Lennox Hinds, whose vision has inspired and led the International Association of Democratic Lawyers and the National Conference of Black Lawyers for decades, received the 2022 Law for the People award from the Lawyers Guild. Lennox has had a storied career of his own. I mention him because, in his acceptance speech, he paid homage to George Crockett, who went from Detroit to New York to defend him against a bar complaint that threatened his license. His story shows how we all stand on the shoulders of those who have bone before. Lennox had said that a particular judge lacked the perspective and experience to be fair to a particular black litigant, a statement that aroused the ire of the New York State bar. Rather than simply going to the bar and apologizing, as many urged him to do, Lennox stood by his statement and Crockett, as was his wont, came to his defense.

George Crockett and Ernie Goodman formed the country’s first integrated law firm. Both are legends and, each in their own way, models for what it means to be a radical lawyer, engaged in battle always on the enemy’s turf. As a past Guild president, Paul Harris, said of the NLG, if we lose today, we’ll be back tomorrow. If we win today, we’ll be back tomorrow. George Crockett and Ernie Goodman exemplified that spirit and that commitment. A Goodman biography, The Color of Law: Ernie Goodman and the Struggle for Labor and Civil Rights was published in 2010 and reviewed in this journal in Vol. 68-1 by Arn Kawano. We now have, as it were, the bookend to that biography with one of Crockett, No Equal Justice: The Legacy of Civil Rights Icon George W. Crockett, JR. Edward J. Littlejohn and Peter J. Hammer.

Goodman rose to eminence primarily from the labor movement. He represented sit-down strikers at Ford in the 1930’s. Until Walter Reuther became president of the United Auto Workers in 1946 and purged those he thought were too close to the Communist Party, he represented the UAW.

Crockett’s consciousness, on the other hand, was more that of a black man who grew up in the Jim Crow south and said,

Racism pervades every area and facet of American life. It is a characteristic of American life; and hence, it is a characteristic of American law.

But their two backgrounds melded. Crockett was the grandson of an enslaved African descendant but the son of a union father, a skilled carpenter and member of the Black Carpenters Union. His commitment to justice generally and particularly for workers, both black and white, animated him even as his principal focus was race. Goodman’s vision recognized the significance of the Civil Rights Movement in the south and, under his leader- ship and not without opposition, the Guild’s emphasis shifted from union side advocacy with the formation of the Committee to Assist Southern Lawyers and the opening of an office in Mississippi to further the work. In many ways, the law firm they opened together recognized that capitalism in the United States was based both on the exploitation of all workers and the particularly cruel and lasting effects of its development on enslaved Africans and their descendants. Parenthetically, neither book mentions how either Crockett or Goodman viewed the theft of native land, certainly another special aspect of U.S. capitalism. While descendants of enslaved Africans were considered “Negro” if they had a single black grandparent—thus expanding the numbers to be subjected to super-exploitation as workers—indigenous people had to be nearly “full-blooded” because the fewer there were, the more land could be stolen.

But, this is supposed to be a review of the book about George Crockett. Why, you ask, all the prologue and why don’t you get to it.

The closest the U.S. has come to fascist rule was the McCarthy period. Communists, alleged Communists, Communist sympathizers and those who defended the right of Communists to espouse their ideas were shunned, persecuted, imprisoned and driven to suicide. The Lawyers Guild, virtually alone among legal organizations, refused to inquire as to the affiliations of its members and was willing to defend actual Communists, not just those they felt were wrongly accused of being Communists. We are today facing a similar crisis. In some ways, it may be even more dire. The Supreme Court with its reactionary majority is slashing rights won through decades, if not centuries, of struggle and sacrifice. What is hailed as “democracy” in this country is whittled down with every opinion in every term. The wealth that neoliberals claimed would “trickle down” with a growing economy in fact has siphoned up and political power and influence goes to the highest bidders. The question is whether to hunker down and accept this or to take up (at least figurative) arms against this sea of trouble and, by opposing, seek to end it. Crockett chose to do the latter. He did not win every battle. He spent four months in jail for contempt of court for being a vigorous advocate for his clients in the wake of United States v. Dennis. His and his co-counsels’ bar licenses were threatened for their alleged contempt. But, with these threats and attacks, his career did not collapse. On the contrary, he eventually was elected a judge and later a member of Congress. His career demonstrates that resistance is not always futile. An old friend of mine, David Rein, was a Guild lawyer in Washington, DC during the McCarthy era. Unlike many others, but much like Crockett, he did not shrink from facing the necessity of resistance, even with FBI agents outside his door every morning. When people told him, after the fact, what a hero he was, he scoffed. So far as he was concerned, he was only doing what was to be expected. His response to those who praised his heroism:

I’m not a hero, you’re a stinker.

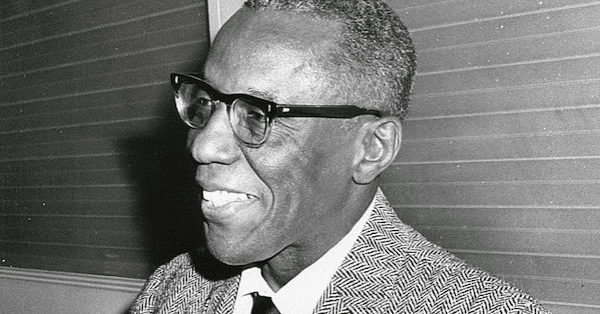

Crockett exemplified this attitude. One gets the feeling he did not concern himself with risks when he took on controversial cases. Rather, he did what he did out of principle and, therefore, could not do otherwise. He graduated from a top law school, the University of Michigan, but when he took the Florida bar exam in 1934, which was given in the Florida State Senate chamber, he was forced to sit in a chair outside the chamber because it was inconceivable to the examiners that he be allowed to sit in a senator’s seat. His response to that indignity was not to worry about it, but not to forget it and to develop the skills to do something about it. His experiences led him to his principles, but such principles are not necessarily universal. Eugene Debs said, “When I rise, it will be with the ranks, not from them.” While many aspire to rise from the ranks, Crockett remained true to the ranks of oppressed blacks and other targets of state repression and devoted his career to securing their rights.

The book itself chronicles critical events in Crockett’s life chronologically, briefly covering his roots, his law school days and his work with the Department of Labor. But the vast bulk of his work was after he moved to Detroit to take a position with the United Auto Workers and, after he and Goodman lost their jobs there, opening their law firm, which handled one landmark case after another. The accounts of those cases are what makes the book compelling. Its heart is devoted to the Dennis case and its aftermath. In the midst of anti-Communist hysteria, Dennis and his ten co-defendants, all Communist Party leaders, were charged with plotting to overthrow the government of the United States only because of what they said and what their “philosophy” was. All were convicted and their convictions affirmed. It may not be a coincidence that the Supreme Court’s decision in Dennis was effectively overruled when a Klansman, Clarence Brandenburg, was charged with, and convicted of, advocating violence in violation of Ohio state law. The Supreme Court found that Brandenburg’s speech, if inflammatory, was protected by the First Amendment, long after Dennis, his co-defendants served their sentences and their lawyers served theirs for con- tempt of court and then had to fight to keep their bar licenses.

The story of the Committee to Assist Southern Lawyers has many facets. The Color of Law told it from Goodman’s perspective. This book, telling it from Crockett’s perspective, provides a more complete, and much needed, history of the NLG’s pivot to the south and the Civil Rights Movement. It was that movement that began the resurgence of the Guild after its near disintegration in the face of McCarthyism. In no small measure, the Guild is what it is today and, indeed, may very well exist today, because of its support for that movement. The late John Lewis, in his memoir, Walking With the Wind, recalls that more traditional civil rights organizations warned SNCC not to associate with the Guild but that only the Guild responded to the call for assistance. He said the same to Michael Avery, who was then NLG president, when he was asked and agreed to deliver the keynote to the Birmingham convention.

Charles Hamilton Houston famously said a lawyer is either a social engineer or a parasite on society. Crockett was a very much a lawyer who had faith in the power of the law to engineer progressive social change. His career reflected the former of Houston’s alternatives. Others may question this belief, but Crockett surely demonstrated that lawyers on the right side of history can make a difference. The authors, both academics, try to make Crockett’s story accessible for any reader, not just for lawyers and intellectuals and it is because his life and career had such an impact on the social and political struggles of his times that it is an important story for us all and not just for lawyers.

The authors, both law professors do their best to avoid the argots of law and academia and are increasingly successful over the course of the book. The early chapters are slow to get through, but when the story gets to recounting Crockett’s exploits, the importance of his life shines through. The choice to focus on just a few, Dennis and the Civil Rights Movement in the south and his handling of the New Bethel Baptist Church incident as a judge (if you want to know more about that, you will have to read the book), is more than enough to demonstrate his intellect, his steadfastness and just how consequential a fighter for justice he was.

The book concludes with a chapter on his being a member of Con- gress from a safe seat, which left him free to act on principle without regard to politics or trade-offs. It is no surprise then that one of his first acts as a member of Congress was to sue then-President Ronald Reagan for violating the War Powers Resolution by sending soldiers to act as “advisers” to the government of El Salvador (he was represented by the Center for Constitutional Rights). His time in Congress was more a fitting coda to a life of struggle than a new chapter or direction. He ran, evidently, because he had become bored with retirement and wanted something to do. Crockett was not one to rest on his laurels and enjoy his later years sleeping late and sip- ping daiquiris. He was, to the end, a fighter for justice. Thus, we end where we began. The biography of Ernie Goodman was a necessary and important account of an important life, but it was incomplete without a biography of George Crockett, his partner in the first integrated law firm this country had seen. One must say of the formation of the firm in 1946, it was about time. One can say the same thing about No Equal Justice.

David Gespass has been on the editorial board of the National Lawyers Guild Review for over twenty-years including several years as Editor in Chief. He is a past president of the National Lawyers Guild. David is doing his best to retire from the active practice of law with only moderate success.