A government report on the national “housing price spiral” expresses concern over “the level of housing starts in Canda in relation to projected demand.” It observes that these supply-and-demand factors are contributing to the “inability of low-and middle-income Canadians to purchase their own homes.” It further comments on the problem of high interest rates, inflating utility costs, and “increases in the capital costs of construction.”

This report could be describing the housing market in 2024. Or any other year in the last ten for that matter. But this report, an evaluation of the Federal Housing Action Program, or FHAP, was produced nearly a half-century ago, and details Ottawa’s response to the housing crisis of the 1970s.

At the beginning of that decade housing costs were out of control, and homes “were increasingly priced beyond the means of even moderate-income Canadians.” In response, the federal government launched the FHAP, which saw the state build social housing, subsidize rents, and provide discounted mortgages to homebuyers.

The program was a roaring success. By the end of the decade housing prices had gone down in real terms. Workers could buy a home. Those who preferred to rent had a wide variety of quality social housing solutions available at any income. Homelessness became a marginal phenomenon.

Remarkably, the same housing crisis afflicting Justin Trudeau’s tenure as prime minister was more or less resolved by his father’s government after just a few short years.

Understanding those solutions can help bring us back to a just, stable housing market.

The FHAP encompassed a series of programs which deployed government resources to address the housing crisis through non-market solutions. The most important of these was the construction of social housing.

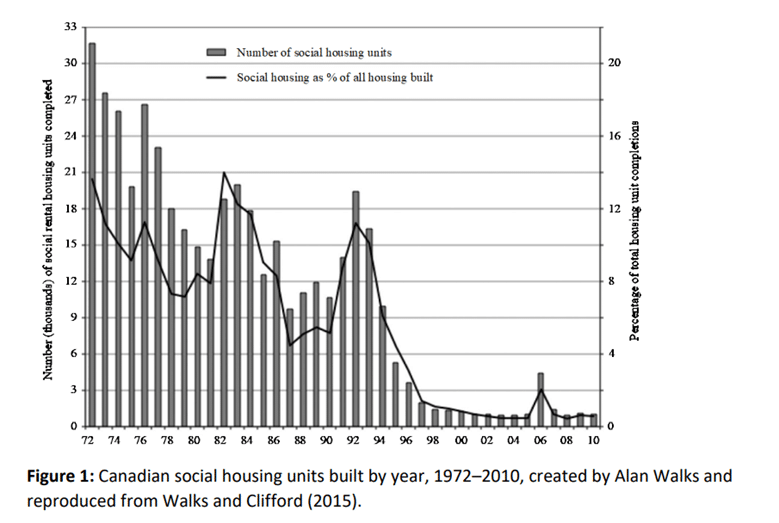

From 1972 onward, between 10-20 percent of all housing built in Canada was public, non-profit, or co-operative owned. These units came with various affordability covenants that anchored prices. Suddenly, private landlords had to compete with a robust public sector that prioritized affordability instead of wealth extraction, lowering costs for everyone.

But there was more to the FHAP than the construction of non-market housing. Renters could have their monthly payments subsidized through the Assisted Rental Program (ARP). Low-income folks who wanted to own a home could secure below-market rate mortgages directly from the federal government, or have their private mortgages subsidized through the Assisted Home Ownership Program (AHOP).

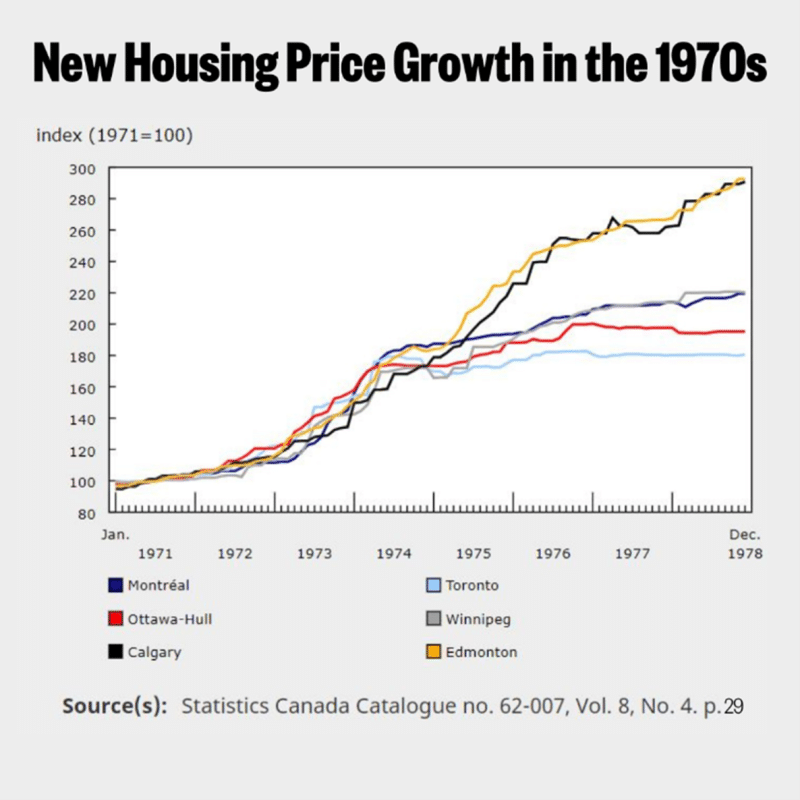

These initiatives took effect quickly. The price spiral was interrupted and, year after year, housing prices stabilized. Against a backdrop of high wage and price inflation, this levelling off of costs meant that housing became significantly more affordable.

In Toronto, where participation in FHAP programs was high, real housing costs fell by 30 percent between 1974 and 1978. In an incredible natural experiment, provinces with high participation rates felt the benefits of reduced housing costs while those with low rates of participation (such as Alberta, which, under premier Peter Lougheed, went its own way on housing policy) saw home prices rise with inflation.

The results were spectacular: FHAP programs restored housing affordability in less than a decade.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, not everyone was thrilled with this outcome. The business class and their factotums in the scribbling professions clutched their pearls. The Fraser Institute screeched that “housing policy effectively became an instrument to redistribute income in favour of lower income households.”

Sadly, good policy doesn’t last long in Canada. The 1980s came and with it an election and a bust in the real estate market. It was deemed necessary to ‘commercialize’ the nation’s housing policies. Ottawa stopped subsidizing rents and mortgages and slowed down investments in social housing. Policy refocused on insuring private debt and authorizing the creation of mortgage-backed securities.

As Parliament reoriented towards the private sector, prices rose. By the late 1980’s increases in housing costs led to a homelessness epidemic, which is still with us today. This is another, grimmer, natural experiment confirming the vast scientific literature showing that housing is indeed the only solution to homelessness.

Despite the obvious inability of the private sector to manage the nation’s housing needs, the federal government doubled down. In 1992 it ended the co-operative housing program, and by the middle of the decade it stopped funding the construction of new affordable housing.

By the end of 1990s, the feds had washed their hands of housing entirely. They transferred the administration of any remaining housing programs to the provinces and territories, which were then largely downloaded further to municipalities. Existing social housing stock languished under these lower orders of government; chronically underfunded and left to decay, they were (and are) frequently sold off by capricious, short-sighted premiers and city councils.

At the turn of the millennium Canada’s national housing programs—which had generated more than half of the country’s affordable homes—were no more.

By the time Justin Trudeau was elected in 2015, housing had come full circle. Just like in the 1970s prices were spiraling, Canadians were being locked out of homeownership, and rents were out of control. And like his father, Justin decided to do something. He launched the National Housing Strategy (NHS) which dedicated tens of billions of dollars to resolving the crisis.

But the NHS is not the FHAP. The NHS sees housing exclusively through the lens of supply-and-demand. The theory is that if enough homes can be built prices will go down. To build units quickly the NHS funnels money primarily to developers who, in turns out, have been selling their builds to speculators of all sizes. These market-oriented solutions have backfired. Since the launch of the NHS housing prices have continued to rise.

This outcome was entirely predictable. Skyrocketing prices on a backdrop of increasing supply was the defining quality of the housing market in the decade leading up to the NHS when, year after year, Canada built an average of 30,000 more homes than was needed to accommodate population growth and prices still outpaced inflation.

The evidence is clear: Canada’s housing crisis is not a simple supply and demand problem. It is a problem of who owns our homes and why. By focusing almost exclusively on expanding supply through the private sector the NHS has given our housing system over to predaceous investors while deeply indebting everyday Canadians.

In 1978 the housing market had been made into an engine of wealth redistribution; massive investments in social housing reduced income inequality and moved us towards a more egalitarian society. Today, housing has once again become a machine to redistribute the nation’s treasure, only this time the money is being directed to the top.

To solve this crisis we need to turn away from neoliberal doctrines about the primacy of the private enterprise and look towards solutions that actually work. Our own history, as well as the experiences of our contemporaries abroad, teach us that the only way to restore housing affordability is to create non-market housing alternatives that anchor prices and push the investor class out of the housing system.

We need social housing capable of charging rent-geared-to-income, a federal housing benefit, and universal rent control. We need a public retail banking system able to provide mortgages at terms favorable to low-income buyers and we need the interest collected on those mortgages to be used to build and maintain even more social housing.

The places we live can no longer be allowed to exist as investment vehicles for speculators, they must become what they should have always been—our homes.

James Hardwick is a writer and community advocate. He has over ten years experience serving adults experiencing poverty and houselessness with various NGOs across the country.