Ngo Dinh Diem, South Vietnam’s premier from 1954 to 1963, was a Cold War version of Volodymyr Zelensky, an American-subsidized ruler who was fawned upon by leading U.S. politicians and the U.S. media despite causing the ruin of his own country.

Lyndon B. Johnson at one point compared Diem to Winston Churchill—though privately admitted:

Shit, Diem’s the only boy we got out there.1

Diem’s disastrous rule set the stage for the escalation of American involvement in the Vietnam War. His repressive policies fueled the growth of the National Liberation Front (NLF) guerrillas—aka Vietcong—which U.S. troops were sent to fight against.

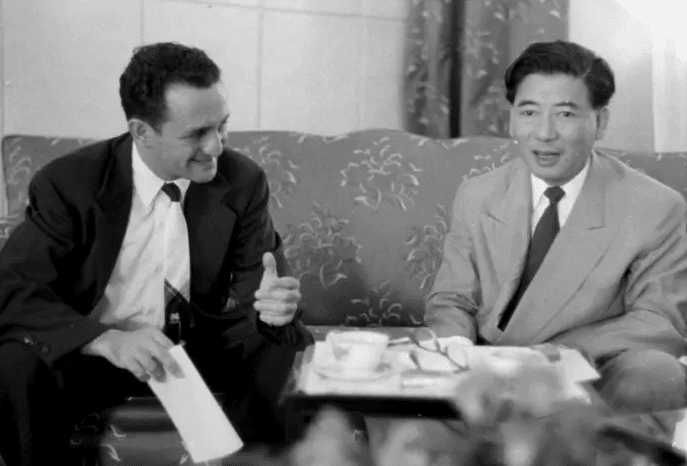

Wesley R. Fishel was a political science professor at Michigan State University (MSU) in the early 1950s, with a background in U.S. military intelligence, who developed a close relationship with Diem and served as a key lobbyist for him and liaison between him and the U.S. government. For many years, Fishel headed an MSU program that trained South Vietnam’s police to help bolster Diem’s regime and provided training to South Vietnamese civil servants in government administration.

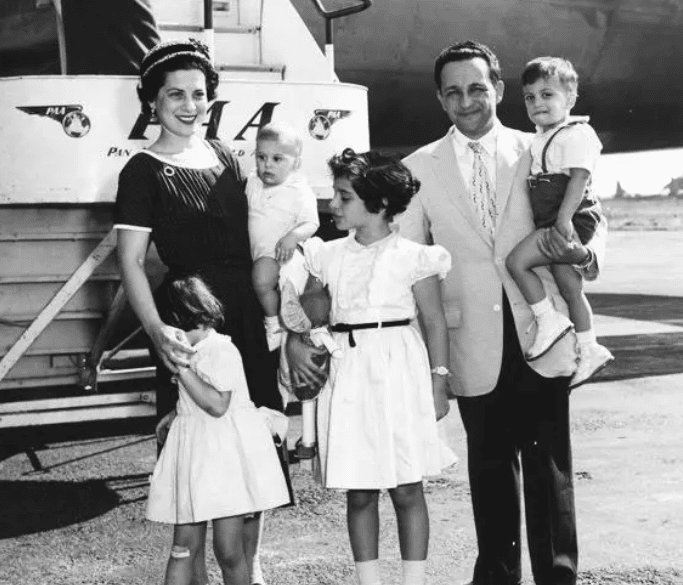

Fishel and his family en route to Saigon. [Source: goodreads.com]

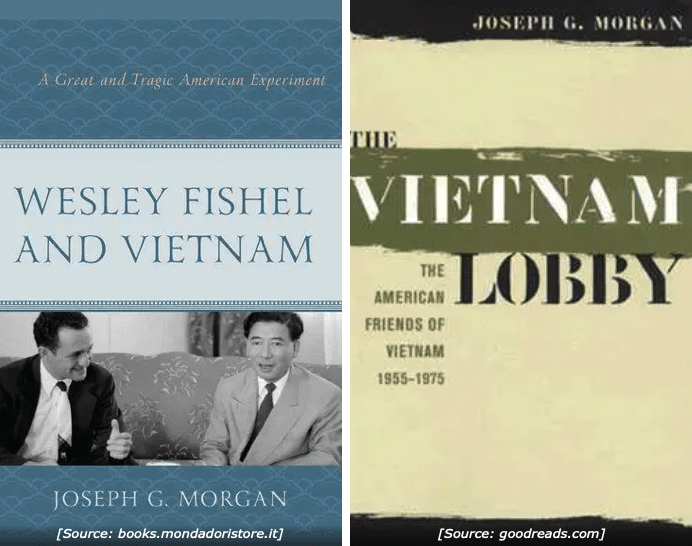

Fishel’s crucial role in leading the United States into the Vietnam War is chronicled in a book by historian Joseph G. Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam: A Great and Tragic American Experiment (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021).

Morgan is a historian at Iona University who previously wrote a book on the American Friends of Vietnam (AFV), a lobby group that Fishel helped found which supported expanded U.S. aid to Ngo Dinh Diem in the 1950s. Financed in part by the CIA, the lobby’s members included prominent political figures of the era, including John F. Kennedy.

Morgan wrote that the AFV “had a lot to do with getting the U.S. into the Vietnam War.” Besides lobbying for U.S. aid to Vietnam, it “created an ideological framework justifying America’s intervention in Vietnam and the Saigon government’s harsh treatment of political opponents as a necessary reaction to the communist menace.”2

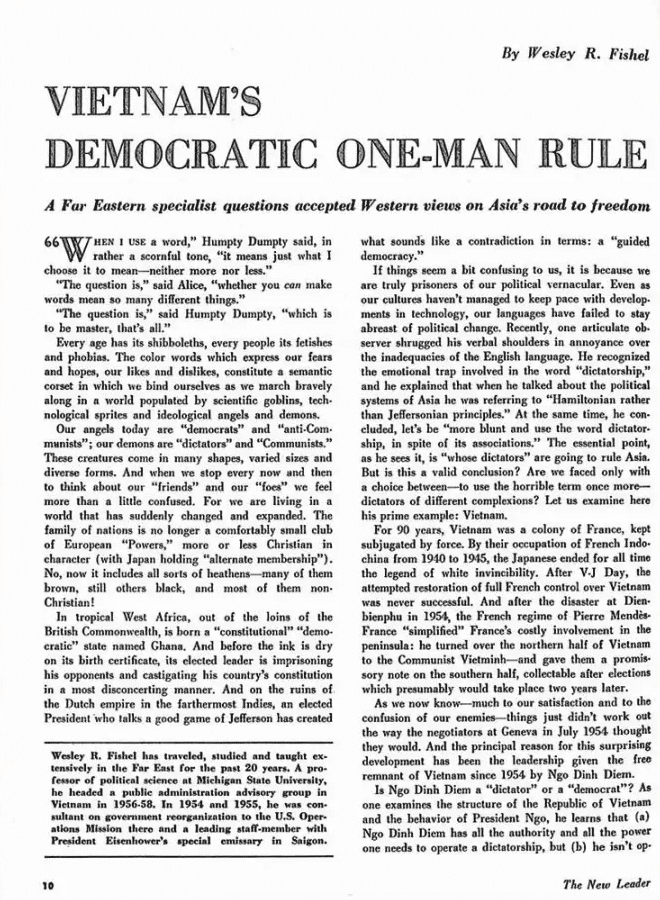

Fishel, identifying as a Cold War liberal, was a mover and shaker in the AFV. For most of Diem’s time in power, Fishel was his chief American publicist. He wrote many articles in prominent U.S. journals supporting him, including one in the CIA-subsidized liberal anti-communist New Leader with the tortured title “Vietnam’s Democratic One-Man Rule.”

In that piece, Fishel claimed that Diem enjoyed all the powers of a dictator but had chosen to rule democratically, establishing a government that “now is assuredly one of the most stable and honest on the periphery of Asia.”

Fishel went on to complain how many Western critics applied Western standards when “the people of Southeast Asia are not, generally speaking, sufficiently sophisticated to understand what we mean by democracy and how they can exercise and protect their own political rights.”3

These remarks reflected a blatant colonial mentality and provided an apologia for heavy-handed U.S. political interference in South Vietnam and Diem’s jailing and assassination of political opponents, some after he had passed a law that allowed for secret military tribunals followed by the death penalty.

[Source: flickr.com]

Stocky in build, clean shaven and short (he was 5’4” tall), Fishel grew up in a Jewish family in Cleveland, Ohio, in the 1920s and 1930s, and studied international relations at Georgetown and Northwestern with a specialty in Asian affairs.

In 1941, Fishel joined the U.S. Naval Reserve and began military intelligence training in Japanese languages, taking up a post as an analyst at the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean areas, where he worked under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz translating Japanese tactical documents and planting loudspeakers in front of Japanese positions at Iwo Jima in an effort to persuade the Japanese to surrender.

After the war, Fishel earned a Ph.D. in international relations at the University of Chicago where he wrote a dissertation on the termination of America’s extraterritorial privilege in China.4

In a 1950 essay published in The Western Political Quarterly, Fishel ironically stated that Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh had “severed his connection with international communism” and that his Viet Minh movement “reflected the strength of Vietnamese nationalism.”5

Fishel subsequently changed his view, however, in depicting Diem as a representative of a viable anti-communist nationalism that he believed the U.S. should try to nurture.

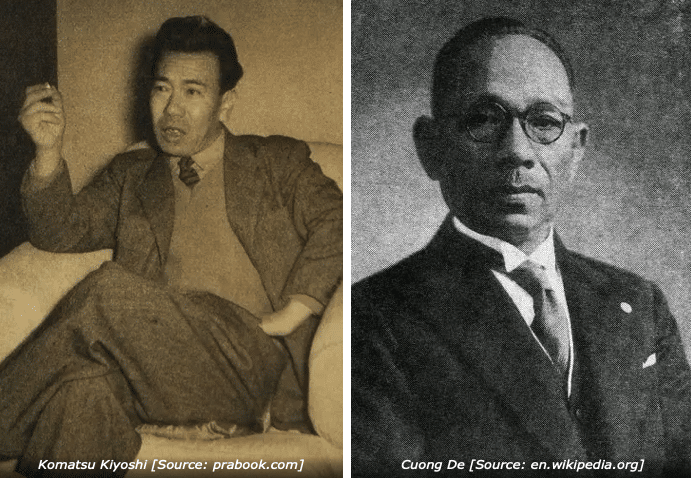

Fishel was introduced to Diem in Japan in 1950 by his mentor Komatsu Kiyoshi whom he met while participating in a UCLA program involving the education of U.S. military personnel based in Japan. Komatsu had written a book advocating for an independent Vietnam under Japanese tutelage and formed a close friendship with Cuong De, a member of the Vietnamese royal family who promoted an anti-communist alternative to the Viet Minh and knew Diem.6

Morgan points out that various historians suggest that Fishel was acting as an agent of the CIA in his initial meetings with Cuong De and Diem.7

Morgan states that Fishel is known to have willingly collaborated with the CIA and acted as an intelligence operative for the U.S. Army in the summer of 1950 when he was assigned as a lieutenant to the military intelligence section of the General Headquarters of the Far East Command.8

Fishel at this time carried out military assignments of a “secretive nature,” including reporting on the activities of Cuong De and Diem for U.S. intelligence.9

Dallas Coors of the U.S. embassy in Saigon referred to Fishel as the “source of the very interesting intelligence reports submitted by the Embassy in Tokyo of Prince Cuong De and his conversations with Bishop Thuc and Ngo Dinh Diem.”10

As Fishel progressed in his academic career, he received grants to carry out research for the U.S. State Department and military in the service of the Cold War on psychological warfare, information programs, and atrocity propaganda.

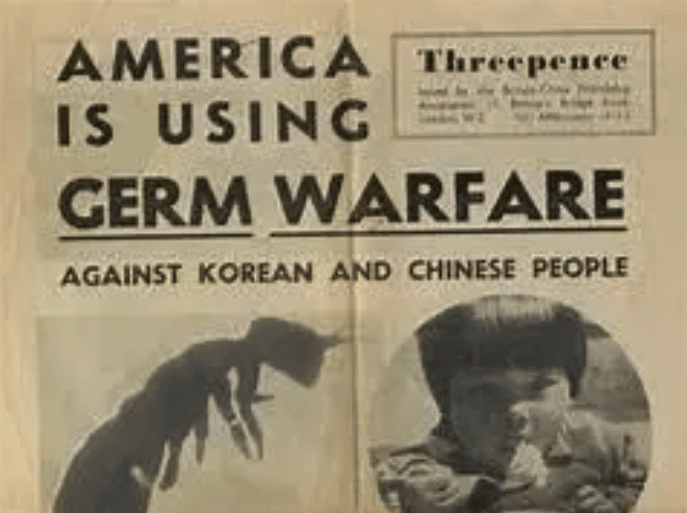

Morgan says that, in the early 1950s, Fishel approached the CIA about the possibility of compiling an annotated bibliography of material concerning the Chinese economy, and carried out a study of alleged communist atrocity propaganda accusing American forces of employing germ warfare in the Korean War—which recent historical investigations have shown to be true.

Fishel co-wrote an article with another MSU faculty member, Herbert Garfinkel, expressing doubt about the truth of the germ warfare accusations, falsely claiming that communist authorities refused to let outside groups enter their territory to judge the merits of their allegations.11

Fishel was involved in the cover-up of U.S. germ warfare in the Korean War. [Source: samim.lo]

Fishel became especially close to Diem after the latter became South Vietnam’s prime minister following his appointment by French puppet emperor Bao Dai and victory in rigged elections overseen by the CIA.

Vietnam was temporarily divided under the 1954 Geneva Accords—which the U.S. never signed—that called for elections in 1956. However, the Eisenhower administration never followed through on these elections because, as Eisenhower stated in his memoir, Ho Chi Minh would have received at least 80% of the vote.

As the U.S. pumped in millions of dollars in military and economic aid to try to entrench Diem’s rule in South Vietnam, Fishel served as Diem’s unofficial adviser, having breakfast with him and members of his entourage in the presidential palace many mornings.

Fishel worked out of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon with Edward Lansdale, another key adviser to Diem, who specialized in psychological warfare.

The MSU project that Fishel headed was publicly exposed in a 1966 Ramparts magazine article that was featured on the magazine’s cover with Madame Nhu—Diem’s sister-in-law and a power-broker in his regime—in an MSU cheerleader’s uniform.

After conducting interviews with disaffected MSU faculty members, notably economist Stanley K. Sheinbaum, Ramparts writers Warren Hinckle, Sol Stern and Robert Scheer displayed how Fishel and MSU had compromised their academic integrity by functioning as technical advisers and publicists for a sordid dictatorship that had come about because of the U.S.

Hinckle, Stern and Scheer quoted an MSU professor who said that Fishel was “the closest thing to a proconsul that Saigon had.”12

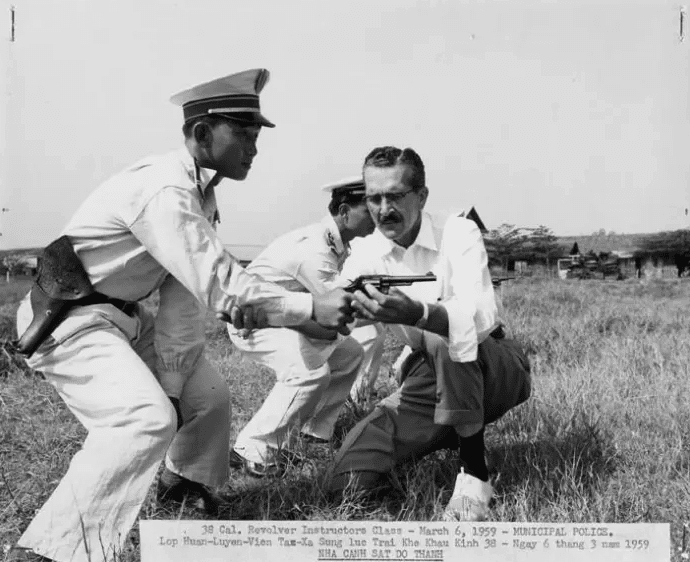

Most pernicious was the MSU police training program, which introduced new methods of fingerprinting, helped South Vietnam’s police force develop an identity card program to monitor political activity, and provided firearms and other policing technologies used in a repressive campaign against Diem’s opponents and the nascent guerrilla movement.13

The most controversial aspect of the program involved the university’s decision to allow CIA personnel to be hired as faculty to give counter-espionage and counter-insurgency training to the Sureté, a repressive personal instrument of Diem’s controlled by his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu.14

An Michigan State University Group adviser instructor helps a Vietnamese municipal police officer on his technique with a .38-caliber revolver, March 6, 1959. [Source: politico.com]

The use of the MSU program as a cover for the CIA had been set up by the White House15 and makes further clear Fishel’s CIA affiliation.

In a June 1961 article in The New Republic, “A Crumbling Bastion: Flattery and Lies Won’t Save Vietnam” two disaffected MSU faculty, Milton Taylor and Adrian Jaffe, charged that Fishel, as MSU’s chief adviser, lived extravagantly in Saigon in a pretentious home guarded by a sentry box and that served as a venue for hosting lavish parties.16

Fishel thus emerges as a character right out of Eugene Burdick and William J. Lederer’s novel, The Ugly American, which criticized Americans who lived like colonials in Third World countries and interacted mostly among themselves, causing them to become detached from the lives of the Third World natives they were supposed to be helping.17

The cruelty of Diem’s regime was detailed in accounts by Australian journalist Wilfred G. Burchett who quoted from Buddhist bonzes who described how Diemist forces imposing forced relocation edicts under the Strategic Hamlet program would enter their villages and demolished homes, killed the buffalo and pigs and beat up, imprisoned and tortured anyone who did not comply.

One bonze said that the so-called Vietcong (NLF) “existed because of the crimes of the Diemists” and were “our own people” who were “forced to take to the jungle to defend themselves…when they came to our villages at night for food, they would pay, unlike the Diemists who loot and kill.”18

Fishel himself began to break from Diem following the infamous Buddhist immolations in 1962 triggered by Diem’s savage repression of the Buddhists and Vietcong, or NLF.

Fishel was hired at this time by the Kennedy administration as a State Department consultant and supported the CIA coup against Diem, establishing lists of potential successors and making contacts with them.19

In March 1966, Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky awarded Fishel the Kim Khanh Medal, the Republic of Vietnam (RVN)’s highest civilian award for his “priceless effort to help Vietnam fight communism and ignorance and disease.”20

Nguyen Cao Ky [Source: en.wikipedia.org]

After returning to his teaching career at MSU, Fishel continued to advocate for greater American support in establishing a stable non-communist government in South Vietnam.

America’s departure from Indochina, he wrote in The Washington Post in June 1964, would “consign the Vietnamese, the Lao, and their neighbors to the limbo of Chinese domination for generations to come.”21

Fishel continued to attend AFV conferences in this period and aided in the publication of political pamphlets that it sponsored, including Problems of Freedom: South Vietnam Since Independence and Vietnam: Is Victory Possible?, and edited the book, Vietnam: Anatomy of a Conflict (Itasca, IL: F.E. Peacock Publishers, 1968), which was designed to counteract anti-war authors.22

According to respected correspondent Bernard B. Fall, Fishel’s writings included factual inaccuracies, expressed incredible naiveté about the relationship between the Saigon government and its people, and clashed with “everything credible written on the subject.”23

Edwin E. Moise, a Harvard student and future historian of the Vietnam War, condemned a letter signed by Fishel supporting the Vietnam War in The New York Times for “saying things that aren’t so” and for showing “devotion to the slogans and fantasies of national propaganda.”24

When the Johnson administration called for a domestic “counter-offensive on college campuses to combat the pacifist demonstrations,” Chester L. Cooper, the National Security Council official responsible for dealing with domestic reaction to the war, enlisted Fishel to defend Johnson administration policies at teach-in events.25

At the 1965 National Teach-in at the Sheraton Hotel in Washington, D.C., Fishel defended the legitimacy of the South Vietnamese state and expressed concern about the fate of the people of South Vietnam if the U.S. withdrew and the communists took over.26

Adopting a combative style, Fishel attacked critics of the war by declaring:

I find it difficult to understand why we are so eager to hand sixteen million people of the Republic of Vietnam [RVN] over to the communists.27

Fishel became a target of anti-war protesters when he returned to teaching at MSU and at Southern Illinois University (SIU), Carbondale, where he was hired to set up a Vietnam Studies center in 1969/1970 with a grant from USAID (MSU’s president from the 1950s, John Hannah, was then USAID’s administrator).28

Students would enter Fishel’s classes to heckle him, put up “wanted” posters indicting him for murder, and carried out a mock war crimes tribunal where students plastered a dummy of him with pies in the face after finding him guilty of crimes against humanity because of his support for Diem and the escalation of the Vietnam War.29

As part of his support for the war, Fishel was involved in a program to adopt a Vietnamese hamlet that would receive support from an American citizen—an idea conceived by Edward Lansdale, a master of public relations.30

Fishel had helped promote the original concept of “strategic hamlets,” whereby South Vietnamese peasants were located into hamlets policed by U.S. forces in an attempt to isolate the NLF, though the program had backfired as South Vietnamese peasants did not want to move from their ancestral lands and relief aid intended for the hamlets was often stolen by corrupt officers in the South Vietnamese army.

In defending U.S. policy, Fishel would often invoke his own expertise and that of other government-funded intellectuals, conveying his belief that “policy had to be made by experts” and that outsiders were not qualified to judge it.

Paradoxically, Fishel never developed fluency in the Vietnamese language and was derisive toward regular Vietnamese people, basing his perspective on the viewpoint of Washington insiders and members of Diem’s inner circle.

Fishel further had a child-like view of his own country’s supposed benevolence in foreign affairs, believing that American policy had been carried out in Vietnam with good intentions.

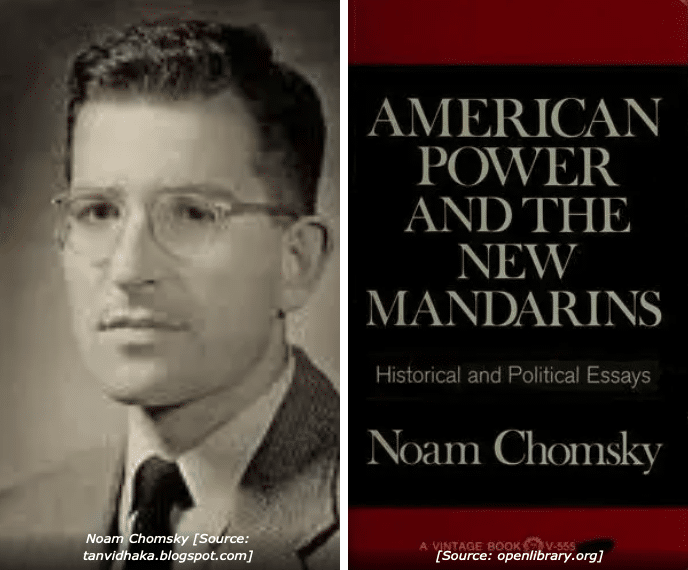

Noam Chomsky had Fishel in mind when he wrote a scathing indictment of American intellectual complicity with the Vietnam War, American Power and the New Mandarins(1967).

Chomsky wrote in the book that intellectuals are “in a position to expose the lies of government,” but “all too many gave it their service.”

Fishel was characteristic of the “scholar-experts” whose work in Southeast Asia reflected “the mentality of the colonial civil servant, persuaded of the benevolence of the mother country.” He and others like him were “frauds” who “did much to justify the application of American power in Asia, whatever the human cost,” according to Chomsky.31

Fishel remained a staunch apologist for U.S. foreign policy in the Vietnam War until the end, casting it as a noble attempt to halt communist aggression.

When President Richard Nixon ordered the famous 1972 Christmas bombing of Hanoi that killed thousands of civilians, Fishel described it as an example of “forceful persuasion designed to get communists back to the negotiating table.”32

Destruction rendered by Nixon’s 1972 Christmas bombing, which Fishel was unbothered by. [Source: politico.com]

By this point, many of the original supporters of the AFV had turned against the war and were dismissive of Fishel’s arguments in support of the war.

Gilbert Jonas, an aide to Diem and campaign staffer for John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential campaign who had been in the AFV, wrote that Fishel and others like him,

the guys who should’ve been critical, the academically trained ones, became totally uncritical, totally supportive without seeing what was going on, what was happening, right before their eyes, and that was a really bad thing for them and us, as a country and for Vietnam as a country.33

Unfortunately, today’s academic landscape is dominated by many clones of Wesley Fishel who vie with each other for government research grants and access to power, and uncritically align themselves with U.S. policy while denigrating its detractors in neo-McCarthyite terms.

Former U.S. Ambassador to Russia and current Stanford University Professor Michael McFaul comes to mind as a Fishel-type who serves as a publicist for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky while pushing a hard-line policy against Russia that has led to disastrous results.

One can only hope that a similar student awakening occurs as in the 1960s and that McFaul and his compatriots will be lampooned by a contemporary version of Ramparts, and hounded by anti-war protesters, as Fishel was.

Notes:

- ↩ Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: The Viking Press, 1983), 214.

- ↩ Joseph G. Morgan, The Vietnam Lobby: The American Friends of Vietnam, 1955-1975(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), x. According to Morgan, AFV members would attack critics of the Diem regime in McCarthyist terms. The AFV also campaigned for American investment in Vietnam.

- ↩ Joseph G. Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam: A Great and Tragic American Experiment(Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021), 87.

- ↩ Ibid., 9, 10, 11, 12, 13.

- ↩ Ibid., 14.

- ↩ Ibid., 15.

- ↩ Ibid., 16.

- ↩ Idem.

- ↩ Ibid., 17.

- ↩ Idem.

- ↩ Ibid., 21, 22. Fishel and Garfinkel wrote that confessions made by some American prisoners of war “are the most effective of the psychological warfare materials that the communists have aimed at the peoples of the United Nations and of neutral countries.” Fishel and Garfinkel’s article also referred to Soviet trials of members of Detachment 731 of the Japanese Kwantung army which carried out germ warfare and sadistic medical experiments on POWs in China. Fishel and Garfinkel asserted that Soviet charges were “regarded by most Western observers with some skepticism,” though they have been confirmed by recent historical scholarship. For refutation of Fishel and Garfinkel’s views, see Thomas Powell, The Secret Ugly: The Hidden History of U.S. Germ War in Korea(Sacramento, CA: Edgewater Editions, 2023).

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 44.

- ↩ Ibid., 62; Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation-Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012).

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 62. The CIA advisers included L. George Boudrias, a naturalized citizen from Quebec who had served in the Canadian army.

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 62.

- ↩ Ibid., 139. The authors never named Fishel directly but he was the Michigan State University Group chief adviser.

- ↩ William J. Lederer and Eugene Burdick, The Ugly American, rev. ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019).

- ↩ Wilfred G. Burchett, The Furtive War: The United States in Vietnam and Laos (New York: International Publishers, 1963), 7, 8.

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 83.

- ↩ Ibid., 131.

- ↩ Ibid., 112.

- ↩ Ibid., 113. Fishel also became head of the editorial board of Vietnam Perspectives, a pro-war journal intended to counteract the arguments of the Vietnam anti-war movement. In November 1966, he co-signed a statement published in The New York Times that charged that the Vietnamese communists had launched a war against a “truly Vietnamese nationalist regime…now fighting to maintain its independence” and which denounced academic critics of the war. Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 127.

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 140.

- ↩ Ibid., 127.

- ↩ Cooper is alleged to have worked for the CIA from 1947 to 1962.

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 120, 121.

- ↩ Ibid., 121.

- ↩ Journalist Mary McCarthy called Fishel one of these “paramilitary professors” and “Diem’s inventor.” She said that, under Fishel’s leadership, the CIA “virtually took over Michigan State University to train a Vietnamese police force and to form Vietnamese adept in political science and public administration.”

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 173.

- ↩ Ibid., 122.

- ↩ Ibid., 171. Chomsky considered Ithiel de Sola Pool, the chairman of MIT’s political science department, another prototype of the phony scholar-expert. Pool had been involved in student politics in the 1930s but formed close ties with U.S. officials in Washington during World War II and the Cold War and defended U.S. policies in Vietnam and other Third World countries.

- ↩ Morgan, Wesley Fishel and Vietnam, 185.

- ↩ Ibid., 211.