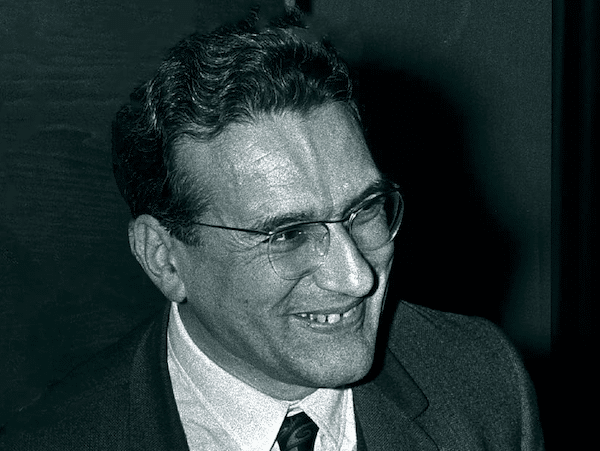

Some of Ernest Mandel’s finest work on Marxist theory and revolutionary politics appeared in the form of short articles. Hope and Marxism collects eleven of Mandel’s most significant articles and provides an excellent introduction to his thought.

Ernest Mandel – Hope and Marxism: Historical and Theoretical Essays

The first article, ‘Althusser Corrects Marx’ (1969), represents Mandel’s contribution to the Marxist humanism debate. Althusser argued that Marx underwent an epistemological break in the 1860s, in which he abandoned the humanism of the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and broke from Hegelian idealism. In ‘The Causes of Alienation’ (1970), Mandel shows that there was no epistemological break between the young and old Marx, but ‘an important evolution, not identical repetition, in Marx’s thought from decade to decade’ (40). A product of Marx’s humanism was the concept of alienation, which shows that working people under capitalism are alienated from the product of their labour, from each other and from themselves. Four features of alienation appear in a more mature form in Capital, which include the separation of the worker from the means of production, the generalisation of the sale of labour-power, the product belonging to the employer rather than the worker, and the loss of labour’s creative content. Mandel’s exposition is helpful and relevant, as many working people today are alienated through working uncreative, meaningless jobs that provide little satisfaction. For many, work is ‘something which is not productive or creative for human beings but something which is harmful and destructive’ (45).

Mandel argues that the solution to alienation is not more leisure time, for consumption is often just as alienated as production. In a way similar to Sweezy and Baran in Monopoly Capital, Mandel notes that through marketing and planned obsolescence, capitalists constantly render us dissatisfied in order to generate the desire for new products. Our relation to other people are also alienated and mediated by the commodity-form, for Mandel notes a tendency to treat people through socially defined functions (i.e. customer, student, client, patient, etc.). Alienation can only be overcome by socialism, which results in a planned economy that has abolished commodity production and private ownership of the means of production. Mandel denies that former socialist countries like the USSR, East Germany and Cuba managed to fully abolish alienation, insofar as they were transitional social formations that had eliminated capitalist property relations but had not ‘abolished the division of society into classes, they still have different social classes and different social layers’ (52). While life was materially better in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, the bureaucratic deformation of political and social life resulted in similar patterns of alienation as witnessed in the capitalist world.

In ‘Rosa Luxemburg and German Social Democracy’ (1977) and ‘A Critique of Eurocommunism’ (1979), Mandel examines reformist currents in the communist movement. He engages with a text from Engels (1870), who argued that the workers movement in Germany should utilise elections in order to agitate for socialism and win millions to revolutionary Marxism. Whereas Engels viewed parliamentary election as a tactic of a larger revolutionary strategy, his followers in the SPD, such as Bernstein, used it to argue for a non-revolutionary parliamentary road to socialism. Mandel emphasises that Rosa Luxemburg was one of the few figures who took a clear stance against electoralism and warned that it would fail ‘if the masses were not trained well in advance in the politics of extra-parliamentary action as well as routine electoralism and purely economic strikes’ (58). Taking inspiration from the 1905 Russian Revolution, Luxemburg advocated for a mass workers strike and predicted that the SPD party bureaucrats would oppose such actions in order to maintain their parliamentary privileges. Mandel notes that because the Second International was under the command of party bureaucrats, the masses became passive. This passivity enabled the leaders of the SPD and other Second International parties to call for the ‘defence of the fatherland’ during the First World War.

Luxemburg agitated for a party with a clear programme, which would intervene in workers’ struggle to ‘ensure that on the day of the revolution the party would be the driving force of the proletariat and not its bureaucratic hangman’ (71). While the article is helpful in allowing us to appreciate Luxemburg’s contributions to Marxist politics, it is somewhat reductive and does not bring out the rich debates that took place in the Second International of which Luxemburg was a major participant. These debates, recently compiled by Mike Taber in Reform, Revolution, and Opportunism and Under the Socialist Banner, show that while the SPD did later develop in an extremely opportunist direction, the debates around parliamentarism and war were far more complex than Mandel’s account. In Taber’s work we see a wide cast of characters who took a range of positions on party-building, strategy and tactics, elections and socialism.

Mandel further explores reformism in ‘A Critique of Eurocommunism’ (1979), which explores the eurocommunist current in the French (PCF), Italian (PCI), Spanish (PCE) and Japanese (JCP) communist parties. Eurocommunism was a current in the 1970s, in which communist parties engaged in coalitions with other socialist parties and social movements in order to seize state power through parliament. In the PCF and PCI, this resulted in major revisions to established party doctrine, such as removing ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’ from the programme and sharp criticisms of the Soviet bureaucracy in order to appeal to more voters. They adopted the anti-monopoly strategy, which sought to unite trade unions, small business owners, oppressed peoples movements and even sections of the bourgeoisie against ‘monopoly capitalism’. If elected, the Communist Party would expropriate monopoly property, strengthen union power and delink from the global capitalist system.

Mandel views eurocommunism as a continuation of the Popular Front strategy pursued by the Third International in the 1930s, in which communist parties around the world formed alliances with the national bourgeoisie in order to protect democracy against fascism. As the PCF, PCI, PCE and JCP had all become hugely powerful organisations by the 1970s that could garner millions of votes, Mandel notes that a bureaucracy emerged within bourgeois parliaments with special privileges. He claims that the reason why they adopted a critical attitude towards the USSR was not in order to honestly break from Stalinism, but because the parliamentary CP bureaucracies had shifted their allegiance towards the bourgeoisie. Just like in the period of the Popular Front, the eurocommunist parties abandoned revolutionary Leninism in order to collaborate with the bourgeoisie and gain special privileges. While he views the rehabilitation of Trotsky and Bukharin in the eurocommunist period as positive, Mandel analyses eurocommunism from within the Trotskyist paradigm and compares it to the opportunist turn of the Second International.

In a further critique of eurocommunist politics, ‘On the Class Nature of the Capitalist State’ (1980), Mandel argues that socialist transformation is impossible through elections. He distinguishes between state power and state management. Following Lenin, Mandel views the capitalist state as an instrument of repression that is necessary for the reproduction of capitalist social relations. While the bourgeoisie always holds state power in a capitalist state, other classes can manage the state in certain social formations. For example, in the period of fascism in Germany and Italy, sections of the petty-bourgeoisie managed the capitalist state in order to crush the workers movement through organised terror. Mandel concludes that if the eurocommunists were to get elected into power, they would manage the capitalist state for the bourgeoisie until they were no longer useful and then be overthrown, as happened in Chile in 1973 with Pinochet’s coup.

Despite being non-revolutionary and a major cause of the liquidation of many communist parties around the world, eurocommunism had a leftist current within it led by Nikos Poulantzas. Poulantzas was critical of the eurocommunist strategy but could appreciate some of the questions it raised and the ways it engaged with non-communist movements like feminism. For example, the eurocommunist parties drew significant attention to the nature of the capitalist state in a way that Lenin, Trotsky and other Third International figures did not. While Mandel briefly engages with Poulantzas in his longer work From Stalinism to Eurocommunism, his approach is to dismiss him by claiming that Poulantzas veered too much from Marxist orthodoxy. Such an attitude prevents Mandel from integrating new theory into Marxism, which he treats as a fully worked-out doctrine.

In ‘We Must Dream’ (1978), Mandel engages with the work of Ernest Bloch, who is known for his introduction of utopianism and revolutionary vision into communist thought. Mandel argues that Bloch’s category of hope is a fundamental aspect of all revolutionary movements that gives ‘it an energy and driving power, which cannot arise exclusively from the defence of daily material interests’ (115). Those who have dedicated their life to the fight for a communist, classless society are often inspired by a vision which the most fundamental defeats cannot break. This communist faith anticipates something without any current existence, but is materially possible and therefore inspires revolutionary praxis. Revolutionaries like Fidel Castro, Amilcar Cabral and Maurice Bishop were able to gain the trust of millions of people not solely on the basis of their programme, but because they provided an emancipatory vision and showed the way to achieve it.

Hope and Marxism illustrates the incredible depth of Mandel’s thinking over a period of 25 years. It is a fine collection of essays that gives helpful overview to Mandel’s thought during the seventies and eighties. It is a great book for those who are new to Marxism and eager to see certain threads on how Marxists have approached electoral politics, the capitalist state and socialist revolution.

References:

- 2023 Reform, Revolution, and Opportunism and Under the Socialist Banner (Chicago: Haymarket Books).