The U.S. government reached its debt limit of $31.4 trillion in early 2023. This unleashed a deluge of debate as to whether or not the Treasury was going to default, and how a deeply divided Congress could come to an agreement to raise the debt ceiling.

The constant chatter in the mainstream corporate media overlooked the real controversy, however. The reality is that practically no one in Washington truly cares about the U.S. national debt.

In fact, in a bipartisan deal negotiated in late May to raise the debt ceiling, Democratic President Joe Biden and Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy agreed not to cut but rather to increase the already massive military budget from roughly $800 billion to $886 billion.

At the same time, the Biden-McCarthy deal makes it more difficult for poor people in the United States to get access to food stamps and welfare.

The U.S. debt ceiling is a manufactured problem. It is a political football that is used every few years to justify cutting government funding for the very few social programs that do exist.

U.S. public debt is denominated in dollars. It is money that the government could print and pay off.

Doing so would certainly fuel inflation. (And given the status of the dollar as the global reserve currency, that inflation would be exported to other countries as well.) But the U.S. government has a precedent for doing so.

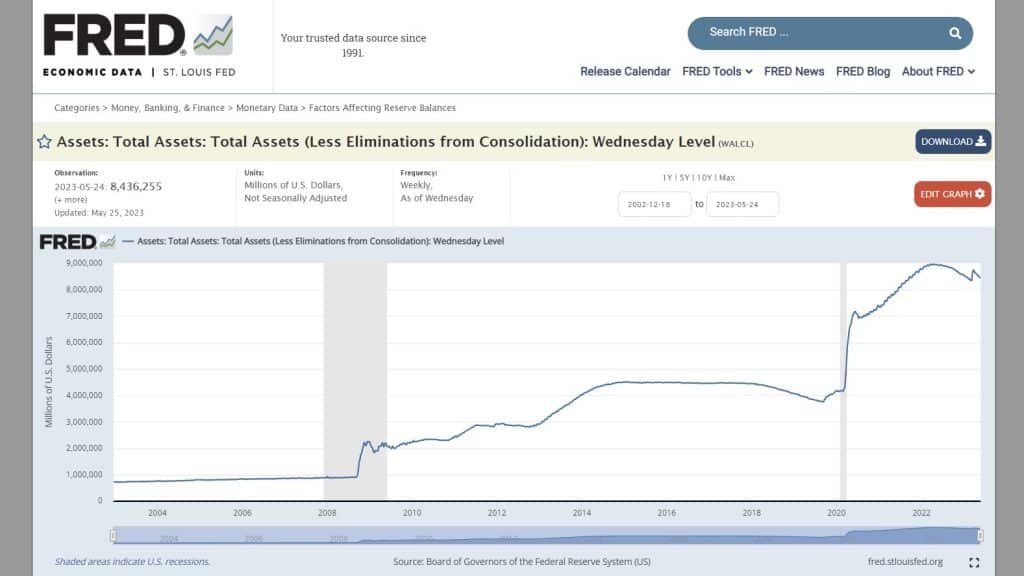

The U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, effectively printed $8 trillion from 2008 until 2022, over 14 years of quantitative easing, to inflate an enormous asset bubble that made the rich even richer.

Unlike the United States, however, many foreign countries, especially those in the Global South, cannot simply print money to pay off their debts. Their monetary sovereignty is heavily restricted.

The government debt of many Global South nations is denominated in foreign currencies, primarily the U.S. dollar. Yet they can’t print U.S. dollars; only Washington can do so.

This has left countries like Argentina trapped in odious debt, denominated largely in U.S. dollars, that is essentially unpayable, fueling an inflation crisis—and giving rise to fascistic, far-right demagogues.

Many countries hold national debt denominated in dollars because the greenback is the global reserve currency.

So the United States can maintain a gargantuan trade deficit with the world, sucking in the surplus produced by foreign workers, racking up trillions in debt, but its money doesn’t significantly devalue because there is so much international demand for it. And wealthy elites across the planet hold much of their wealth in dollar-denominated assets—like the Treasury securities that make up the national debt.

This is the exorbitant privilege of the U.S. dollar.

Both U.S. political parties agree with Dick Cheney: ‘Deficits don’t matter’

It is clear that virtually no one in Washington actually believes that the debt ceiling is important, because the vast majority of the members of both hegemonic political parties happily vote every year to keep increasing the military budget—which is on the path to reach $1 trillion by 2030.

Back in the 2000s, when Republican George W. Bush was president, his neoconservative Vice President Dick Cheney boasted that “deficits don’t matter”.

Cheney approvingly cited the previous Republican president from the 1980s, lecturing Bush’s Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill: “You know, Paul, [Ronald] Reagan proved deficits don’t matter“.

The Bush administration further proved this by spending trillions of dollars to wage the so-called “war on terror”. Washington invaded Afghanistan, then invaded Iraq, while expanding the U.S. military’s footprint all around the world.

Where did the trillions of dollars needed to wage those wars come from? The government just spent it. It didn’t care about the debt ceiling, because Washington can create dollars—something no other country in the world can do.

The deal between President Biden and House Speaker McCarthy reflects the same logic shared by Cheney.

Debt ceiling bill reflects the bipartisan consensus in Washington: cut social spending to further enrich military contractors pic.twitter.com/l1RSjXBxDf

— Stephen Semler (@stephensemler) June 1, 2023

While Republicans on the floor of the Congress demanded that Washington impose austerity measures, they eagerly joined Democrats in increasing the military budget from around $800 billion in 2023 to $886 billion in 2024.

(Many major media outlets reported that the agreement boosted U.S. military spending to $885 billion, but the precise number is $886.3 billion.)

Bloomberg reported clearly on this hypocrisy:

Republican lawmakers who oppose the debt-ceiling bill argue it doesn’t do enough to cut spending or reduce the deficit. Yet when defense is concerned, many argue the government ought to be spending more, not less.

Under the deal passed by the House on Wednesday evening [May 31] and sent to the Senate, defense spending would get the 3.3% increase the president proposed for the coming year–even as other programs are cut.

…

The administration’s $886.3 billion national security budget request for fiscal 2024 provides the biggest-ever defense spending increase and also one of the largest peacetime budgets when adjusted for inflation.

The U.S. would be spending more on defense than the next 10 nations combined.

However, even these staggering official figures are an underestimate.

The Congressional Budget Office divides U.S. discretionary spending between “defense” and “nondefense”.

In 2023, “defense” expenditure was reported as roughly $800 billion, with “nondefense” as $936 billion. But those figures are misleading, because the so-called nondefense spending included $131 billion of benefits for military veterans.

So if you subtract veterans’ benefits from nondefense and add it to defense, military expenditure was at least $931 billion, or 54.5% of 2023 discretionary spending.

This is just the official discretionary spending on paper. In reality, the U.S. military frequently spends much more. The Pentagon has failed every single audit it has ever tried, and there are tens of trillions of dollars of spending that is completely unaccounted for.

The point is that the approximately $800 billion military budget in 2023 was already an underestimate, which suggests that the new $886.3 billion that Biden and McCarthy agreed on for 2024 is likely a lowball as well.

Meanwhile, U.S. military spending is off the charts, when compared to other countries.

In 2022, US military expenditure made up 39% of global spending. Washington spent 10 times more on its military than Russia, and three times more than China (despite the fact that China has four times the U.S. population).

US military spending in 2022 was actually estimated at $877 billion (significantly higher than the official discretionary budget). That was larger than the next 10 biggest military spenders combined.

So Washington spent more on its military than China, Russia, India, Saudi Arabia, Britain, Germany, France, South Korea, Japan, and Ukraine, all together. And many of those countries are U.S. allies.

US military spending was higher than the next 10 countries combined in 2022. Five years ago, it was higher than only the next nine. How much safer do y’all feelhttps://t.co/VIq8pwChRI pic.twitter.com/FX47O8Uego

— Stephen Semler (@stephensemler) April 29, 2023

In short, this bipartisan agreement in which the Democratic president and the Republican speaker of the House agreed to increase military spending to (a minimum of) $886 billion makes it very clear that both corporate parties in the United States recognize that the national debt is not a real problem. They agree with Dick Cheney: “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter”.

Washington restricts food stamps and welfare

While increasing the military budget, the Biden-McCarthy deal simultaneously makes it more difficult for poor people in the United States to receive food stamps and welfare.

The agreement states that people aged 54 and under have to work at least 80 hours a month in order to receive food stamps.

This deal could potentially push hundreds of thousands of people in the United States off of receiving food stamps and welfare.

This is despite the fact that these social support programs have already been significantly slashed.

Former President Bill Clinton campaigned on the promise that he would “end welfare as we know it”, and he basically did so.

Donald Trump also tried to significantly cut food stamps. (Although a court blocked his plan.)

Hunger is a serious problem in the United States. A 2020 report by the Brookings Institution found that more than 16% of households with children did not have enough food. That was one out of six children.

The food stamp program is officially known as SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

According to data from the Department of Agriculture, four-fifths (81%) of U.S. households that receive SNAP have either a child, an elderly individual, or an individual with a disability.

In 2022, one-fifth of children in the U.S. lived in families that received food stamps.

As of February 2023, 42.5 million people in the U.S. received food stamps. That is 13% of the U.S. population: more than one out of every 10 people.

This is a vitally important social program, because poverty remains a very significant problem in the United States. This is painfully visible with the growing homelessness in major cities.

Meanwhile, inequality is increasing; billionaires and millionaires keep getting wealthier; the rich get richer and the poor are getting poorer.

As president, Donald Trump oversaw $1.5 trillion in tax cuts. A 2019 study found that these resulted in billionaires paying a lower tax rate than the bottom half of U.S. households.

“In 2018 the richest 400 families in the U.S. paid an average effective tax rate of 23% while the bottom half of American households paid a rate of 24.2%”, The Guardian reported.

The newspaper added, “Taxes on the rich have been falling for decades. In 1960 the 400 richest families paid as much as 56% in taxes, by 1980 the rate had fallen to 40%”.

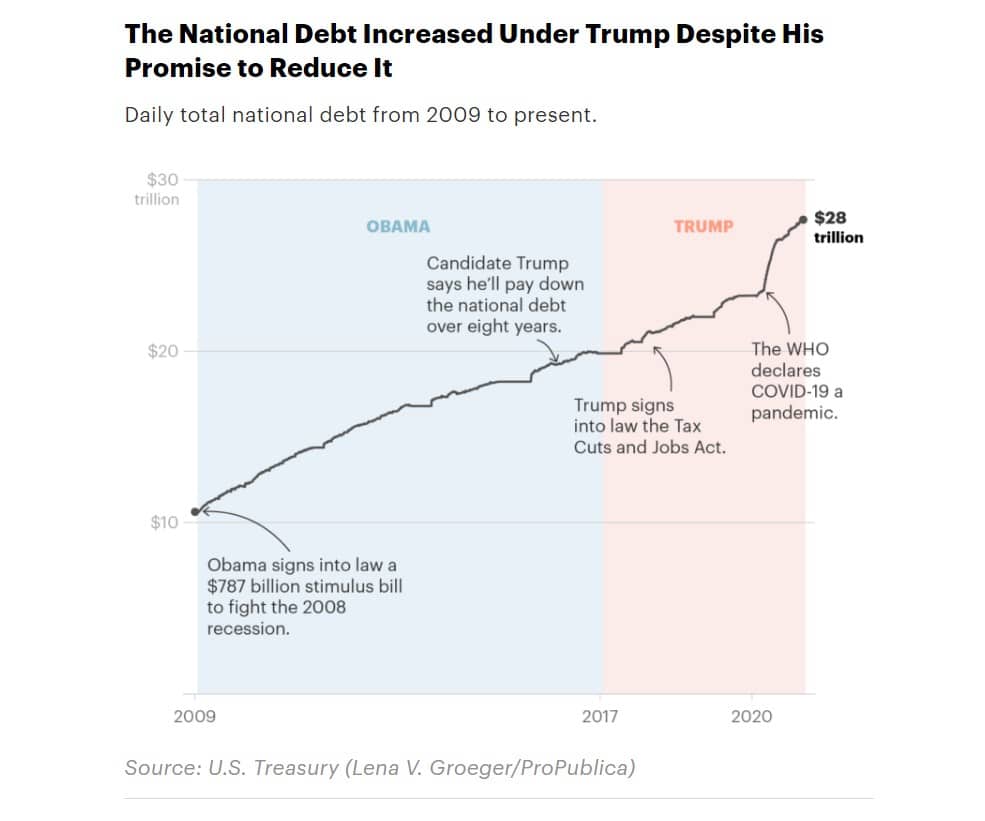

When he ran for office in 2016, Trump had outlandishly claimed he would pay off the U.S. national debt within eight years.

Instead, the national debt rose by nearly $7.8 trillion during Trump’s four years in office.

“The growth in the annual deficit under Trump ranks as the third-biggest increase, relative to the size of the economy, of any U.S. presidential administration”, ProPublica reported.

It is very easy to explain why there is such a massive national debt in the United States: The rich pay fewer and fewer taxes (while the tax burden actually is increasing on poor and working people); and the U.S. government has spent trillions of dollars waging wars around the world, maintaining 800 foreign military bases and launching 251 foreign military interventions just since 1991, according to data from the Congressional Research Service.

Moreover, for more than a decade, the U.S. Federal Reserve ran what was effectively a free money program for the rich, printing some $8 trillion to pump up one of the largest asset bubbles in human history, inflating the prices of stocks, bonds, and real estate.

These assets are owned by rich people, not the poor. It was trillions of dollars going into the pockets of the richest people in the United States—and into those of elites in other parts of the world.

This was the most massive act of welfare in human history. Welfare for the rich.

Following the 2008 financial crash, in 14 years of quantitative easing, the Fed “printed” (digitally, at least) trillions of dollars to buy up treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, including toxic assets that practically no one wanted to invest in.

Who were the beneficiaries? The rich. Because in the United States, the wealthiest 10% of people own nearly 90% of stocks.

The insult to injury is that, while Washington was pouring money into this substantial welfare for the rich, it was cutting the paltry welfare for the poor.

US imperialism and the dollar’s exorbitant privilege

The last detail that is ignored in mainstream media discussion of the U.S. debt ceiling is the role of the dollar as the global reserve currency.

Many economists from the school of modern monetary theory (MMT) have noted that the debt ceiling is an arbitrary, manufactured scandal, because it is debt that the U.S. government owes in dollars.

If the government wanted, it could simply print that money to pay off the debt. It would create inflation, but it would be possible.

But few MMT proponents acknowledge the fact that this is only really possible in the United States because of its unique status as the issuer of the global reserve currency, and its role at the center of the imperialist world system.

One of the very few economists who has explained this is Michael Hudson. His book Super Imperialism shows how the international financial system was essentially designed to give the United States a free lunch.

Most governments around the world, especially in the Global South, cannot simply print money in order to pay off their debt, because much of it is denominated in a foreign currency, commonly dollars.

For many countries in the Global South, when the government needs finance, it will sell eurobonds—government debt denominated in a foreign currency. (Despite the name, a eurobond has nothing to do with the euro.)

When these Global South nations—like, say, Ghana, Zambia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, or Argentina—sell eurobonds denominated in U.S. dollars, their economies have to actually produce value in order to get access to those dollars to pay off their debt.

When they import crucial commodities like oil and gas, capital goods like machine parts and vehicles, or other technologies, they need dollars to pay for them (lest they risk a local currency devaluation).

The U.S. economy does not have to produce anything of value. Washington can simply print the dollars needed to pay off its debts or import foreign goods and services.

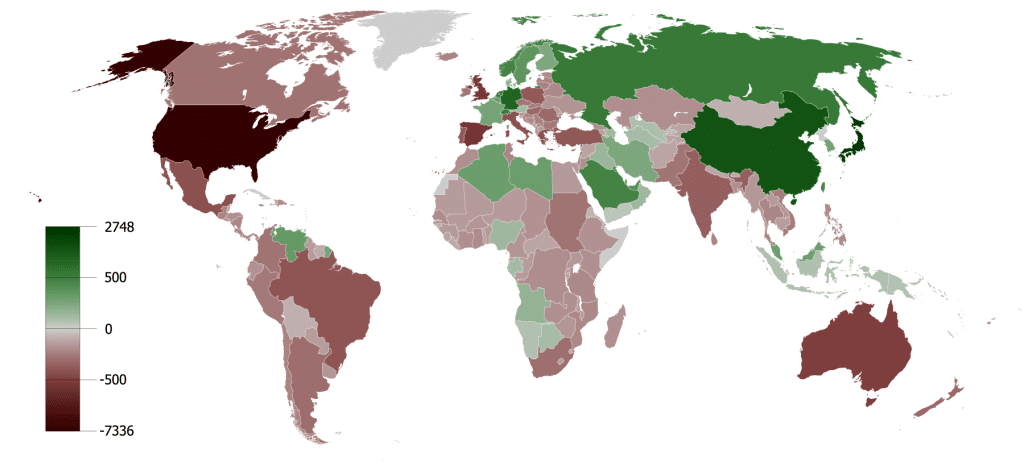

This is precisely how the United States has maintained the world’s largest current account deficit for decades.

This means that the U.S. government consistently imports way more than it exports, and at a level that no other country on Earth can come close to.

Countries by their current account balance, averaged from years 1980 to 2008 (red is a deficit, green is a surplus)

In addition to its massive trade deficit with the rest of the world, there is a massive inflow of investments into securities in the United States, leading to a capital account surplus. (The inverse of the current account is the capital account.)

Argentina also frequently has a current account deficit. It largely exports cheap, low value-added agricultural goods, while importing energy, high value-added capital goods, and technologies.

This has led to a severe devaluation of Argentina’s currency, the peso. Triple-digit inflation is eroding away the life savings and living standards of Argentine workers.

The U.S. current account deficit is much larger than Argentina’s, but Washington’s debt is denominated in dollars, which it can print; Buenos Aires’ debt is also mostly denominated in dollars, which it cannot print.

Argentina is unable to pay the massive debt it owes in dollars, largely to Western vulture funds like BlackRock and to the U.S.-dominated International Monetary Fund (IMF), and its central bank is thus constantly bleeding foreign exchange reserves in an attempt to service debt payments, pushing the peso into freefall.

That is a fundamental difference between the U.S. and Argentina.

When most countries have a consistent current account deficit, their national currencies are devalued. They have to sell their currency in foreign exchange markets in order to get access to the foreign currencies they use to buy the excess imports.

Because of the hegemony of the U.S. dollar, because of the design of the U.S.-centered imperialist world system, that means they usually have to get access to dollars.

So the Argentine peso has significantly weakened in relation to the U.S. dollar.

When countries with chronic current account deficits see their currencies devalued, it decreases the living standards and purchasing power of workers, often making it prohibitively expensive to buy imported products like phones or computers.

But what this also does, simultaneously, is make exports in those countries more competitive, because it is now cheaper for those goods to be bought by foreign clients.

Theoretically, at least on paper, this process could thus lead the deficit country to move toward a more balanced current account over time, with a better balance of payments with other countries.

However, in the United States, the dollar does not significantly devalue, despite the massive current account deficit, because of its status as the global reserve currency: Washington’s exorbitant privilege.

Outside of Argentina, very few people want pesos. Unless you’re buying goods or services from Argentina, the currency is not useful. And even much of the invoicing for Argentina’s international trade is done in dollars. (Although that is changing as Buenos Aires and Beijing seek to de-dollarize their commercial exchange.)

Very few people outside of Argentina are investing in Argentine assets denominated in the peso. They’re using U.S. dollars.

However, because of the exorbitant privilege of the dollar, the U.S. can keep importing, and importing, and importing, absorbing the surplus of the world, sucking in the drain of the surplus value produced by foreign workers.

As for the massive flow of dollars out into the rest of the world, they are frequently invested in assets in the United States, like securities on Wall Street, or in real estate, or Treasury bonds—that is to say, the national debt!

This is the “exorbitant privilege” that France’s Finance Minister and future President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously complained about in the 1960s.

The U.S. economy doesn’t need to produce $100 worth of value, through the labor of its workers, in order to buy $100 worth of products. The U.S. government can print that money. (And it is basically free, because most of that “printing” is digital; it’s not even physical cash; it’s numbers on a computer screen on the balance sheets of the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury.)

So if the U.S. needs to rectify its balance of payments and fund imports, the Treasury can sell bonds denominated in its own currency.

On the other hand, workers in other countries, especially those in the Global South, have to produce constant surplus; they have to break their backs working in order to produce $100 worth of value to get 100 dollars.

A sizeable part of those 100 dollars then often flow immediately back out of the country to pay interest on the debt owed to vulture funds on Wall Street, to asset management firms like BlackRock, which are investing the capital of rich oligarchs and gobbling up assets around the world.

So yes, the MMT theorists are correct; the U.S. government can print dollar to pay off its national debt.

Some creative economists have proposed that the Treasury could even mint a $1 trillion platinum coin, so Congress won’t have to raise the debt ceiling in the future. That is technically possible.

However, most governments around the world cannot do this.

As for the small handful of other countries that, like the United States, have relatively stable economies but large national debts, what makes them different is they mostly have current account surpluses.

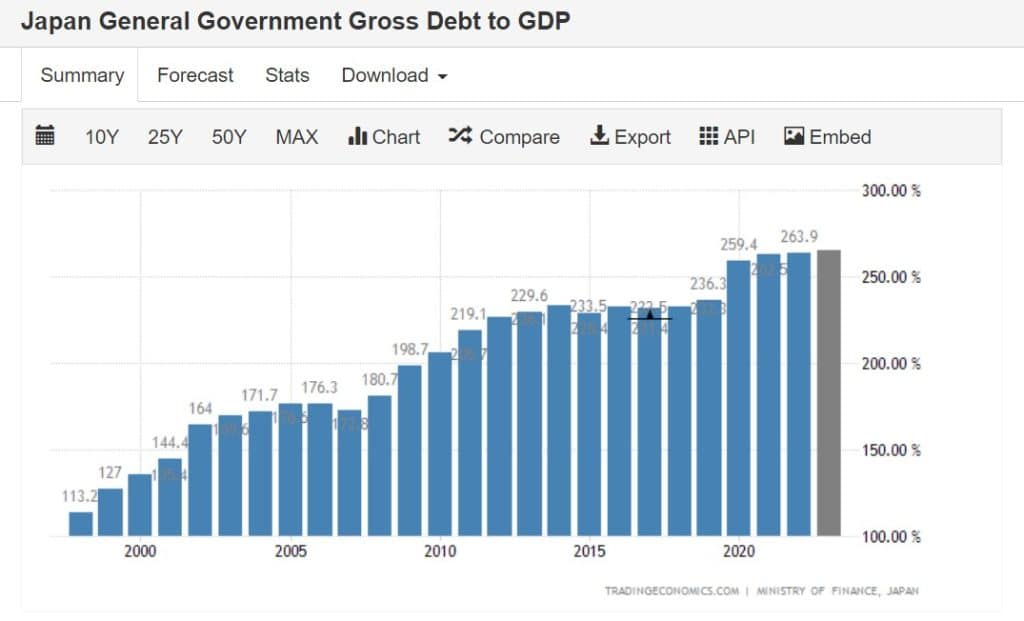

Japan, for instance, has a gargantuan national debt of over 260% of GDP (roughly double the US debt-to-GDP ratio of 130%).

However, unlike the U.S., Japan has a chronic current account surplus. It is a manufacturing powerhouse.

Moreover, like the U.S., Japan’s debt is largely denominated in its own currency, the yen, which Tokyo can print.

In fact, Japan’s central bank owned a staggering 52% of government bonds as of the end of 2022. This is national debt owed by one part of the government to another part of the government.

Even further, more than 90% of Japan’s debt was held domestically, with just 8% owed to foreigners, as of the end of 2021.

Japan is also a key part of the U.S.-led imperialist system. This is what gives Japan the economic and political ability to maintain this debt relationship and to denominate its bonds in yen, in a way that many countries cannot do.

This is particularly true for countries in the Global South that are targeted by the United States for regime change, war, sanctions, and economic blockades.

These nations are heavily restricted in their options for getting access to finance, which is needed to build infrastructure and develop the economy.

Very few investors are going to buy the debt of a country under U.S. sanctions, of a nation facing the prospects of external destabilization and war—which would mean they probably wouldn’t get paid back for their investment.

The point of all of this is that the relative “unimportance” of the U.S. national debt, as acknowledged by Dick Cheney and many MMT theorists alike, is largely a product of its position at the center of the imperialist world-system of global accumulation.

If you are a poor country in the Global South, yes, you can print more and more of your currency to pay for social programs, but if that is not matched by corresponding economic activity and growth, if there is not a demand for your currency for importing the products that your economy produces, and especially if your country is dependent on importing commodities and capital goods, it is likely going to lead to significant inflation, which could devastate your economy.

The final factor to emphasize is the sheer, blunt force of the U.S. military, with its nearly trillion-dollar annual budget and 800 foreign bases.

If Washington simply decided to default one day, and refused to pay its foreign debts, no foreign power could invade the U.S. and force it to do so. The same cannot be said for most other countries, especially small ones with few resources in the periphery of the imperialist world system.