In 1915, with the Panama-California exposition underway, a group of San Diego businessmen came up with a plan to sell Balboa Park. Not literally but figuratively. With the city’s crown jewel as the inducement, they placed ads in Midwest newspapers and then read the responses for clues about the class of the person who inquired.

At a pivotal moment in the city’s formation, a developer and his cohorts were setting aside homes for wealthy outsiders who could fatten the local construction and services sectors. They were picking and choosing the populace they wanted and creating a veneer of affluence in the national imagination that still exists today.

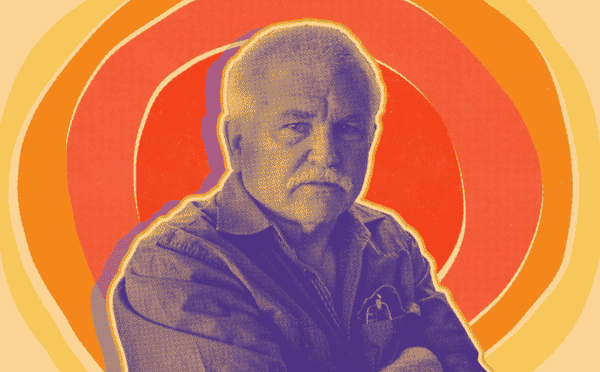

I think back on occasion to this little-known chapter in our history, and with renewed frequency after seeing a social media post last month about the writer who first brought it to my attention. The post announced that the San Diego scholar and activist Mike Davis had stopped cancer treatment and gone on palliative care. It went viral and led to an outpouring of support.

To alleviate anyone’s concern, Alessandra Moctezuma clarified a couple days later her husband wasn’t in any immediate danger. “Notwithstanding,” she wrote,

it’s wonderful to hear so many loving messages and we’ll continue to be strengthened by your affection and radical love.

Allow me to add my voice to the choir.

Davis is a giant of urban theory with incredible range. He’s written books about ecological disaster, famine, slums, labor movements, car bombs. He combs through highly technical literature and weaves disparate fields of study together to make sense of the various crises we’re now facing or will soon. He tried to sound the alarm about globe-crippling pandemics almost two decades ago.

Though several of his most popular books were written in the 1990s and early 2000s, they remain fresh and instructive because they identify not just symptoms but causes of ongoing problems in California and beyond.

The one I keep coming back to, and the one I cited above, is “Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See,” a collaboration with City College professors Kelly Mayhew and Jim Miller. It is a people’s history–including stories of rebellion and repression–and delightfully iconoclastic. At its core is an assault on the mythology of America’s Finest City, which, they argue, undermines any meaningful reflection of the social relations and extremes.

The book is ignored in most national reviews of Davis’s oeuvre. But it holds a special importance here because the histories of California tend to breeze over San Diego, as though the city really were, to paraphrase the novelist Raymond Chandler, nothing more than a climate.

In his 128-page essay at the start of the book, Davis wrote that San Diego’s benign reputation is undeserved: It has operated more like a private utility than a commonweal, dominated by a handful of men–often outsiders, often involved in scandal–who’ve manipulated a weak government to enrich themselves.

Many of the important debates of the 20th Century were not spurred by popular movements but by competing visions among the upper crust. On one side were the “smokestacks,” who favored industry and growth. On the other side were the “geraniums,” who desired cleaner landscapes and wanted to avoid the sins of Los Angeles.

The two visions were synthesized, at least for a while, when the Navy came to town. Federal dollars protected the economy against booms and busts, but also kept the blue-collar workforce conservative and docile. Without a base to fall back on, the occasional liberal reformer proved ineffective.

But while the city was quick to give away land to the military, it refused to build or subsidize affordable housing for immigrants and the poor. Officials let the private sector figure it out, but the private sector was never going to deliver. The result is what we see today–a sprawling panoply of upscale suburban homes and shopping malls.

The federal government built an affordable housing project, known as Frontier Housing Project, in Midway to address homelessness and squalor in the area. The project was separated by a no-man’s land buffer from Loma Portal neighborhood as seen in 1946. (Photo: San Diego History Center)

When the population of San Diego exploded before and during World War II, there were so many people living in automobiles, abandoned rail cars, trailers and all-night movie theaters that congressional committees dubbed it the nation’s worst defense-housing crisis.

For a time, urban development fell on the federal government, which completed the city’s public works plan in half the time and at a cheaper cost. But many of the new homes were built away from existing neighborhoods that already had access to utilities and public transportation.

There are plenty of other lessons in this seminal history of America’s eighth largest city, but the one that resonates for me is the chronic failure of San Diego leaders to plan for just about anything. The past is always catching up with us and we wonder why.

For Howard Blackson, an urban designer, Davis’s larger body of work shows how subtle barriers–like signs, hedges, fences, even “bum-proof benches”–isolate people from one another and make life more difficult for no good reason. Blackson has used Davis’s research in the classroom because it chronicles the increasingly militarized nature of our cities, from the architecture down to the police.

“It’s not that the system is broken. It’s that the system is built this way,” Blackson, a friend of Davis’s, told me. Above all, that’s what Davis preaches:

He hammers you with the urgency and the actual scandalous way we treat each other and just let it happen.

In Davis’s telling of history, one of the few successful, popular revolts in California in the 20th Century came from homeowners, many of whom had cut their teeth in opposition to school integration before turning their attention to real estate taxes. In an updated preface to “City of Quartz,” the book that brought Davis to prominence in 1990, he captured the cynicism underlying this form of politics:

Although many of the movement’s concerns about declining environmental quality, traffic and density were entirely legitimate, ‘slow growth’ also had ugly racial and ethnic overtones of an Anglo gerontocracy selfishly defending its privileges against the job and housing needs of young Latino and Asian populations.

Davis was writing about the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles, but these words could easily apply to San Diego today.

I recently asked Miller whether anything has changed since “Under the Perfect Sun” was published in 2003. Culturally and politically, he said, yes. Structurally, not so much.

With liberals in control of the city and the county, the climate is more favorable to the working class and that creates opportunities. We’ve seen an increased number of protests in recent years for racial justice and labor interests. But the cost of housing and homelessness continue to rise, and folks in south and southeastern neighborhoods still suffer from income and health disparities.

The book tells ugly truths about the city’s founding and leadership, or lack thereof, through the start of the 21st Century and that’s why so many locals cherished it. “I don’t want to overdetermine,” Miller said,

but we did something no one else had done.

Former City Councilwoman Donna Frye, who ran an insurgent campaign for mayor in 2004, told me that she’s a fan and encourages others, especially transplants, to read the book because it provides insight into why history keeps repeating. “We’re a whole lot better as a city for having people like Mike Davis,” she said.

When Lucas O’Connor, executive director of the Progressive Labor Alliance, moved to San Diego in 2005, he found the city in the depths of a fiscal crisis with debates about whether it was headed toward bankruptcy. A mayor, a congressman and two councilmembers all resigned within the span of a year. Reading “Under the Perfect Sun” showed how the chaos was rooted in a carefully constructed political system.

It taught him to look beyond the conventional wisdom. Buried in the city’s history was the potential for something new.

“San Diego certainly kept getting worse for a while,” he told me,

but it does seem like we’ve at least started moving towards a different vision of what government is for and what we value as a region.

Though the bane of Southern California boosters, Davis has found a receptive audience outside the academy where he taught. He grew up on the outskirts of the metro, in Bostonia, a community he once described as “the social dumping ground for San Diego,” and worked for a time as a meat cutter and truck driver. From his modest roots came respectability and an innate understanding of struggle.

Davis has spent his career encouraging readers to consider not just economic inequality but economic power. What he means by that is the concentration of decision-making in the hands of a self-interested minority that finds support in reactionary circles looking for on-demand pleasures at the expense of everyone else and the planet. To put it mildly.

The distinction between economic inequality and economic power is an important one. His urging that ordinary people become partisans of what’s politically necessary rather than what’s politically possible opens up the mainstream to previously unthinkable solutions.

One of the recurring criticisms of Davis’s books is that they’re too dark. His writing is often seething and incendiary, offering images of a society on the brink of collapse. But even his opponents from time to time concede that his depictions of urban life are accurate. That writing, as another columnist noted a few years ago, has aged far better than the criticism of it.

In 2020, a podcast host asked Davis how he counters the perception that his writing creates a feeling of immobility. Davis responded that hope is not a scientific category and the struggle for a better world shouldn’t be contingent on the probability of it coming to fruition.

“I still believe in character,” he said,

that people produce themselves through the moral choices and actions they take [regardless] of calculations of success or wealth or anything like that, actions that are rooted in solidarity and love for other people in the common condition.

It helps to remember that we are the cause of inequality, which means we have the power to reverse course. Davis never tires of pointing that out. Seeing the way forward depends on knowing the past and being honest about the failures and missed opportunities.

Nothing, in other words, is set in stone. There are alternative futures.