Amid volatile markets, they (African states] are realizing they cannot afford to take sides by playing along the Western line in this so-called “cold war”. Thus, non-alignment can pave the way for de-dollarization and strengthening multipolarity. And it can also help mitigate a global food crisis.

In addition to today’s fuel and energy crises, food insecurity has been a major issue for a number of reasons and, with the current Russian-Ukrainian war, a global food crisis and hunger is a real risk. Unfortunately, this may pave the way for a kind of food diplomacy and food wars. Facing this scenario of insecurity, the European Union, together with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), is trying to employ its own food diplomacy in North Africa as part of the Western efforts to counter and isolate Russia. Moscow has been accurately describing the crisis as the result of sanctions and the West’s lack of diplomacy during the conflict, and many African nations are also perceiving it in this manner, which of course is a concern for Europe. The FAO is considering developing a food funding mechanism to help African countries and this (quite timid) initiative should be seen in this context. Even so, non-alignment is on the rise in the continent.

The whole food situation, in the context of sanctions and war, has its geopolitical, economic, financial, and currency aspects with profound implications. The Russian government suggests a number of proposals in order to improve Moscow’s cooperation with the African countries. They include establishing free trade zones, trade missions in the continent, and a Russia-Africa Trading House. The Russian Central Bank and its Ministry of Finance could come up with intergovernmental agreements with the African states to establish a trust fund to support businesses and a specialized import-export bank. Developing cooperation with friendly and neutral states is of course in Moscow’s best interests, but it would also tremendously benefit such countries.

Among other proposals–introduction of the Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), a kind of digital tokens which could be used, as well as cryptocurrencies, for mutual settlements and payments. The Russian Central Bank has already authorized Sberbank to issue and to trade digital financial assets, while Moscow is considering employing cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin for its gas and oil exports to countries such as China and Turkey. All these developments are hugely important because they mark the possible beginning of a global de-dollarization process.

However, in the case of Africa, Chainalysis, a blockchain analysis firm, released a report on April 14 which indicates that free float of cryptocurrencies is still too low to allow for large-scale transfers. This could change, though. On April 11, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo issued a joint announcement about the three countries’ plans to adopt the TONcoin blockchain, a project that was started by Telegram. The three countries stated crypto coins could become a central pillar of their economies. Kenya, Gana, and South Africa have also made some progress with CBDCs.

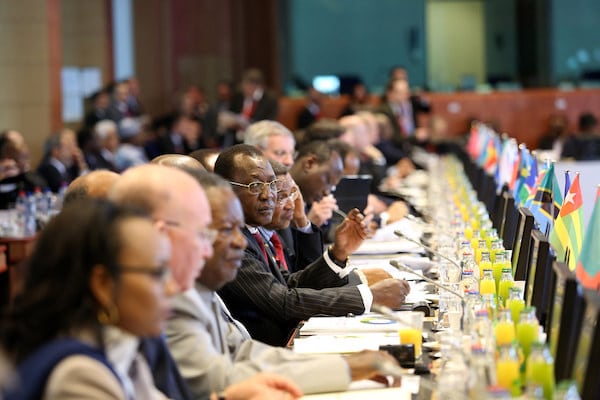

These new developments and their potential consequences are only made possible by a kind of a new nonalignment tendency. Even though the African Union condemned the Russian military operation in Ukraine, there is not a clear consensus among African leaders. In fact, amid the “new cold war” (as some have described it), many African nations are pushing for dialogue on the Ukrainian conflict and opting for neutrality. This is so due to many factors.

On April 7, the UN voted to suspend Russia from its Human Rights Council, and African countries largely abstained, which is yet another indication of the tendency described above–in spite of intense diplomatic pressure from the United States. Even Senegal’s President, President Macky Sall (a Washington’s ally) has followed the African tradition of nonalignment, which has its roots in the 1960s and is now gaining momentum again.

According to British-Nigerian journalist Nosmot Gbadamosi, Washington’s aggressive tone has not been very well received in the continent, whose leaders cannot help but notice the double-standard and hypocrisy pertaining to the sanctions and the focus on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict (which has serious humanitarian angles), while the American invasions of Libya and Iraq have not generated analogous responses. This is particularly ironic considering that the U.S. and the West are the main actors who have caused the Ukrainian-Russian crisis which started in 2014 and escalated in 2022–and they have fueled the intense Ukrainian provocations and Kiev’s bombing of Donbass which had been largely ignored by the Western establhsiment so far.

For example, in March, Mathu Joyini, the South African ambassador to the UN suggested the U.S. and its allies have been committing their own violations of the UN Charter and are now merely pursuing their own geopolitical agendas by invoking the humanitarian situation and championing the UN resolutions against Moscow. American senior diplomat reporter Colum Lynch writes that this poses a serious threat to Washington’s attempts to build a unified diplomatic “front” in support of Kiev.

Finally, the Western sanctions targeting Moscow also impact mostly Middle-Eastern and African countries.

All of this helps to explain why leaders from South Africa, Senegal, Central African Republic, and Mali, among others, have refrained from backing Washington’s position on Moscow. Amid volatile markets, they are realizing they cannot afford to take sides by playing along the Western line in this so-called “cold war”. Thus, non-alignment can pave the way for de-dollarization and strengthening multipolarity. And it can also help mitigate a global food crisis.

Uriel Araujo, researcher with a focus on international and ethnic conflicts.