Thierry Deronne is a Belgian-born filmmaker who has long accompanied working-class and campesino struggles in Latin America. In the mid-1990s in Venezuela, he fostered popular media and educational projects, and he later played a key role in the community television movement during the Bolivarian Revolution. Deronne is currently a professor at the National University of the Arts [Unearte]. His most recent documentary is Nostálgicas del futuro, a film about working-class feminism in Venezuela.

In Part One of this two-part interview, Deronne talked about the philosophy driving the community media movement earlier this century and the different experiments in communication that went along with it. In Part Two, the filmmaker discusses the future of popular communication, and specifically his current project: the Escuela Popular de Cine y Teatro Hugo Chávez [Hugo Chávez Popular Cinema and Theater School].

In Antímano, Caracas, a group of women are self-building their homes. The Popular Cinema and Theater School works with them to promote grassroots communication. (@cine_escuela)

Cira Pascual Marquina: In the early years of the Bolivarian Process, community media thrived. However, the community media movement has unfortunately declined over the years. Why do you think this happened?

Thierry Deronne: The main reason the movement wound down is the formidable weight of capitalist television. Community TV stations emerged as islands within the vast ocean of capitalist communication, and some people failed to recognize the potential of participatory television as a tool for empowering the people.

A solution would have involved a new communication policy that promoted the proliferation of community outlets on a large scale to foster the emergence of a truly transformative model. Naturally, this expansion would have needed to be complemented by widespread, continuous training and education in emergent practices.

Internal issues also contributed to the decline, notably the lack of cohesion within the movement, resulting in territorial disputes, sectarianism, de facto personal or familial appropriation of existing community media, and more.

There was another bottleneck for grassroots media: technology was prohibitively expensive back then, and the organizations struggled to generate sufficient income for the maintenance or replacement of outdated and damaged equipment.

Today, smartphones offer more affordable and lightweight technology that could facilitate popular audiovisual production and education. However, Silicon Valley subsumes these tools under a logic of capitalist consumption, shaping formats into short, flashy, and narcissistic content. This shift has political repercussions, as evidenced by the rise of figures like Trump, Bolsonaro, and Milei.

There are two urgent tasks today. First, the revitalization of popular communication with state support to establish a new model. This will require funding, particularly for education and training. Second, it’s imperative to create a new kind of social media. We should bring digital media experts into contact with social movements to create a new social media that is not bound by market constraints but rather shaped by the time required to narrate the stories of people organizing in their communities.

The Popular Cinema and Theater School accompanies an audiovisual nuclei at El Maizal Commune. (@cine_escuela)

CPM: For the past few years, you’ve been working on the Hugo Chávez Popular Cinema and Theater School, a contemporary iteration of your communication school dating back to the 90s. Could you elaborate on the nature of this new project?

TD: Documenting a revolution is vital for many reasons. Key among them are preserving historical memory and transmitting the experience. Additionally, agitation and propaganda, as well as fostering self-critique, are important in any revolutionary process. Our school tries to do all that. It is also a space to study reality: documentary filmmaking should give us the time to understand processes dialectically.

Given the context in which our revolution was born, commercial television became the reference point, with soap-opera production serving as a quasi-school for many in the media. Consequently, the development of documentary work has been limited within the Bolivarian Process. As far as the production of fiction is concerned, the narratives, while refined, often adhere to the prescriptive logic of the soap operas, creating an impression that we are in a country where a revolution never happened.

To address this, the Popular Cinema and Theater School began to organize production nuclei at a local level. El Maizal Commune has its own Popular Communication School now, but there are also workgroups in the Che Guevara Commune and elsewhere. The overarching goal is the same as always: producing audiovisual content where the community is organizing.

At Vive TV, time constraints hindered the creation of new productive bases that could ensure that programming was fully produced by the people in organized communities. Our current objective is to promote a space that brings together diverse perspectives and experiences. In essence, we are revisiting Chávez and his “3 Rs.” Revolutions demand a continuous reset process—constantly reviewing, rectifying, and relaunching. Without this dynamic approach to communication, there’s a risk of creating an isolated ivory tower, stunting the growth of the revolution.

Left, a theater workshop with Douglas Estevam. Right, an Epic Theater scene. Both in the Jorge Rodríguez Padre self-construction project in Antímano, Caracas. (@cine_escuela)

CPM: Does the Popular Cinema and Theater School also organize theater workshops?

TD: Certainly, our school promotes and facilitates theater workshops and engages in theater-making, drawing from both the Brazilian tradition of the “Theater of the Oppressed” and Bertolt Brecht’s “Epic Theater.” To do this, we collaborate with two compañeros from Brazil: Douglas Estevam from the MST’s Culture Collective and Julian Boal from the Theater of the Oppressed tradition.

In 2023, Douglas collaborated with women in Antímano, Caracas, who are organized around the project of self-constructed housing. They used their own lives as material to craft epic images of their struggle. Simultaneously, Julian initiated a collaborative project with the group that focused on gender-based violence.

This theater initiative aims to break away from the dominant soap opera-influenced plays in Venezuela. Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed and Bertolt Brecht’s Epic Theater are perfect channels for building a participatory democracy, which is a core principle of the Bolivarian Revolution. These theater traditions enable us to leave behind that anachronistic kind of theater where a few have the right to be on stage while most only have the right to be passive spectators.

Our commitment to this approach is anchored in the Marxist notion that a technique implies an ideology. Looking ahead to 2024, our plan is to implement a cycle that involves training, practice, reflection, and follow-up. We will also embark on a collaboration with a troupe of clowns involved in the building-occupation movement. We will foster small-scale exercises in Theater of the Oppressed, with a view toward moving on to more elaborate forms of Epic Theater. To enrich our work, we also enrolled the expertise of an extraordinary Brazilian director and dramaturge: Sérgio De Carvalho and his Compañía do Latão.

CPM: You produce and direct documentaries. Some are collective endeavors and others are more “traditional” in the sense that you are the director. How does that work?

TD: Our production approach is diverse, but we always place people at the forefront. Some documentaries involve collaborative authorship with social organizations. Take “Marcha,” a production centered on the Admirable Campesino March [2018]. Much of the material for that work originated from the campesinos themselves, but we also documented parts of the march. In the end, we edited the material, but the campesinos guided us in the process.

Then there are films such as “Nostálgicas del futuro” [2023], a documentary about popular feminism, that I directed. I have the privilege of visiting many places where people are organizing. This allowed me to weave together various struggles into a cohesive film. Now I am working on a documentary exploring communal economies, but it will look beyond strictly communal initiatives to encompass other emerging economic models.

Additionally, there are documentaries made directly by an organization. For instance, Lana Vielma and other folks from El Maizal are making a documentary about the assemblies they carry out in remote areas of the commune.

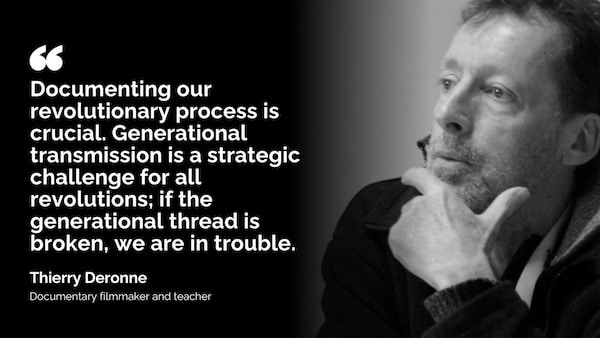

One of the urgent tasks now is creating the documentary filmmaking school. As I mentioned before, documenting our revolutionary process is crucial. Generational transmission is a strategic challenge for all revolutions; if the generational thread is broken, we are in trouble, because the empire knows how to take advantage of such ruptures.