The New York Times (5/30/23) directs attention toward a hypothetical future AI apocalypse, rather than towards present-day AI’s entrenchment of contemporary oppression.

It’s almost impossible to escape reports on artificial intelligence (AI) in today’s media. Whether you’re reading the news or watching a movie, you are likely to encounter some form of warning or buzz about AI.

The recent release of ChatGPT, in particular, led to an explosion of excitement and anxiety about AI. News outlets reported that many prominent AI technologists themselves were sounding the alarm about the dangers of their own field. Frankenstein’s proverbial monster had been unleashed, and the scientist was now afraid of his creation.

The speculative fears they expressed were centered on an existential crisis for humanity (New York Times, 5/30/23), based on the threat of AI technology evolving into a hazard akin to viral pandemics and nuclear weaponry. Yet at the same time, other coverage celebrated AI’s supposedly superior intelligence and touted it as a remarkable human accomplishment with amazing potential (CJR, 5/26/23).

Overall, these news outlets often miss the broader context and scope of the threats of AI, and as such, are also limited in presenting the types of solutions we ought to be exploring. As we collectively struggle to make sense of the AI hype and panic, I offer a pause: a moment to contextualize the current mainstream narratives of fear and fascination, and grapple with our long-term relationship with technology and our humanity.

Profit as innovation’s muse

So what type of fear is our current AI media frenzy actually highlighting? Some people’s dystopian fears for the future are in fact the dystopian histories and contemporary realities of many other people. Are we truly concerned about all of humanity, or simply paying more attention now that white-collar and elite livelihoods and lives are at stake?

We are currently in a time when a disproportionate percentage of wealth is hoarded by the super rich (Oxfam International, 1/16/23), most of whom benefit from and bolster the technology industry. Although the age-old saying is that “necessity is the mother of invention,” in a capitalist framework, profit—not human need—is innovation’s muse. As such, it should not be so surprising that human beings and humanity are at risk from these very same technological developments.

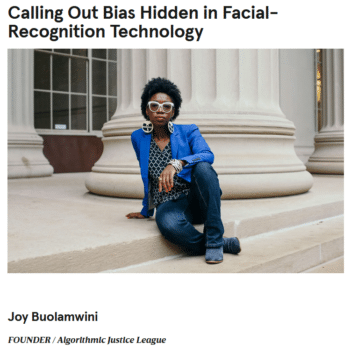

Wired (10/15/19): Joy Buolamwini “learned how facial recognition is used in law enforcement, where error-prone algorithms could have grave consequences.”

Activists and scholars, particularly women and people of color, have long been sounding the alarm about the harmful impacts of AI and automation. However, media largely overlooked their warnings about social injustice and technology—namely, the ways technology replicates dominant, oppressive structures in more efficient and broad-reaching ways.

Cathy O’Neil in 2016 highlighted the discriminatory ways AI is being used in the criminal justice system, school systems and other institutional practices, such that those with the least socio-political power are subjected to even more punitive treatments. For instance, police departments use algorithms to identify “hot spots” with high arrest rates in order to target them for more policing. But arrest rates are not the same as crime rates; they reflect long-standing racial biases in policing, which means such algorithms reinforce those racial biases under the guise of science.

Joy Buolamwini built on her own personal experience to uncover how deeply biased AI algorithms are, based on the data they’re fed and the narrow demographic of designers who create them. Her work demonstrated AI’s inability to recognize let alone distinguish between dark-skinned faces, and the harmful consequences of deploying this technology as a surveillance tool, especially for Black and Brown people, ranging from everyday inconveniences to wrongful arrests.

Buolamwini has worked to garner attention from media and policymakers in order to push for more transparency and caution with the use of AI. Yet recent reports on the existential crisis of AI do not mention her work, nor those of her peers, which highlight the very real and existing crises resulting from the use of AI in social systems.

Timnit Gebru, who was ousted from Google in a very public manner, led research that long predicted the risks of large language models such as those employed in tools like ChatGPT. These risks include environmental impacts of AI infrastructure, financial barriers to entry that limit who can shape these tools, embedded discrimination leading to disproportionate harms for minoritized social identities, reinforced extremist ideologies stemming from the indiscriminate grabbing of all Internet data as training information, and the inherent problems owing to the inability to distinguish between fact and machine fabrication. In spite of how many of these same risks are now being echoed by AI elites, Gebru’s work is scarcely cited.

Although stories of AI injustice might be new in the context of technology, they are not novel within the historical context of settler colonialism. As long as our society continues to privilege the white hetero-patriarchy, technology implemented within this framework will largely reinforce and exacerbate existing systemic injustices in ever more efficient and catastrophic ways.

Conversation (4/19/23): “News media closely reflect business and government interests in AI by praising its future capabilities and under-reporting the power dynamics behind these interests.”

If we truly want to explore pathways to resolve AI’s existential threat, perhaps we should begin by learning from the wisdom of those who already know the devastating impacts of AI technology—precisely the voices that are marginalized by elite media.

Improving the social context

Instead, those media turn mostly to AI industry leaders, computer scientists and government officials (Conversation, 4/19/23). Those experts offer a few administrative solutions to our AI crisis, including regulatory measures (New York Times, 5/30/23), government/leadership action (BBC, 5/30/23) and limits on the use of AI (NPR, 6/1/23). While these top-down approaches might stem the tide of AI, they do not address the underlying systemic issues that render technology yet another tool of destruction that disproportionately ravages communities who live on the margins of power in society.

We cannot afford to focus on mitigating future threats without also attending to the very real, present-day problems that cause so much human suffering. To effectively change the outcomes of our technology, we need to improve the social context in which these tools are deployed.

A key avenue technologists are exploring to resolve the AI crisis is “AI alignment.” For example, OpenAI reports that their alignment research “aims to make artificial general intelligence (AGI) aligned with human values and follow human intent.”

However, existing AI infrastructure is not value-neutral. On the contrary, automation mirrors capitalist values of speed, productivity and efficiency. So any meaningful AI alignment effort will also require the dismantling of this exploitative framework, in order to optimize for human well-being instead of returns on investments.

Collaboration over dominion

Greta Byrum & Ruha Benjamin (Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6/16/22): “Those who have been excluded, harmed, exposed, and oppressed by technology understand better than anyone how things could go wrong.”

What type of system might we imagine into being such that our technology serves our collective humanity? We could begin by heeding the wisdom of those who have lived through and/or deeply studied oppression encoded in our technological infrastructure.

Ruha Benjamin introduced the idea of the “New Jim Code,” to illustrate how our technological infrastructure reinforces existing inequities under the guises of “objectivity,” “innovation,” and “benevolence.” While the technology may be new, the stereotypes and discriminations continue to align with well-established white supremacist value systems. She encourages us to “demand a slower and more socially conscious innovation,” one that prioritizes “equity over efficiency, [and] social good over market imperatives.”

Audrey Watters (Hack Education, 11/28/19) pushes us to question dominant narratives about technology, and to not simply accept the tech hype and propaganda that equate progress with technology alone. She elucidates how these stories are rarely based solely on facts but also on speculative fantasies motivated by economic power, and reminds us that “we needn’t give up the future to the corporate elites” (Hack Education, 3/8/22).

Safiya Noble (UCLA Magazine, 2/22/21) unveils how the disproportionate influence of internet technology corporations cause harm through co-opting public goods for private profits. To counter these forces, she proposes “strengthening libraries, universities, schools, public media, public health and public information institutions.”

These scholars identify the slow and messy work we must collectively engage in to create the conditions for our technology to mirror collaboration over domination, connection over separation, and trust over suspicion. If we are to heed their wisdom, we need media that views AI as more than just the purview of technologists, and also engages the voices of activists, citizens and scholars. Media coverage should also contextualize these technologies, not as neutral but as mechanisms operating within a historical and social framework.

Now, more than ever before, we bear witness to the human misery resulting from extractive and exploitative economic and political global structures, which have long been veiled beneath a veneer of “technological progress.” We must feel compelled to not just gloss over these truths as though we can doom scroll our way out, but collectively struggle for the freedom futures we need—not governed by fear, but fueled by hope.