In early-February 2023, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) had informed Congress that China now has more launchers for Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) than the United States. The report is the latest in a serious of revelations over the past four years about China’s growing nuclear weapons arsenal and the deepening strategic competition between the world’s nuclear weapon states. It is important to monitor China’s developments to understand what it means for Chinese nuclear strategy and intensions, but it is also important to avoid overreactions and exaggerations.

First, a reminder about what the STRATCOM letter says and does not say. It does not say that China has more ICBMs or warheads on them than the United States, or that the United States is at an overall disadvantage. The letter has three findings (in that order):

- The number of ICBMs in the active inventory of China has not exceeded the number of ICBMs in the active inventory of the United States.

- The number of nuclear warheads equipped on such missiles of China has not exceeded the number of nuclear warheads equipped on such missiles of the United States.

- The number of land-based fixed and mobile ICBM launchers in China exceeds the number of ICBM launchers in the United States.

It is already well-known that China is building several hundred new missile silos. We documented many of them (see here, here and here), as did other analysts (here and here). It was expected that sooner or later some of them would be completed and bring China’s total number of ICBM launchers (silo and road-mobile) above the number of U.S. ICBM launchers. That is what STRATCOM says has now happened.

STRATCOM ICBM Counting

The number of Chinese ICBM launchers included in the STRATCOM report to Congress was counted at a cut-off date of October 2022. It is unclear precisely how STRATCOM counts the Chinese silos, but the number appears to include hundreds of silos that were not yet operational with missiles at the time. So, at what point in its construction process did STRATCOM include a silo as part of the count? Does it have to be completely finished with everything ready except a loaded missile?

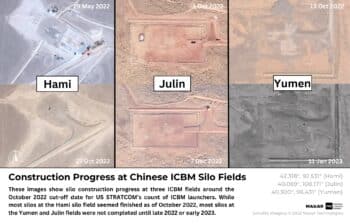

We have examined satellite photos of every single silo under construction in the three new large missile silo fields (Hami, Julin, and Yumen). It is impossible to determine with certainty from a satellite photo if a silo is completely finished, much less whether it is loaded with a missile. However, the available images indicate it is possible that most of the silos at Hami might have been complete by October 2022, that many of the silos at the Yumen field were still under construction, and that none of the silos at the Julin (Ordos) fields had been completed at the time of STRATCOM’s cutoff date (see image below).

Commercial satellite images help assess STRATCOM claim about China’s missile silos.

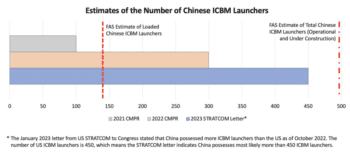

The number of Chinese ICBM launchers reported by the Pentagon over the past three years has increased significantly from 100 launchers at the end of 2020, to 300 launchers at the end of 2021, to now more than 450 launchers as of October 2022. That is an increase of 350 launchers in only three years.

To exceed the number of U.S. ICBM launchers as most recently reported by STRATCOM, China would have to have more than 450 launchers (mobile and silo)— the U.S. Air Force has 400 silos with missiles and another 50 empty silos that could be loaded as well if necessary. Without counting the new silos under construction, we estimate that China has approximately 140 operational ICBM launchers with as many missiles. To get to 300 launchers with as many missiles, as the 2022 China Military Power Report (CMPR) estimated, the Pentagon would have to include about 160 launchers from the new silo fields—half of all the silos—as not only finished but with missiles loaded in them. We have not yet seen a missile loading—training or otherwise—on any of the satellite photos. To reach 450 launchers as of October 2022, STRATCOM would have to count nearly all the silos in the three new missile silo fields (see graph below).

The point at which a silo is loaded with a missile depends not only on the silo itself but also on the operational status of support facilities, command and control systems, and security perimeters. Construction of that infrastructure is still ongoing at all the three missile silo fields.

Pentagon estimates of Chinese completed ICBM launchers appear to include hundreds of new silos at three missile silo fields.

It is also possible that the number of launchers and missiles in the Pentagon estimate is less directly linked. The number could potentially refer to the number of missiles for operational launchers plus missiles produced for launchers that have been more or less completed but not yet loaded with missiles.

All of that to underscore that there is considerable uncertainty about the operational status of the Chinese ICBM force.

However—in time for the Congressional debate on the FY2024 defense budget—some appear to be using the STRATCOM letter to suggest the United States also needs to increase its nuclear arsenal.

Comparing The Full Arsenals

The rapid increase of the Chinese ICBM force is important and unprecedented. Yet, it is also crucial to keep things in perspective. In his response to the STRATCOM letter, Rep. Mike Rogers—the new conservative chairman of the House Armed Services Committee—claimed that China is “rapidly approaching parity with the United States” in nuclear forces. That is not accurate.

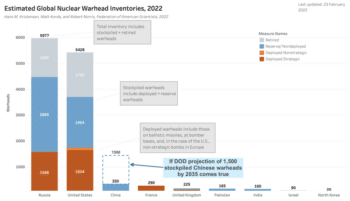

Even if China increases it nuclear weapons stockpile to 1,500 by 2035, it will only make up a fraction of the much larger U.S. and Russian stockpiles.

Even if China ends up with more ICBMs than the United States and increases its nuclear stockpile to 1,500 warheads by 2035, as projected by the Pentagon, that does not give China parity. The United States has 800 launchers for strategic nuclear weapons and a stockpile of 3,700 warheads (see graph below).

The worst-case projection about China’s nuclear expansion assumes that it will fill everything with missiles with multiple warheads. In reality, it is unknown how many of the new silos will be filled with missiles, how many warheads each missile will carry, and how many warheads China can actually produce over the next decade.

The nuclear arsenals do not exist in a vacuum but are linked to the overall military capabilities and the policies and strategies of the owners.

The Political Dimension

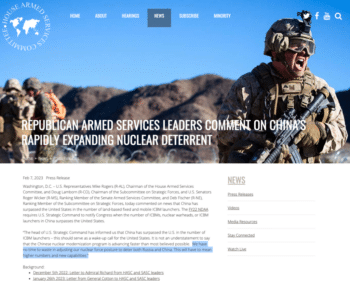

STRATCOM initially informed Congress about its assessment that the number of Chinese ICBM launchers exceeded that of the United States back in November 2022. But the letter was classified, so four conservative members of the Senate and House armed services committees reminded STRATCOM that it was required to also release an unclassified version. They then used the unclassified letter to argue for more nuclear weapons stating (see screen shot of Committee web page below):

We have no time to waste in adjusting our nuclear force posture to deter both Russia and China. This will have to mean higher numbers and new capabilities. (Emphasis added.)

Lawmakers immediately used STRATCOM assessment of Chinese ICBM launchers to call for more U.S. nuclear weapons.

Although defense contractors probably would be happy about that response, it is less clear why ‘higher numbers’ are necessary for U.S. nuclear strategy. Increasing U.S. nuclear weapons could in fact end up worsening the problem by causing China and Russia to increase their arsenals even further. And as we have already seen, that would likely cause a heightened demand for more U.S. nuclear weapons.

We have seen this playbook before during the Cold War nuclear arms race. Only this time, it’s not just between the United States and the Soviet Union, but with Russia and a growing China.

Even before China will reach the force levels projected by the Pentagon, the last remaining arms control treaty with Russia—the New START Treaty—will expire in February 2026. Without a follow-on agreement, Russia could potentially double the number of warheads it deploys on its strategic launchers.

Even if the defense hawks in Congress have their way, the United States does not seem to be in a position to compete in a nuclear arms race with both Russia and China. The modernization program is already overwhelmed with little room for expansion, and the warhead production capacity will not be able to produce large numbers of additional nuclear weapons for the foreseeable future.

What the Chinese nuclear buildup means for Chinese nuclear policy and how the United States should respond to it (as well as to Russia) is much more complicated and important to address than a rush to get more nuclear weapons. It would be more constructive for the United States to focus on engaging with Russia and China on nuclear risk reduction and arms control rather than engage in a build-up of its nuclear forces.

Additional Information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces