Recently in Iran’s largest city, Tehran, Mahsa Amini, a twenty-two-year-old Kurdish woman, was arrested by Iran’s “morality police” for allegedly wearing her government-mandated hijab inappropriately. She was beaten, and three days later, she died. The response from Iranians, and young Iranian women, in particular, was swift. Now, what was at first viewed as a protest appears to be spreading into a new revolution in Iran, the likes of which the country hasn’t seen in over forty years. Women are at the forefront of their demands.

Some analysts observing events in Iran and online will see these events as the first-time women have been at the forefront of a movement. Indeed, women have been at the forefront of most movements in Iran, but this is the first time that women’s demands to stop gender violence and discrimination are on the front line of Nationwide protests. As a sociologist who works on social movements, I understand the current protests for gender equality spreading in Iran as part of a decades-long struggle against women’s oppression. This movement isn’t just about protesting the Iranian government’s killing of a young woman for improperly wearing her hijab; it is, rather, the culmination of decades-long gender oppression and misogynist policies in Iran—a protest that is quickly becoming a revolution.

What you are witnessing in Iran has a long history of resistance against a theocratic regime that seized power after the 1979 revolution with violence and brutality. In the aftermath of the Islamic revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini declared the Hijab code compulsory, forcing women to cover their hair and bodies. Soon thereafter, Islamists approved Sharia laws to govern the lives and bodies of women.1 2

Rather than accept these new limitations on their bodily freedom, on International Women’s Day, March 8 of, 1979, merely weeks after the revolution, thousands of women organized massive street protests demonstrating against new forms of gender oppression and Sharia laws meant to limit their freedoms. Their main slogans were “We didn’t have a revolution to go backwards,” and “Equality, Equality, Neither Chador Nor Headscarf.” Ultimately, these street protests were brutally suppressed, and Iranian society did little to support women, and social and political groups mostly did not support these protests because they felt that the protests risked sparking a counter-revolution.3 4 5 At the time, women’s demands were not a priority.

Yet what was at stake in 1979, and what continues to be at stake in the current and spreading protests in Iran, is not simply a movement against only laws enforcing compulsory hijab. Indeed, in the aftermath of the 1979 revolution, women’s roles in Iranian society had fundamentally shifted. Islamist leaders successfully implemented gender segregation, usurping many of the rights women had gained through historical movements. From the beginning of the Islamic Republic, the state used all tools at its disposal at the time, including mass media, educational systems, policies, and the legal system, to portray the Hijab code and Islamic laws limiting women’s social roles and rights as valuable social norms and rules.

One of the tools employed over the last four decades to enforce gender oppression has been the “morality police”—the very entity being held responsible today for Amini’s untimely death. Street Guidance Patrols regularly roam public spaces to ensure women observe the Hijab code and actively discouraging the use of cosmetics. Other morality guards exist in almost all governmental institutions and all public or private universities in Iran, enforcing not only women’s dress code, but also women’s and men’s behaviors according to the gendered Sheria ideological system.

The result of this decades-long system of gender oppression and misogynist policies in Iran has touched every aspect of women’s lives. Gender segregation has been systematically applied to all areas where women can be seen in public: schools, public transportation, universities, recreational spaces, and workplaces. As a result, women have been pushed to the sidelines, their working and educational conditions becoming ever more precarious. In the decades since the revolution, women were routinely fired because of their dress, behavior, and lifestyle. Women were forbidden to pursue many fields of study in universities and were barred from certain types of jobs.6 7

One of the few outlets available to women in the aftermath of the revolution has been to pursue higher education in universities. From the 1980s to the present, women have occupied an ever-larger presence in universities. Yet their status as highly educated citizens have not opened additional opportunities for women in the workplace. The statistics here are illustrative. Prior to the revolution, in 1976, women’s literacy rate was 35%, while their participation in the labor force was 12.9%. In 1986 only 8.2% of women were employed in Iran, in spite of a literacy rate of 52%.8 In 2016, the most recent year for which statistics are available, women’s participation in the labor force was 14.9%, an impressive gain from the 1986 figure, yet their literacy rate was 82.5%.9 Today, in spite of their impressive educational attainments over decades, the majority of impoverished people in Iran are women,10 who, under Sharia law, are meant to be economically dependent on men. This is just one of many of the injustices women have faced over decades, a context critical for understanding the current protests in Iran.

Meanwhile, Sharia law governing family and marriage has systematically pushed women’s status to the margins. Women lack equal rights in marriage, divorce, and custody of their children. Birth certificates name a child’s father, but their mother’s name is omitted, thereby erasing their legal rights to their own children. Child marriage is legal. A woman’s choice of job, place of residence, or ability to leave the country depends entirely on permission from her husband. Polygamy was legalized and encouraged, and women found to be with a man other than their husband were put to state-sanctioned death.11 12

Since the 1979 revolution, legally and officially, women have become second-class citizens in ways that were not the case prior. Before 1979 we had many gender inequalities in Iran, but this gender apartheid was new. Also, it is clear that women who belong to powerful states families and believe this ideological system have received many benefits, for example, they are in some governmental positions while working-class women were in more challenging and more fragile conditions.13 Although the general term “women” needs more caution, women, especially working-class women and women of ethnic and religious minorities, suffered most and lost most from the Islamic regime. It can convince us that women were the biggest losers of the Islamic regime.

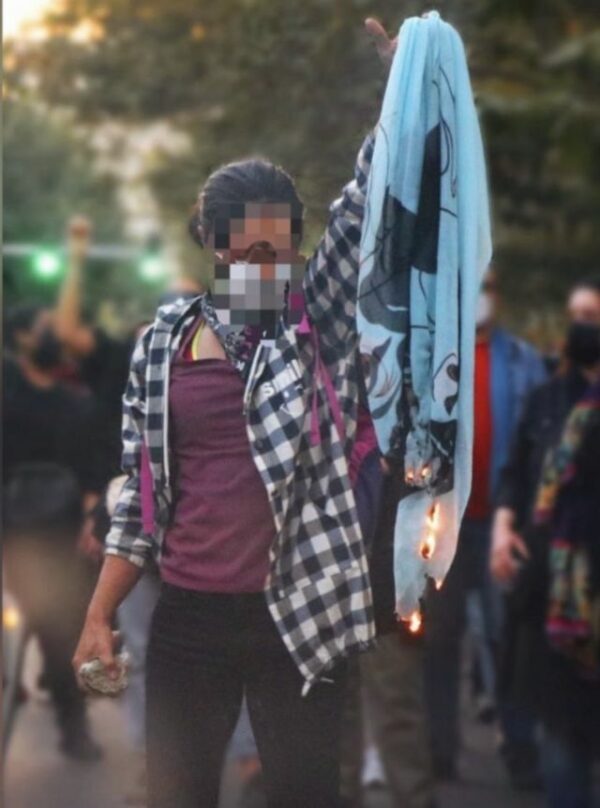

However, Iranian women have never been silent victims of their marginalized status. In addition to organizing the first mass protest against the Islamic regime on March 8, 1979, women have been using overt and covert tools to counter their own oppression for decades. Women are active in grassroots movements to improve gender equity, address environmental problems, and improve rights for children and ethnic minorities. For example, a few years ago, girls of Enghelab Street protested against the compulsory hijab with social performance by removing their headscarves in the street as a sign of protest against the mandatory hijab in Iran. Women’s, and particularly young women’s, recent removal and burning of their headscarves on the streets of Iran are a continuation of these earlier protests. Indeed, across social movements in Iran since the revolution, women have always been participants, and often they’ve been at the forefront of protests against oppression.

What is new in the recent protests is the national and international attention their actions are currently receiving, and their demands on Hijab are clear and at the forefront. In fact, the main slogan of the current movement, “#Woman, Life, Freedom”, originated from a liberation movement, Kurdish women partisans in Turkey and Syria, who have endured decades of ethnic discrimination and have a history of fighting against patriarchy, national oppression, tyranny, the consequences of colonialism, and ISIS. Their message is spreading far beyond Iran. Iranian women on the front lines of the movement draw attention not only to their own oppression but also to that of Afghan women. Women across the Middle East and beyond are taking to social media and to the streets to support their sisters on the front lines.

Iran has had many protests in the last decades. Iranian society has definitely faced an accumulation of different problems. The Iranian regime has been inefficient in different fields; regarding economic issues, one of every three Iranians lives below the poverty line.14

The response by those in power in Iran has been consistent: violent repression. Iranians’ collective memory is full of oppression and humiliation. Recently, the Islamic state has responded to the spreading movement by brutally killing people. While official statistics are unavailable, it is estimated that the Iranian government has killed at least 200 people, 19 of whom were children.15 On September 30, the IRI shelled and killed at least 95 in Zahedan (belong to Baloch ethnic group) people emerging from prayer. Yet the state’s violent oppression tactics are having the opposite effect: the revolution is spreading.

Slogans like “This is a women’s revolution, the whole system is the target” and “Don’t call it a protest, it’s called a revolution,” demonstrate wider societal commitments to progressive change in spite of the violence with which those in power attempt to silence them. And the movement is spreading. Recently, this revolution has gone beyond the boundaries of gender, ethnicity, nationality and religion.

This week Baloch women (the most deprived and oppressed women in Iran due to ethnicity, gender, and religion) have made a statement in joining the Women, Life, Freedom movement and that they stand and fight with their sisters to build the first women’s revolution in history.16 Among those joining the movement in massive numbers are young people: university and high school students, also artists, and athletes who risk their lives in order to build a more equitable Iran for all. Several of the laborers central to the Iranian economy are calling for strikes to support the movement: teachers and labor unions, the most notable recently being workers of Asalouye and Abadan Petrochemical.

As an Iranian woman and a sociologist with expertise in social movements, the spread of this revolutionary spirit with young women at the forefront is as inspiring as observing the state’s brutal oppression tactics are alarming. Yet it is important to understand this moment in the wider context. Mahsa Amini’s murder by the morality police was a spark igniting embers of anger and activism that have been smoldering for decades.

This is a women’s revolution and is going beyond the boundaries of ethnicity, nationality, and religion. The support of various ethnic groups for these protests is the strength of this revolution. This revolution has targeted the entire structure of discrimination and reaction in Iran and the Middle East. This does not mean we will soon see the result of this women’s revolution; there are still traditional layers in society who are worried about liberating slogans and movements. This does not mean that anti-movement groups are not active, they might cause deviations, the Islamic Republic may severely and brutally suppress this movement. With all the real threats and conditions, this means that we are at the beginning of an end.

Notes:

- ↩ Moghissi, Haideh. 1996. Populism and Feminism in Iran: Women’s Struggle in a Male-Defined Revolutionary Movement. New York: St Martin’s Press

- ↩ Higgins, Patricia J. 1985. “Women in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Legal, Social, and Ideological Changes.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 10 (3): 477—494.

- ↩ Moghissi, Haideh. 1996. Populism and Feminism in Iran: Women’s Struggle in a Male-

- Defined Revolutionary Movement. New York: St Martin’s Press

- ↩ Poya, Maryam. 1999. Women, Work and Islamism: Ideology and Resistance in Iran. London: Zed Books

- ↩ Haeri, Shahla. 2009. “Women, Religion and Political Agency in Iran.” In Contemporary Iran: Economy, Society, Politics, edited by Ali Gheissari, 125—150. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↩ Poya, Maryam. 1999. Women, Work and Islamism: Ideology and Resistance in Iran. London: Zed Books

- ↩ Hoominfar, E., & Zanganeh, N. (2021). The brick wall to break: women and the labor market under the hegemony of the Islamic Republic of Iran. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 23(2), 263-286.

- ↩ 8.

- ↩ Hoominfar, E., & Zanganeh, N. (2021). The brick wall to break: women and the labor market under the hegemony of the Islamic Republic of Iran. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 23(2), 263-286.

- ↩ women.ncr-iran.org

- ↩ Sahraoui, Hassiba Hadj. 2015. “Iran: Proposed Laws Reduce Women to ‘Baby Making Machines’ in Misguided Attempts to Boost Population.” Amnesty International, March 11. Accessed December 16, 2020.

- ↩ Hoominfar, E., & Zanganeh, N. (2021). The brick wall to break: women and the labor market under the hegemony of the Islamic Republic of Iran. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 23(2), 263-286.

- ↩ Nomani, Farhad, and Sohrab Behdad. 2006. Class and Labor in Iran: Did the Revolution Matter? Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- ↩ meidaan.com

- ↩ www.human-rights-iran.org

- ↩ www.akhbar-rooz.com