file from the FBI on July 13, 2020, hoping that the file would be a fount of further revelations about the relationship between the U.S. national security state and Foucault. And I could not help but wonder whether it would show that he had been subjected to surveillance. It turns out that the missing pages would be deeply illuminating, but not in the manner I had expected.

The originally missing pages of the file on Foucault that I received from the FBI consist almost entirely of Department of Justice Immigration and Naturalization Service applications from May 1973, April 1974, April 1975, and October 1977 as well as Department of State Visa Action Request forms from September 1972, April 1975, and March 1976. These additional documents make clear that the Immigration and Naturalization Service gave the stamp of approval to Foucault’s request for a visa ineligibility waiver from the Department of State. There is no variation in the underlying logic of the treatment of him in the ensemble of these newly released documents. They acknowledge Foucault’s original sin of membership in the PCF in the early 1950s but proceed to justify his entry into the United States on grounds of promoting cultural exchanges and international travel. The following “Remarks” from his April 1975 Visa Action Request form are typical:

Prof. Michel Foucault is ineligible under Section 212 (a) (28) of the Act due to former membership in the French Communist Party from 1950 to 1953.

Recent security checks have been negative and the alien has had several waivers in the past. He now wishes to accept an offer from the University of California at Berkeley to participate in academic conferences. He has a valid DSP-66 for the period of his stay.

In the interest of promoting cultural exchange between France and the United States, the Embassy recommends that a waiver be granted.

The reference to “the Act” is shorthand for the Immigration and Nationality Act. Section 212 (a) of the Act concerns grounds for inadmissibility to the United States. The version of the “Remarks” from September 1972 elaborates that the U.S. Embassy in Paris conducted security investigations into Foucault. It also indicates that he had received two previous visa ineligibility waivers from the Immigration and Naturalization Service office in Frankfurt, Germany.22 This detail is interesting for three reasons. First, it aligns perfectly with the number of times that Foucault visited the United States prior to September 1972, according to his partner Daniel Defert. Defert recounts that Foucault visited the country for the first time in March 1970 and then again in March 1972.23 Second, the reference to the two visa ineligibility waivers prior to September 1972 corroborates Defert’s observation that Foucault encountered difficulties getting a visa to enter the United States for the first time because of his former membership in the PCF.24 Third, in spite of this reference, there are no visa ineligibility waiver applications prior to September 1972 in the enlarged FBI file on Foucault. Indeed, the file contains no documents prior to that month. One can therefore safely presume that more materials on Foucault exist (or have existed) among the U.S. agencies concerned with his entry to the country and that these materials have yet to be publicly released.

The additional pages on Foucault from the FBI paint a more complete picture of the way in which the agency viewed him. What, then, would be the importance of the whole FBI on Foucault, at least as it is publicly available at this moment? One might think that apart from some revelations that should appeal to biographers of Foucault and historians of the FBI, the agency’s file on him would be little more than a dry administrative document, filled with lots of boring minutiae devoid of any larger theoretical significance. Yet Foucault himself underscored the importance of such administrative documents in the production of modern subjectivity. As he told a Brazilian interviewer in 1974, “Each one of us has a biography, an always documented past in some place, from an academic dossier to an identity card, a passport. There is always an administrative organism capable of saying at any moment who each one of us is, and the state can, when it wants to, follow our entire past.”25 He treated the file in particular as an embodiment of disciplinary writing that dates from police practices in late eighteenth-century France of producing reports on suspected individuals and distributing those reports to central and regional authorities.26 Foucault suggested that this form of disciplinary writing heralded a shift from the sciences of the species to the sciences of the individual; it constituted “the individual as describable, analysable object” with an “evolution” reflected in the development of “aptitudes or abilities.”27 For Foucault, we should pay serious attention to the file, rather than dismiss it as a mere bundle of administrative minutiae, because it produces what he called “an administrative and centralized individuality” through disciplinary mechanisms of visibility and writing.28 Files accumulate written observations about individuals that guarantee their continuous visibility to disciplinary authorities. Visibility in turn offers the possibility of a prompt punitive response to the acts of these individuals as well as to their potential behavior.29 In sum, the file is profoundly bound up with the production of individuality in the modern era. It constitutes an individual identity and imposes it on us through disciplinary mechanisms of visibility and writing. From this perspective, the FBI file on Foucault tied him to an individual identity he had long rejected.

Foucault’s elaborate and famous arguments about the role of surveillance in the exercise of disciplinary power lend themselves a bit too easily to the anticipation that the FBI file on him would reveal his own subjection to the surveillance by the agency during his frequent stays in the United States. And there would be something terribly fitting about revealing the subjection of the most distinguished theorist of surveillance in modern life to the surveillance of the domestic intelligence agency of the United States; it would serve to dramatize his views about the generalization of mechanisms of surveillance in the exercise of disciplinary power and their appropriation by the state. I initially approached the FBI file on Foucault tantalized by this possibility, but its contents did not live up to my expectations. Some details and, more importantly, omissions in the file grated against what I thought I might find in it.

On the one hand, the FBI file on Foucault incarnates a visibility in the sense of an accumulation of written observations about him. The U.S. Embassy in Paris also subjected Foucault to rounds of security investigations that consistently did not churn up anything prejudicial to his visits to the United States. On the other hand, there is nothing in the sixteen pages of the FBI file on Foucault to support the view that he was subjected to any surveillance by the agency during his visits to the United States, most likely because the security investigations at the embassy had already cleared him of any suspicions. FBI informants do not appear to have followed Foucault and the agency does not appear to have wiretapped him or even put together a dossier of his published writings. The FBI also did not discover that Foucault was a former PCF member through its own activities; he readily admitted his membership in the PCF when prompted through his visa applications for the Department of State. And it is not clear that the security investigations of Foucault at the embassy amounted to anything more than background checks. In short, there is no publicly available evidence in the FBI file on Foucault at this stage to affirm that the agency subjected him to surveillance during his visits to the United States.

In fact, what stands out from the file is the seeming obliviousness of the FBI to anything about Foucault except his avowed and distant past as a PCF member. There is absolutely no mention in the file of Foucault’s then more contemporaneous political views and engagements, such as his activities on behalf of the aforementioned GIP in France from 1971 to 1972. This circumstance is perhaps all the more surprising because as early as 1971 the FBI could have easily referred to published material from the United States that captured the spirit of Foucault’s radicalism. In an interview with John K. Simon published by the U.S.-based Partisan Review in the spring of 1971, Foucault depicted the university as a space of class struggle between an upper-middle class and a lower-middle class, affirmed the existence of an intensified class struggle in general, expressed his support for student strikers, and criticized the PCF for its conservatism.30 The FBI could have easily turned to the interview to get something of the flavor of Foucault’s politics at the time of his initial visits to the U.S. but it chose instead to dwell on a moment from his distant past. It is as if the FBI’s obsession with communism served epistemologically to inhibit the agency from a contemporaneous and robust consideration of Foucault’s politics. He had committed the original sin of joining the PCF long ago, and for the FBI this was the end of the story. Oddly, the narrowness of the agency’s focus clearly worked to Foucault’s advantage, because it took attention away from his more recent history of radical political views and engagements.

The expectation, then, that the FBI file on Foucault would open up to suddenly reveal a straightforward story of his surveillance does not appear to be the most productive way to theoretically engage the contents of the file. However, the file does illustrate a more general point about the exercise of modern power that Foucault began to systematically work out around the time that the agency drew him to the attention of its acting director in September 1972. Foucault insisted at the time that the concept of exclusion affords a very poor understanding of the productivity of modern power, because it reduces power to negative functions.31 He contended that the exercise of disciplinary power in capitalist societies transpires through a subtle logic of “inclusion through exclusion” rather than through the pure and simple logic of exclusion.32 In his emphatic words to a Brazilian audience in May 1973:

Nowadays, all of these institutions–the factory, school, psychiatric hospital, hospital, prison–aim not to exclude, but, on the contrary, to fix individuals. The factory does not exclude individuals; it ties them to a production apparatus. The school does not exclude individuals even while enclosing them; it fixes them to an apparatus for the transmission of knowledge. The psychiatric hospital does not exclude individuals; it ties them to a correction apparatus, to an apparatus for the normalization of individuals. The same happens with houses of correction or with the prison. Even if the effects of these institutions are the exclusion of the individual, they have as their primary aim fixing individuals in an apparatus for the normalization of men. The school, the factory, the prison or the hospitals have as a primary objective tying the individual to a process of production, formation or correction of producers. It is about guaranteeing a production or producers according to a determined norm.33

The same argument applies, mutatis mutandis, to the relationship between the territory of the United States and the “alien” Foucault, as disclosed in the FBI file on him. The agencies concerned with Foucault’s admission to the United States deemed him ineligible for a visa, but they did not proceed to simply ban him from the country on account of his past membership in the PCF. These agencies granted him visa ineligibility waivers, and justified these waivers mostly but not exclusively on grounds of academic productivity. Foucault received visa ineligibility waivers so that he could lecture at Cornell University in 1972, pursue tourism in New York City in 1973 and 1974, participate in “academic conferences” at the University of California at Berkeley in 1975, engage in research at the New York Public Library in 1976, and conduct “business” at the “University of New York” as well as tourism in 1977.34 In other words, the United States allowed Foucault to be fixed to its territory for limited but repeated periods of time so that he could (continue to be) constituted as a subject of academic labor and, more specifically, a producer of what became known as “French theory” as well as a consumer of tourism. The United States included, rather than excluded, Foucault.

However, there was still a punitive dimension to this inclusive relationship. Foucault had to apply for annual visa ineligibility waivers and undergo additional security screenings in Paris to get into the United States. Of course, the subjection of Foucault to these administrative requirements paled in comparison to the intimidation, aggression, and outright violence that the FBI unleashed against leftist groups in the United States through COINTELPRO operations, but it also suggests that the agencies concerned with his entry to the country did not forgive him for his original sin of membership in the PCF.

The materials in the enlarged version of the FBI file on Foucault cover the period from September 1972 to October 1977. Yet he visited the United States before and after that period. We are therefore left with the glaring question of how the FBI and other agencies concerned with his entry into the country treated him during the years of his other visits. We know that he had to apply for visa ineligibility waivers two times before September 1972 but his applications for those waivers do not form part of the paperwork in the enlarged version of the FBI file on him. Whether the agency even focused its attention on Foucault after 1977 remains a mystery. Did the FBI and the other agencies concerned with his entry to the United States continue to uphold the demand for visa ineligibility waivers from him as well as the requirement that he go through supplementary security checks after that year? Only the public release of additional materials will answer this question, but what we have so far in the FBI file on Foucault lends support to his theorizations of inclusive exclusion, and enriches them by underscoring the role of agencies concerned with the entry to national territory as its operators.

References:

- ↩ Serviço Nacional de Informações, Informação No. 5497/71/ASP/SNI/75, November 14, 1975, 1-14, Arquivo Nacional, Ministério da Justiça, Brasília, Brazil. The exact date of the delivery of the file to Pitanga can be found in Vivian Ishaq, photocopy of letter to Maria Izabel Vasconcellos Pitanga Espírito Santo de Araújo, April 23, 2012, in author’s possession. For the reproduction of three pages from the file, see Heliana de Barros Conde Rodrigues, Ensaios sobre Michel Foucault no Brasil: Presença, efeitos, ressonâncias (Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina, 2016), 119-21. For my own discussion of the importance of Foucault’s participation in protests in São Paulo in 1975, see Marcelo Hoffman, “From Public Silence to Public Protest: Foucault at the University of São Paulo in 1975,” in “Foucault and the Politics of Resistance in Brazil,” ed. Marcelo Hoffman, special volume, Carceral Notebooks 13 (2017-2018): 19-59.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, “Interview with Michel Foucault,” in Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 1954-1984, Vol. 3, Power, ed. James D. Faubion, trans. Robert Hurley et al. (New York: The New Press, 2000), 279-82. For details on Foucault’s engagement with Marxist students in Tunisia and the scope of his political activities in the country, see Ilka Kressner, “Critical Travels, Discursive Practices: Foucault in Tunis,” in Foucault on the Arts and Letters: Perspectives for the 21st Century, ed. Catherine M. Soussloff (New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016), 167-70.

- ↩ For an overview of COINTELPRO with an emphasis on its operations against the Socialist Workers Party, see Nelson Blackstone, COINTELPRO: The FBI’s Secret War on Political Freedom, 3rd ed. (New York: Pathfinder, 1988).

- ↩ Michel Foucault, Catharine von Bülow, and Daniel Defert, “The Masked Assassination,” in Warfare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy, ed. Joy James (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 140-58. For this section in the original report, see Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons, L’assassinat de George Jackson (Paris: Gallimard, 1971), 41-61.

- ↩ Sylvère Lotringer, “Introduction to Schizo-Culture,” in Schizo-Culture: The Event, ed. Sylvère Lotringer and David Morris (South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2013), 22.

- ↩ Lotringer, “Introduction to Schizo-Culture,” 22.

- ↩ Lotringer, “Introduction to Schizo-Culture,” 27.

- ↩ Lotringer, “Introduction to Schizo-Culture,” 24, 26.

- ↩ Lotringer, “Introduction to Schizo-Culture,” 25.

- ↩ Gabriel Rockhill, “The CIA Reads French Theory: On the Intellectual Labor of Dismantling the Cultural Left,” The Philosophical Salon (blog), Los Angeles Review of Books, February 28, 2017; Gabriel Rockhill, “Foucault: The Faux Radical,” The Philosophical Salon (blog), Los Angeles Review of Books, October 12, 2020; Gabriel Rockhill, “Foucault, Anti-Communism, and the Global Theory Industry: A Reply to Critics,” The Philosophical Salon (blog), Los Angeles Review of Books, February 21, 2021.

- ↩ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), “France: Defection of the Leftist Intellectuals,” December 1985, 1.

- ↩ CIA, “France: Defection of the Leftist Intellectuals,” 6.

- ↩ CIA, “France: Defection of the Leftist Intellectuals,” 14.

- ↩ Rockhill, “Foucault, Anti-Communism, and the Global Theory Industry.”

- ↩ “Appel à manifester devant l’ambassade américaine à Paris contre les bombardements au Vietnam,” in Signés Foucault & Cie, ed. Philippe Artières (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2020), 61-63.

- ↩ Hoffman, “From Public Silence to Public Protest,” 45.

- ↩ R. D. Laing, Howie Harp, Judy Clark, and Michel Foucault, “Roundtable on Prisons and Psychiatry,” in Lotringer and Morris, Schizo-Culture, 172.

- ↩ For a lecture from October 1976 in which Foucault turned to Marx’s Capital, see Michel Foucault, “As malhas do poder,” trans. Ubirajara Rebouças, Barbárie: Revista de cultura libertária. Especial anarquismo, Summer 1981, 23-27. See also Michel Foucault, Colin Gordon, and Paul Patton, “Considerations on Marxism, Phenomenology and Power: Interview with Michel Foucault; Recorded on April 3rd, 1978,” Foucault Studies, no. 14 (September 2012): 100.

- ↩ For the mere acknowledgment of the receipt of the FBI file on Foucault from two researchers who searched to no avail for a Polish secret police file on him, see Anna Krakus and Cristina Vatulescu, “Foucault in Poland: A Silent Archive,” Diacritics 47, no. 2 (2019): 99n23.

- ↩ Michael Foucault Part 01 of 01,” The Vault, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), accessed May 29, 2020.

- ↩ For a lively account of Foucault’s time in California, see Simeon Wade, Foucault in California [A True Story–Wherein the Great French Philosopher Drops Acid in the Valley of Death] (Berkeley: Heyday, 2019).

- ↩ Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), “Michel Foucault,” FOIPA Request No. 1468015-000, July 13, 2020.

- ↩ Daniel Defert, “Chronologie,” in Dits et écrits 1954-1988, Vol. 1, 1954-1975, by Michel Foucault, ed. Daniel Defert and François Ewald with the assistance of Jacques Lagrange (Paris: Quarto/Gallimard, 2001), 47, 55.

- ↩ Defert, “Chronologie,” 47.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, “Michel Foucault no Brasil: Loucura: Uma questão do poder,” interview by Silvia Helena Vianna Rodrigues, Jornal do Brasil, B, November 12, 1974, translation mine.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1973-74, ed. Jacques Lagrange, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 50.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 191, 190.

- ↩ Foucault, Psychiatric Power, 50.

- ↩ Foucault, Psychiatric Power, 50-52.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, “A Conversation with Michel Foucault,” interview by John K. Simon, Partisan Review 38, no. 2 (Spring 1971): 194-95, 196-97, 198, 200, 201.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, “Michel Foucault on Attica: An Interview,” interview by John K. Simon, Telos, no. 19 (Spring 1974): 156. This interview was conducted after Foucault visited Attica prison in New York state in April 1972. He credited his visit to the prison, which took place only seven months after the infamous massacre there, with helping precipitate his shift from an affirmation to a critique of the concept of exclusion. For an important instance of this critique, see Michel Foucault, The Punitive Society: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1972-1973, ed. Bernard E. Harcourt, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 2-3.

- ↩ Michel Foucault, A verdade e as formas jurídicas, trans. Eduardo Jardim and Roberto Machado, 4th ed. (Rio de Janeiro: NAU Editora, 2013), 113, translation mine.

- ↩ Foucault, A verdade e as formas jurídicas, 113, translation mine.

- ↩ FBI, “Michel Foucault.” It is not clear if the “University of New York” was a misnomer for New York University, the State University of New York, or the City University of New York.