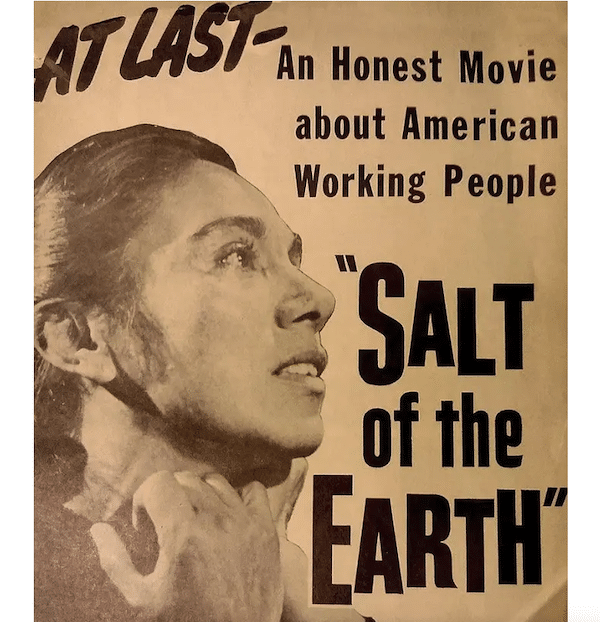

In many ways, 1954’s Salt of the Earth is a singular, cinematic phenomenon, one of the most unique American movies ever made. At a time when star-driven Hollywood was cranking out widescreen biblical epics, technicolor musicals, sci-fi and horror B pictures for drive-ins, Westerns, comedies, as well as films starring highly trained “Method” actors, Salt featured a largely nonprofessional cast in a story about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. These non-actors played versions of themselves—miners who had struggled in a recent, real-life strike.

In an era when flicks were typically made at Tinseltown studios, soundstages and backlots and set in glamorous big cities or exotic fantasylands such as Brigadoon and South Pacific, Salt was set and shot in black and white on location in nitty-gritty New Mexico. While Tinseltown’s stars and dramatis personae were almost exclusively white, Salt’s leads and most of its characters were of Mexican heritage.

In an age when Gentlemen Prefer-red Blondes like Marilyn Monroe, Pillow Talk-ing Doris Day and conventional Ozzie and Harriet housewives, Salt’s brown women broke gender roles, walked the picket line, clashed with police and its female lead, Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas who portrayed Esperanza Quintero, was born in Durango.

Rosaura Revueltas in Salt of the Earth. [Source: dweemeister.tumblr.com]

Huelga: The Empire Zinc Miners’ Strike

1950s Hollywood movies may have focused on fantasy and make believe, places far away and long ago, but as mentioned above, Salt of the Earth is a fact-based, of-the-moment dramatization of a true-life strike. According to Monthly Review:

Negotiations with the union broke down when the company walked out after having refused to bargain with Local 890. The miners were asking for a raise of fifteen cents per hour and six paid holidays. EZ [Empire Zinc] offered a five-cent raise but only if the workers agreed to a forty-eight-hour work week in place of their current forty hours. The members voted overwhelmingly to strike.

On October 17, 1950, Local 890 of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW) walked off the job at Hanover, New Mexico, launching a long, drawn-out strike against the Empire Zinc Company (or EZ), a New Jersey Zinc subsidiary. The miners’ demands included an end to discriminatory practices, with pay parity for Mexican and Mexican-Americans and Caucasian employees. For eight months the men picketed Empire Zinc until June 1951, when a dozen picketers, including Clint Jencks, were arrested and the Grant County District Court issued an injunction threatening to jail miners who picketed.

A scene from Salt: On the right is union leader Juan Chacón as union leader Ramon Quintero, with Clint Jencks as organizer Frank Barnes. [Source: portside.com]

The hard-fought huelga lasted about 15 months. According to the 2013 book Palomino: Clinton Jencks and Mexican American Unionism in the American Southwest by James J. Lorence, professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin-Marathon County:

On January 21, 1952, after three days of hard bargaining… a new contract included provisions for a substantial wage increase, payments as alternative to collar-to-collar pay, added vacation and pension benefits, insurance provisions, rehiring of striking workers without discrimination, and an important contract renewal agreement that … align(ed) Local 890 with other area locals (i.e. whites)…. Hot running water and other housing upgrades also appeared to relate to the settlement. In the long run, workers saw the end of the hated ‘Mexican wage.’

The women of the Empire Zinc strike on the picket line. [Source: thenation.com]

Striking Lightning: A Movie is Born

It’s important to note that the IUMMSW, which can trace its roots at least as far back as 1893 when it was known as the Western Federation of Miners, had a history of militancy. This included ties to Communist Party organizers, such as Clint Jencks and his wife Virginia—who play versions of themselves in Salt of the Earth—are believed to have been at points in their lives. By 1950, during the Red Scare, the CIO expelled 11 unions from the labor federation, including IUMMSW.

According to Deborah Silverton Rosenfelt’s commentary in the 1978 book Salt of the Earth, the movie came about when circa 1951 Paul Jarrico, his wife Sylvia and son Bill vacationed at a lefty-friendly guest ranch in San Cristobal, New Mexico, founded by a union representative and folksinger, Jenny Wells Vincent. There the Jarricos socialized with the Jencks, who told the Jarricos about the Empire Zinc strike taking place 350 miles south. En route back to Los Angeles, the Jarricos stopped at the IUMMSW strike site at Grant County, where Sylvia and Billy joined the women to walk the picket line.

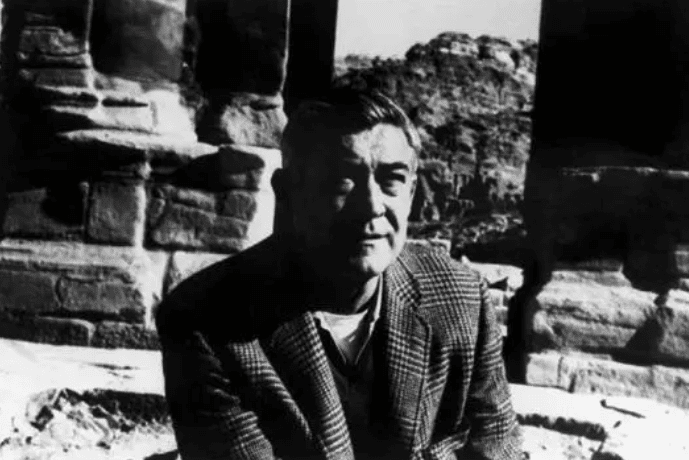

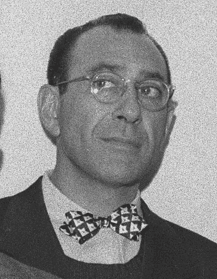

At that time, undeterred by the Blacklist, Jarrico, Herbert Biberman and his Hollywood Ten comrade, producer Adrian Scott, were determined to continue making movies outside of the Tinseltown studio system. To this end in 1951, along with a theater operator, they formed Independent Productions Corporation, but none of the stories they’d been considering had lit that proverbial lightbulb above their heads until the miners’ strike captured their attention. The ethnic, gender and class struggle aspects of the EZ strike struck lightning, appealing to the blacklisted progressives. They asked another banished talent, Michael Wilson, to write the screenplay and the Oscar-winner was dispatched to New Mexico to research the then-still unfolding, real-life strike.

Michael Wilson [Source: peoplesworld.org]

Hollywood’s Outcast Artists

Screenwriter Michael Wilson co-won his Academy Award for 1951’s A Place in the Sun and then for 1957’s The Bridge on the River Kwai—although he and co-writer Carl Foreman received no screen credit because they were blacklisted. Similarly, Wilson was later co-nominated for 1962’s Lawrence of Arabia, although his contribution to the screenplay wasn’t acknowledged (posthumously) by the Motion Picture Academy until 1995.

Herbert Biberman [Source: wikidata.org]

The Hollywood Ten was charged with contempt of Congress, found guilty, paid a fine and served prison time for refusing to answer questions such as: “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” and for refusing to inform on others suspected of being leftists to HUAC.

In The Film Encyclopedia, Ephraim Katz sums up Biberman’s oeuvre as “a modest career as director, screenwriter, and sometimes co-producer of low-budget Hollywood films.” He married Gale Sondergaard, who won the first Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for 1936’s Anthony Adverse and became the first celebrity to use her Oscar acceptance speech, broadcast nationwide on live radio, to advocate for a political cause. (According to 2000’s One of the Hollywood Ten, the actress urged support for the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. However, I have previously reported that she spoke out for Loyalists fighting Franco’s fascists during the Spanish Civil War.) Sondergaard was nominated again in the same Oscar category for 1946’s Anna and the King of Siam.

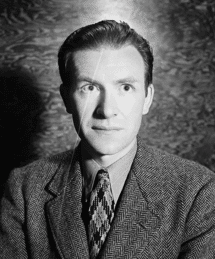

Before he was sidelined by HUAC, Paul Jarrico was a screenwriter Oscar-nominated for 1941’s Tom, Dick and Harry and probably most known (prior to Salt) for co-writing 1944’s Song of Russia, which extolled the heroism of America’s WWII ally. In her October 20, 1947 “friendly” HUAC testimony, laissez faire fanatic Ayn Rand singled out Song of Russia as an example of pro-Soviet propaganda, and especially excoriated the depiction of Russians in the MGM movie starring Robert Taylor, snarkily testifying: “I have never seen so much smiling in my life.” The only producer credit Jarrico has is for Salt.

Paul Jarrico [Source: youmustrememberthispodcast.com]

Will Geer [Source: commons.wikimedia.org]

The blacklisted artists and IUMMSW were simpatico. Jarrico is quoted as saying in Deborah Silverton Rosenfelt’s commentary in the 1978 book Salt of the Earth that IUMMSW “was constantly under attack for being a left-wing union. It was kicked out of the CIO for being a left-wing union. We were kicked out of Hollywood for the same reason. So if there was some similarity in thinking, it was no accident.”

Making Salt

Salt is largely a docudrama that was backed by the IUMMSW, which has a “presented by” screen credit. Wilson noted that, as a general rule, he “detested… writ[ing] by committee,” but the creative process of rendering Salt’s script was unusually collective, especially by Hollywood standards. While typical screenwriters may hate those dreaded “notes” from the “suits,” Wilson submitted his treatment for review and consideration by the mining community, which then gave the author feedback about stereotypes and various plot points, which the Caucasian scribe heeded.

This give-and-take between the artist who co-won an Oscar for co-writing A Place in the Sun, starring Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift and Shelley Winters, which scored six Academy Awards and was nominated for Best Picture, and about 400 miners enhanced the screenplay’s authenticity. “It made me better qualified to write the stories of their lives,” Wilson said.

The non-professional cast of miners, who in many cases were playing versions of themselves, also learned from the pros. In the 2000 feature film One of the Hollywood Ten about the making of Salt, Jeff Goldblum depicts Biberman, who patiently directs his dramatis personae. According to Arthur Revueltas, as the most professionally trained thespians at the New Mexico location, his Aunt Rosaura and Tinseltown actor Will Geer also helped coach and train the amateur actors—such as the male lead, real-life union local president Juan Chacón, who portrayed Esperanza’s husband, the movie’s union leader Ramon Quintero—in how to perform for the screen.

The uncanny result is arguably the best example of American Neo-Realist cinema during the heyday of the Italian Neo-Realism of De Sica, Rossellini, Visconti, Fellini, et al. The film’s style and content also harken back to the revolutionary period of Soviet silent cinema during the 1920s.

March 14, 1954 New York City premiere of Salt of the Earth. [Source: peoplesworld.org]

The Un-Making of Salt

Throughout the land of the free, reactionary forces from Hollywood to Washington to Silver City, NM, tried to prevent Salt of the Earth from being made. Then, after it was shot, sought to block the movie from completing post-production at film labs and editing facilities, from recording Sol Kaplan’s rousing score and from being distributed in theaters.

According to Paul Jarrico, as quoted in the 1978 Rosenfelt book, the harassment and disruptions, sometimes violent, took many forms: On February 25, 1953, immigration authorities arrested Rosaura Revueltas, and before shooting had been wrapped, the production’s lead actress was deported back to Mexico. On March 3, 1953, up to five bullets were fired into Clint Jencks’ car at Bayard at 1:30 a.m. During day, mob stops shooting of street scenes outside Union hall, knock over camera, punch members of crew and cast.’”

The same book states:

The final days of shooting took place under near-siege conditions, with the state highway patrol guarding the roads… on March 7, the home of Floyd Bostick, the film’s Jenkins, and the Mine-Mill union hall… were burned to the ground.

Various factors whipped up the mob violence. Jarrico notes the viciously anti-communist Hollywood Reporter’s first attack on Salt was the lead item in a gossip column on February 9, 1953: “H’wood Reds are shooting a feature-length anti-American racial issue propaganda movie at Silver City, NM.” The piece went on to say that SAG’s president “immediately alerted FBI, State Department, HUAC, and CIA.” Various rightwing pressure groups such as the American Legion also got into the act attacking Salt.

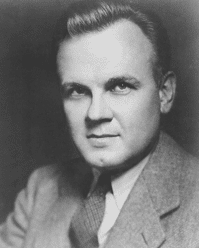

Congressman Donald Jackson [Source: govtrack.us]

On February 24, 1953 California Congressman Donald Jackson denounced Salt on the floor of the House, proclaiming: “I shall do everything in my power to prevent the showing of this Communist-made film in the theaters…” Howard Hughes, then a prominent producer and fierce foe of Salt, wrote to Jackson on March 18, 1953 calling on the motion picture industry to refuse supplies, equipment and technical support to the Salt filmmakers. (The film was developed and printed at labs under a false name, Vaya Con Dios, according to Biberman in his 1965 book Salt of the Earth, The Story of a Film. Clandestine cutting rooms were set-up in order to edit the movie, and the crew had to travel South of the border to shoot final close ups of the deported Rosaura in Mexico.)

To squelch distribution of Salt anti-communist zealot Roy Brewer ordered IATSE projectionists not to screen the movie and exhibitors were pressured not to run the film in their theaters and newspapers refused to publish ads. In March 1954 Salt finally theatrically opened in two New York theaters, but by September 1954, only a not-so-grand total of 13 theaters exhibited the controversial movie across the entire land of the not-so-free. The film co-made by blacklistees was, well, blacklisted…

Some of the cast members went on to literally suffer for their art. In addition to being thrown out of the USA, Rosaura Revueltas—who, according to her nephew Arthur Revueltas, moved in Mexico’s circles that included Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Leon Trotsky—was blacklisted in her home country. The Mexican actress, who had been awarded a Silver Ariel in 1953 and nominated for another one in 1951 by the Mexican Academy of Cinematographic Arts and Sciences, was forbidden from acting again on the Mexican big screen for 22 years, so according to Arthur, she toured Mexico with a vaudeville troupe and to act at Bertolt Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble theater in East Berlin.

Years later, asked in an interview if she was sorry she’d starred in Salt, Rosaura rather courageously replied:

I knew that with that film I would lose my career. So I made it with the full awareness of doing something for the Mexican people in the United States and to denounce what is still current. If the circumstances were to arise again, I would do the same.

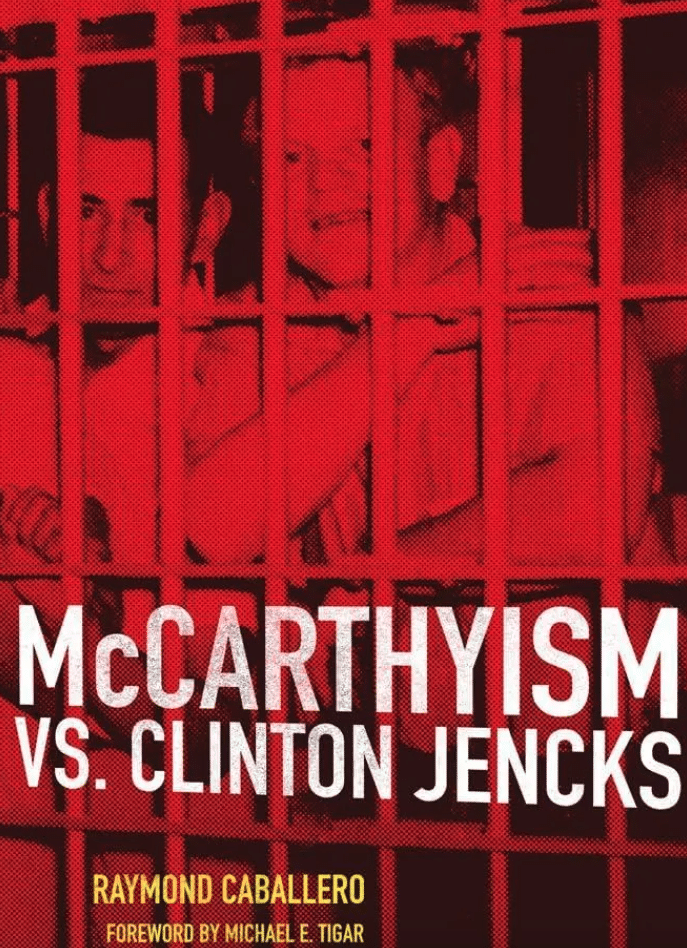

Raymond Caballero writes in his 2019 book McCarthyism vs. Clinton Jencks, that the true-life union organizer who portrayed Salt’s Frank Barnes (opposite his actual wife Virginia as Ruth Barnes), was considered to be “the outside Anglo agitator.” The longtime activist probably paid a steeper price for his involvement in Salt than almost anybody else.

Less than two months after principal photography for Salt ended, FBI agents arrested Jencks on April 30, 1953, and “brought him before a judge in EZ-dominated Silver City, charging him with two counts of filing a false affidavit saying he was not a member of the Communist Party. He had left the party when he signed the affidavit, an inconvenient fact the government chose to ignore in its prosecution (and persecution) of Clint and Virginia,” according to Monthly Review.

To make a long story short, Jencks was found guilty and “sentenced to two five-year terms to be served concurrently” (see: https://monthlyreview.org/2020/04/01/the-legacy-of-clinton-jencks/). Jencks’ Red Scare case wound through the courts for years until the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled in Clint’s favor in 1957.

Independent Productions Corporation wasn’t so lucky when it brought a lawsuit against a number of Hollywood entities, alleging a conspiracy to suppress Salt, which is detailed in Biberman’s book. Ironically, their leftist plaintiffs contended that the motion picture industry “co-conspirators” indulged in restraint of trade practices that deprived them of access to the free market. The expensive lawsuit laboriously wound its way through the courts for years until, predictably, on November 12, 1964, the jury found the defendants not guilty.

In addition to losing the IPC case, Herbert Biberman’s family may have actually suffered the most from Salt’s fallout. He and Gale Sondergaard had adopted two children; according to the 2000 feature One of the Hollywood Ten, which dramatizes the making of Salt, Joan Kirstine Biberman committed suicide when she was 19 and Daniel Hans Biberman disappeared.

[Source: amazon.com]

A People’s Classic for the Ages

The filmmakers may have lost in a court of law, but they won in the court of public opinion. Inspired by an actual strike, Salt of the Earth became a realistic record of resistance, triumphantly dramatizing issues of class war, unionism, police brutality, anti-racism and feminism.

It may have been restricted at home but was widely seen abroad. According to Bill Jarrico:

The Russians paid with potato flour [to distribute it in the USSR], which was sold to someone who had trouble getting rid of it. The Chinese couldn’t pay at all because of U.S. regs, but showed the film to absolutely everybody. Because of the wide distribution in China, my father said that Salt had probably been seen by more people than any other movie up till then.

Bosley Crowther [Source: en.wikipedia.org]

They shot a film about minority rights with an African American on their makeshift crew, which was unheard of then in lily-white Hollywood. Reviews were often positive and on March 15, 1954 Bosley Crowther wrote in The New York Times of “a union-sponsored film drama” that is “in substance, simply a strong pro-labor film with a particularly sympathetic interest in the Mexican-Americans with whom it deals. True, it frankly implies that the mine operators have taken advantage of the Mexican-born or descended laborers, have forced a ‘speed up’ in their mining techniques and given them less respectable homes than provided the so-called ‘Anglo’ laborers. It slaps at brutal police tactics in dealing with strikers and it gets in some rough, sarcastic digs at the attitude of ‘the bosses’ and the working of the Taft-Hartley Law…”

Crowther continued:

Michael Wilson’s tautly muscled script develops considerable personal drama, raw emotion and power… Miss Revueltas, one of the few professional players, is lean and dynamic in the key role of the wife who compels her miner husband to accept the fact of equality, and Juan Chacón, a non-professional, plays the husband forcefully. Will Geer as a shrewd, hard-bitten sheriff, Clinton Jencks as a union organizer… are excellent, too. The hard-focus, realistic quality of the picture’s photography and style completes its characterization as a calculated social document.

In 1954, Salt co-won the Crystal Globe, the grand prize for best film, at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia, where Rosaura earned the Best Actress award. In 1955, the Academie du Cinema de Paris awarded Salt the International Grand Prize for best film. Rosaura Revueltas won for Best Foreign Actress (her male counterpart was James Dean). Almost 40 years later, Salt was selected for the National Film Registry of the National Film Preservation Board (the Library of Congress is its parent) as one of 100 films to be preserved for posterity.

The 70th Anniversary Commemoration of Salt of the Earth

To pay homage to this remarkable union-sponsored 1954 film, children of those who made Salt will gather at an October 27 screening of the classic at Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum (WGTB) in L.A. County. Before the movie, they will hold a panel discussion and take questions afterwards from the audience at the amphitheater.

The scheduled participants include: Ellen Geer, WGTB’s Producing Artistic Director and daughter of Will Geer; Arthur Revueltas, nephew of Rosaura Revueltas; Heather Wood, granddaughter of Clint and Virginia Jencks; and Bill Jarrico, son of producer Paul Jarrico. The panel and Q&A are to be moderated by myself, film historian Ed Rampell. Ellen Geer also plans to reenact her father Will Geer’s 1951 testimony before HUAC. For details see: https://theatricum.com/salt-of-the-earth-screening/.

[Source: lucypr.com]

An exceptional independent film that went against the grain in so many ways, Salt of the Earth derived its title from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5-7, when Jesus told the multitude:

Ye are the salt of the earth… Ye are the light of the world.

Salt is arguably the crowning cinematic achievement of those talents who had been purged during the Hollywood Blacklist.

With limited resources and against all odds, they created one of the best films of the 1950s. It offers a tantalizing glimpse of what American culture could have been, if it wasn’t for the conservative cancel culture of the Hollywood Blacklist.

For most of Salt’s artists, particularly Biberman and Jarrico, it is likely the finest work they ever did, their masterpiece. It is an enduring testament to the class struggle that this cinematic sermon on the movie mount continues to stand the test of time and inspire moviegoers.