Anti-government protester during 2018 coup attempt in Nicaragua. Numbers of the protesters were tied to groups that had received funding from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). [Source: yahoo.com]

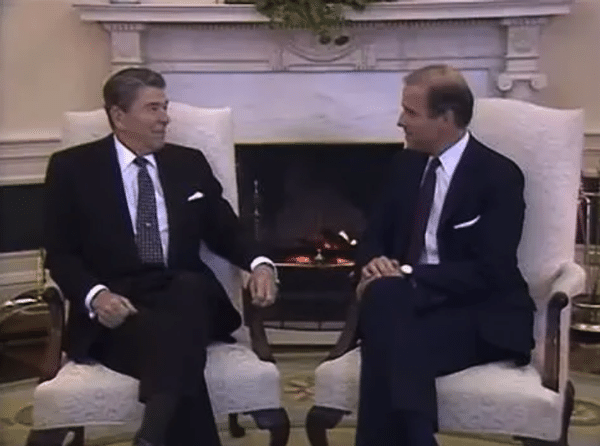

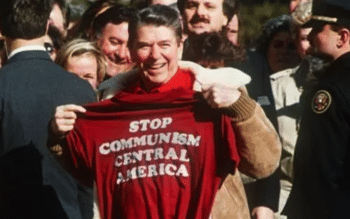

During the 1980s, the American left was mobilized in opposition to the Reagan administration policy of arming the Nicaraguan Contras—counter-revolutionaries, whose primary purpose was to destabilize the left-wing Sandinista government.

The Sandinistas had led a 1979 revolution against the corrupt Somoza dynasty that had long been backed by the U.S. and won fair elections in 1984 that the U.S. had tried to sabotage.

Idealistic young people during the 1980s protested against U.S. policy and traveled on peace delegations to Nicaragua that displayed solidarity with the Sandinistas who were trying to uplift the Nicaraguan population and build a better society.

Four decades later, the Sandinistas are starting to make good on their pledge. Since they regained power in 2007, they have reduced poverty considerably, ensured Nicaragua’s food sovereignty, cut down illiteracy, and advanced women’s rights.

Much vilified in the U.S., Nicaragua President Daniel Ortega was imprisoned for seven years in the 1970s, during the Sandinistas’ struggle against the Somoza dictatorship, and has popularity ratings that are at least double those of U.S. President Joe Biden.

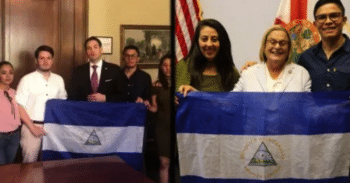

MRS leader Ana Margarita Vijil (3rd from right), lobbying Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (center),

notorious right-wing U.S. Congress member, for coercive measures against Nicaragua’s government in 2016. [Source: tortillaconsal.com]

Under Ortega’s leadership, a poll found that Nicaragua was the country in the world whose people felt most at peace.1

In the summer of 2018, however, when they were faced with a violent right-wing uprising reminiscent of the Contras, much of the American left sided against Ortega and with the insurrectionists.

They bought into the official U.S. government narrative depicting Ortega as a tyrant equivalent to Somoza and the golpistas as idealists bent on democratizing Nicaragua.

CIA Footprint

Nicaraguan student leaders lobbying in 2018 for U.S. intervention, with Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Marco Rubio. [Source: tortillaconsal.com]

Curiously, the protests were led initially by students when they were supposedly triggered by Ortega’s announcement of modest changes to social security in which employers would have to pay slightly more in order to sustain promised payouts.

Why would students be so worked up by changes to benefits which they did not stand to receive until decades later or to a small increase in employer contributions? The protests intensified further after Ortega announced, very swiftly after the protests began, that he would not go forward with the announced social security changes.

With time it became clear that behind the protests were professional right-wing agitators and violent provocateurs, numbers of whom belonged to organizations that had received funding from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a CIA offshoot that spent $4.1 million in Nicaragua on 54 different projects between 2014 and 2018.2

Guarimba uprising in Venezuela (2016), which also grew violent quickly and was funded in part by U.S. government agencies such as the NED. [Source: bwcentral.org]

MRS leaders have been colluding with the U.S. government against the Sandinistas for years, working with neo-conservative members of the U.S. Congress and Miami’s regime-change lobby, all while raking in funding from U.S. interventionist organizations and providing the U.S. with intelligence about the Sandinistas, as classified State Department cables published by WikiLeaks reveal.3

As part of the regime-change operation, rumors were spread that Ortega had ordered the massacre of student demonstrators, which was not true. Many of the 200 people who were killed were police killed by the insurrectionists in Contra-style terrorist attacks in which Sandinista monuments and symbols were destroyed along with other historic buildings.

The protests bore eerie resemblance to the Guarimba uprising against socialist leader Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, which U.S. government agencies were also behind.

Biden: Smears and Ratcheting Up of Sanctions

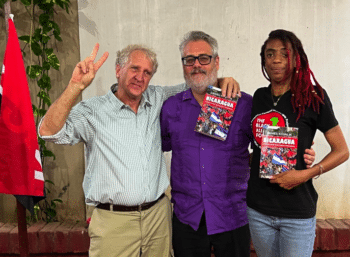

Dan Kovalik with raffle winners at book launch in Managua on July 17, 2023. [Source: Photo Courtesy of Lauren Smith]

He went on to win Nicaragua’s 2021 election so convincingly that the Biden administration referred to it as a “pantomime election” and a “sham.”

In October 2022, the Biden administration released a statement proclaiming that, in the lead-up to the election, “the Ortega-Murillo [Rosario Murillo is the First Lady and Vice President] regime arbitrarily detained dozens of political opponents and pro-democracy activists. Since then, the limited remaining democratic space in the country has shrunk even further as the Ortega-Murillo regime shuttered over 2,000 non-governmental organizations and subjected political prisoners to extremely harsh conditions.”

However, these political opponents and alleged pro-democracy activists were behind the violent 2018 insurrection, which resulted in hundreds of wounded, the burning of government buildings, and more than $1 billion in economic losses. The NGOs that were shuttered were foreign-funded ones that were also behind the coup.

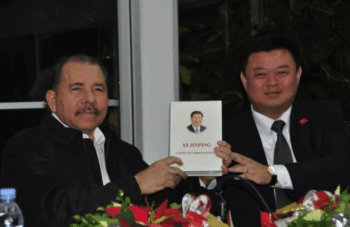

Daniel Ortega holding up a portrait of Xi Jinping with Wang Jing, a billionaire intent on funding a Nicaraguan canal. [Source: primerinforme.com]

Biden’s verbal attacks on the Ortega-Murillo regime—reinforced by the mainstream and alternative media—have been used to justify the expansion of sanctions on Nicaragua whose purposes are to paralyze and destroy Nicaragua’s economy, and bring down the government—as Ronald Reagan and the CIA had attempted in the 1980s.

The latest rounds target Nicaragua’s gold industry, which is Nicaragua’s top export, and have made it more difficult for Nicaragua to obtain international loans which it has been using to fund its progressive social programs.4

Countering the Threat of a Good Example

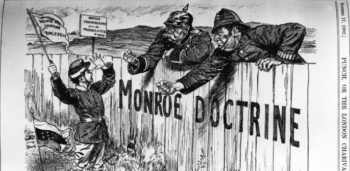

[Source: politicalcartoonproject.blogspot.com]

The main reason the Biden administration has targeted Nicaragua is because, under Ortega’s leadership, Nicaragua has adopted domestic and foreign policies independent from U.S. control that have improved living standards for Nicaraguans.5

Nicaragua in turn offers “the threat of a good example” that could very well be emulated by other countries in Latin America, which could unify against U.S. imperialism and the Washington consensus, or neo-liberal economic paradigm that has sowed vast inequality and misery.

Map with proposed canal routes. [Source: wikipedia.org]

U.S. Imperial Intervention and Nicaraguan Resistance

Kovalik points out at the beginning of his book that U.S. intervention in Nicaragua over the last one hundred plus years should be viewed in the context of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which signaled U.S. intentions to dominate Latin America and keep other European powers out, following the demise of the Spanish Empire.

According to Kovalik, despite the construction of the Panama Canal to help extradite the extraction of Latin American resources to North America, the U.S. has never given up on the possibility of developing another canal passing through Nicaragua, which would be even bigger because of Nicaragua’s giant lake which extends close to the Atlantic.

Philander C. Knox [Source: uspresidentialhistory.com]

A year later, William Walker, a physician and newspaper editor from Tennessee, backed by U.S. bankers and the Democratic Party, launched an invasion of Nicaragua from Greytown and reinstated slavery after declaring himself President of Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador.

Andrés Castro, who threw a rock that incapacitated Walker, is memorialized in a painting entitled La Pedrada (“The Stone”) by Luis Vergara Ahumada.

The next and most sustained U.S. intervention, in 1910, targeted Nicaragua’s Liberal Party President, José Santos Zelaya, who preceded the Sandinistas in seeking to develop Nicaragua for Nicaraguans, building roads, ports, railways, and more than 140 schools in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

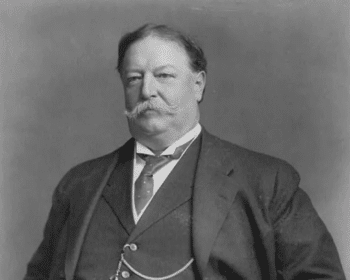

William Howard Taft [Source: serene-musings.blogspot.com]

In the summer of 1909, Knox began orchestrating a campaign—reminiscent of the contemporary one against Ortega—to turn American public opinion against Zelaya, seizing on a minor incident where an American tobacco merchant in Nicaragua was briefly jailed to paint the Nicaraguan regime as brutal and oppressive.

Soon, the media were reporting that Zelaya had imposed a “reign of terror” in Nicaragua and become the “menace of Central America.” As their sensationalist campaign reached a peak, President Taft gravely announced that the United States would no longer “tolerate and deal with such a medieval despot.”

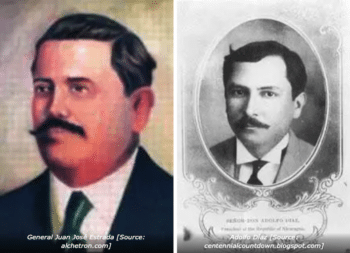

American businessmen subsequently formed a conspiracy with the ambitious provincial governor, General Juan José Estrada, who was succeeded as president by Adolfo Díaz, the chief accountant of the La Luz mining company. Díaz drained the treasury that Zelaya had built up and gave the stolen money to his corrupt cronies.6

General Juan José Estrada / Adolfo Díaz

Taft ordered U.S. Marines stationed in Panama to invade Nicaragua under the command of General Smedley Butler to preserve Díaz’s government against an insurrection led by Benjamin Zeledón, a lawyer from Jinotega and national hero who was killed in the Battle of Barrance-Coyotepe.

Butler said later that the U.S. Marine intervention was “rotten to the core,” inspired as it was by “Americans who have wildcat investments down here [Nicaragua] and want to make them good by putting in a government which will declare a monopoly in their favor.”7

Sandino Rebellion

After Zeledón’s death, the banner of resistance was picked up by Augusto César Sandino, who had worked at a gold mine owned by the U.S. in Nueva Segovia, a coffee-growing region where life expectancy at the time was only 42 years.

As a seventeen-year-old, Sandino had witnessed Nicaraguan troops parading Zeledón’s mutilated corpse in his hometown of Niquinohomo. Sandino understood that Zeledón had been killed “by bullets of Yanqui soldiers serving the interests of Wall Street.”

General Smedley Butler [Source: latinamericanstudies.org]

Sandino had refused to go along with other Liberal Party leaders—including General Moncada, then leading the Liberal rebellion against Chamorro—who were willing to sign an agreement with the Conservative Party brokered by the U.S. that would have allowed Adolfo Díaz to return to power, consented to the U.S. creation of a National Guard and allowed continued occupation by U.S. forces until the next election.

Sandino’s first attack against the U.S. occupation was symbolic, targeting the U.S.-owned San Albino gold mine, which was seen to have badly exploited its workers. The U.S. Marines responded by bombing pro-Sandino villages.

José Antonio Ucles Mann recalled decades later that “the airplanes, when they saw smoke rising, when they saw someone making food for their children, the mothers of the families, they’d bomb them, they’d kill them all. When they saw someone, it was a question of dropping bombs.”

Augusto César Sandino [Source: espino-roja.blogspot.com]

Despite the cruelty of their counterinsurgency tactics, the U.S. Marines were unable to break the resolve of the Sandinistas and left Nicaragua in 1933.

Eduardo Galeano wrote in Open Veins of Latin America that:

The epic of Augusto César Sandino stirred the world. The long struggle of Nicaragua’s guerrilla leader was rooted in the angry peasants’ demand for land. His small, ragged army fought for some years against twelve thousand U.S. invaders the National Guard. Sardine tins filled with stones served as grenades, Springfield rifles were stolen from the enemy, and there were plenty of machetes; the flag flew from the handy stick, and the peasants moved through mountain thickets wearing strips of hide called huaraches instead of boots. The guerrillas sang to the tune of Adelita: ‘In Nicaragua, the mouse kills the cat.’

U.S. soldiers sent to Nicaragua to hunt down Sandino and his supporters. [Source: pinterest.com]

Somoza and his sons would go on to rule Nicaragua for the next 45 years like a personal fiefdom, with heavy U.S. backing.9

Back to the Future

In 1961, Sandino’s heirs formed the Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN), which endured large-scale repression before finally overthrowing the last ruling Somoza (Anastasio “Tachito”) in 1979.

Kovalik points out that, in 1969, the Sandinistas put forth a complete program for the revolution, which was pluralistic and democratic, and did not resemble the cartoonish caricature of “Communism,” which the U.S. has claimed the Sandinistas espouse.10

Sandino guerrillas in 1931. Left to right: Tranquilino Jarquín, a Miskito Indian, Col. Juan Ferreti and Luis R. Aráuz. [Source: latinamericanstudies.org]

The Carter administration set the groundwork for Reagan when it began arming Nicaraguan resistance forces, which metamorphosed into the Contras.12

Former CIA officer John Stockwell gave a speech in which he said that the Contras—consisting primarily of former National Guardsmen loyal to Somoza—would routinely “go into villages, where they would haul out families and have the children watch as they castrated their father, peel off his skin, put a grenade in his mouth and pull the pin. With the children forced to watch, they gang rape the mother and slash her breasts off. And sometimes for variety, they make the parents watch while they do these things to the children.”13

One of the most infamous ways the CIA directed the Contras was through its notorious “terrorist manual,” officially called “Psychological Operation in Guerrilla Warfare,” which instructed them to “destroy military or police installations, cut lines of communications, [and] kidnap officials of the Sandinista government.” The CIA would also stage attacks against Nicaragua’s Indigenous population—the Miskito Indians—that could be blamed on the Sandinistas.14

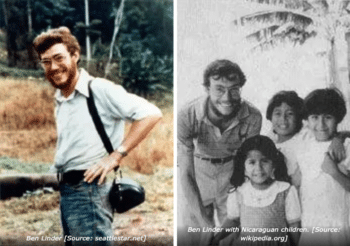

Ben Linder

The Reagan administration’s covert support for the Contras bore fruit in 1990 when Nicaraguans were intimidated into voting out the Sandinistas—as they did not want to invite further foreign intervention and wanted the lifting of a harsh economic embargo that had virtually ruined their economy.

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a CIA offshoot, funded the anti-Sandinista newspaper (La Prensa) of the winner, Violeta Chamorro, who had married into the Chamorro clan.[15]

In 1996 elections, the Clinton administration supported conservative Arnoldo Alemán, a darling of the anti-Castro Cuban lobby and right-wing Nicaraguan exile community who attempted to undo the legacy of the Sandinista revolution by pushing for the privatization of state-run industries, and reduction of social services and tariffs while restoring property rights, courting foreign investors and solidifying good relations with the U.S.

Three out of four Nicaraguans during Alemán’s presidency lived in poverty and not one in two had steady work.

[Source: elpulso.hn]

Taking a long view, as Kovalik does in his book, one can see the continuity in U.S. foreign policy from the late 19th century to the present.

As much as one can expect further U.S. interference in Nicaragua, one can also expect continued resistance as Sandino’s legacy lives on.

Notes:

- ↩ Dan Kovalik, Nicaragua: A History of U.S. Intervention & Resistance (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2023), 195. Allegedly, Ortega suffered brutal torture during his years in captivity.

- ↩ Dan Kovalik, Nicaragua, 199.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 226.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 250.

- ↩ Ortega’s independence in foreign policy was reflected in his a) refusing to send Nicaraguan troops to be trained at the U.S. Army School of the Americas; b) providing a safe haven to Honduran President Manuel Zelaya after he was ousted in a U.S.-backed coup in 2009; and c) supporting Muammar Qaddafi—another Reagan nemesis—during the 2011 U.S.-NATO invasion of Libya.

- ↩ Noam Chomsky has described how Díaz did wonders for U.S. business and banking interests, which began to receive the revenues of the Nicaraguan national rail and steamship lines. A U.S.-run commission required Nicaragua to pay fraudulent “damage claims” that exceeded total U.S. investment in the country for alleged “damages from civil disorder.”

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 26.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 250. A historian described the U.S. aerial bombings as “a remorseless faceless enemy inflicting indiscriminate violence against homes, villages, livestock, and people who, regardless of age, gender, physical strength, social status [and who] lacked any defense except to salvage their belongings.” (p. 8).

- ↩ An indication of the heavy U.S. backing was that Nicaragua during the Somoza era was the only country which annually sent the entire graduating class of its military academy for a full year of training at the U.S. Army School of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia. Kovalik, Nicaragua, 74.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 60.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 3. For more on Linder and his death, see Joan Kruckewitt, The Death of Ben Linder: The Story of a North American in Sandinista Nicaragua (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1999).

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 92, 93.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 117.

- ↩ Kovalik, Nicaragua, 111, 126.

- ↩Democratic Congressman George Miller, a true liberal who opposed U.S. foreign policy in Central America in the 1980s, stated sarcastically on the floor of the House, mocking the Reagan and Bush administration policies: “We are [going] into this election process [1990] [spending] $1 billion. We funded the Contras, we have destroyed [Nicaragua’s] economy, we have taken Mrs. Chamorro, and…we pay for her newspaper to run,…we funded her entire operation, and now we are going to provide her the very best election that America can buy.” Congressional Record, October 4, 1989, p. H6642. Miller further stated in this speech that “These Contras would not fight unless we paid them. UNO would not stay in business unless we paid them. They have squirreled away the money in their bank accounts. And apparently now they will not register and go vote unless we pay them. Is this not a time that we make this a Nicaraguan election rather than an American election? Is it not time that we step back and let the Nicaraguan people decide this?…We should not be spending this money and sending it down the same rat hole with the same rats that took us for a billion dollars.”