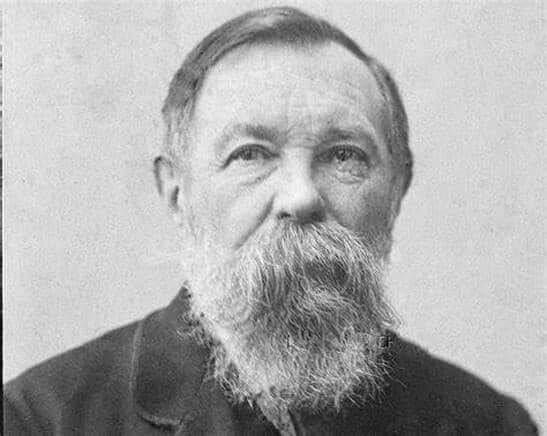

In 1876, Friedrich Engels made an important contribution to our understanding of the nature of human evolution, in an essay titled ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’ which was not published until 1925, as a chapter in The Dialectics of Nature. The essay is still worth reading, despite the massive advances in our knowledge of human evolution since both its publication and writing. Between those times, paleoanthropology had in fact disappeared up a blind alley, due to the 1912 discovery of the ‘Piltdown Man’ fossil, which was only finally debunked as a forgery in 1953. Scientists would, with the later discovery of different fossils of early humans, find their own way out of the Piltdown cul-de-sac, but the reasons why they would take decades to do so are illuminated by the insights in Engels’ original essay.

The central claim is one that is at the heart of Marxist thinking: that practical activity—labour—is the core human attribute, binding together the subjective and the objective. It was Marx’s original objection to existing materialist thinking, such as that of Feuerbach, that ‘the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively.’1 Labour is how we change the world around us, and simultaneously, dialectically, understand it; it is reflexive activity. Thus ‘Labour is the source of all wealth … next to nature, which supplies it with the material that it converts into wealth’.2

Engels builds from this proposition to argue that human evolution must have proceeded first from apes becoming bipedal, thus freeing the hands to be used for practical activity, rather than walking or grasping branches while climbing. Engels points out ‘the great gulf between the undeveloped hand of even the most man-like apes and the human hand that has been perfected by hundreds of thousands of years of labour.’3 Of course, we now know that it was not hundreds of thousands, but millions of years that separated the developed human hand from its ape-like ancestor, but Engels was working with the meagre knowledge of his time. And yet, his central contention has been borne out.

The consequence of this insight into the centrality of labour to human evolution is that human intelligence itself was the creation of labour; we first had to become creative, labouring animals before the human brain and intelligence could evolve. However, Engels also warned that our development ineluctably led to our privileging of the mind itself as the creator: human societies created ‘trade and industry, art and science’ and religion. All these things ‘appeared in the first place to be products of the mind and seemed to dominate human societies’ so that ‘the more modest productions of the working hand retreated into the background.’ This created the idealistic outlook, where the mental, or ‘spiritual’ is held to be the true origin of things, rather than practical activity. Thus Engels warned that ‘the most materialistic natural scientists of the Darwinian school are still unable to form any clear idea of the origins of man, because under this ideological influence they do not recognise the part that has been played therein by labour.’4

The Piltdown debacle

This was indeed ultimately the reason for palaeoanthropology’s greatest blunder; accepting as genuine the fraudulent Piltdown fossils. The model for human evolution current at the turn of the twentieth century was that the human mind, and therefore the brain, must have evolved first, since only the mind can drive progress. Therefore, when a fossil apparently combining an ape-like jaw (it was in fact an orangutan jaw) with a human cranium (a modern skull), both artificially stained to simulate great age, was found at a site in England in 1912, it fitted all the scientific expectations perfectly, down to the racist presumption that Europe, and best of all, England, was the perfect site for the human story to begin. Sophisticated dating techniques that could immediately have revealed the fraud were not yet available to palaeontologists. In the meantime, real discoveries of human ancestors, such as Homo heidelbergensis in Germany (now thought to be probably ancestral to the Neanderthals, and possibly to Sapiens as well), were dismissed as insignificant.5 Discoveries of Homo erectus in China and Indonesia were also slighted.

Although enthusiastically accepted as genuine, Piltdown Man gradually became an anomaly, as other early specimens of the human lineage were discovered. Among the most important fossils to be found was the ‘Taung child’ discovered in 1924 in South Africa. It is now known to be 2.3 million years old. The scientist who described the fossil skull, Raymond Dart, named a new species from it, Australopithecus africanus [southern ape of Africa], and claimed this small-brained creature was a human ancestor. Most eminent scientists rejected his conclusion at the time, not least because a number of them were fixated on the Piltdown specimen, and felt that the Taung fossil had to be a chimpanzee or gorilla ancestor. In the 1930s, more complete and adult remains of Austrolipithecus africanus were found, piling on evidence that this species was a small-brained bipedal hominin; not an ape, but an animal with some clear human physical characteristics.

It wasn’t until the 1940s that A. africanus was accepted as a part of the general human lineage, not least due to the efforts of a scientist who was also involved in the effort to debunk the Piltdown fossil, which was conclusively dismissed in 1953. However, the interpretation of A. africanus has a further lesson for the role of ideology in science. Raymond Dart interpreted broken animal bones found with A. africanus to be evidence of tool use and predation, and even cannibalism. On this basis, he developed a theory of human origins emphasising violence as the driver of evolution. The idea of the ‘killer ape’ became influential, particularly through Robert Ardrey’s popularising book African Genesis (1961). It is, of course, the theory behind the famous opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001, showing ape-like creatures discovering violence and tools simultaneously.

This all turned out, however, to be another blind alley in the quest to understand human origins. Subsequent careful analysis of the bones associated with A. africanus fossils showed that they had been chewed by leopards or other such predators. Poor little africanus, far from being a mighty hunter, was in fact the prey along with the other animal remains. The idea that A. africanus was tool using was also dismissed, although more recently, opinions are beginning to diverge again on that issue.

The species is also now not generally thought to be a direct human ancestor, but more probably on a related branch of the hominin family evolutionary bush. It may have been ancestral to a branch of hominins that were initially classed as ‘robust australopithecines’, and now often seen as an extinct genus of its own, Paranthropus. These were bipedal, almost gorilla-like hominins, with massive jaws and broad, flat teeth for chewing tuberous vegetation; a kind of human panda, if you like. Paranthropus species existed between 2.6 million and 600,000 years ago, alongside other hominins which led more directly to us. There are many different views on where A. africanus may fit in the increasingly bushy tree of human evolution. Nevertheless, the original idea of the most ancient ancestors of humanity being apex predators, or even particularly brainy, had crumbled in the face of accumulating evidence that they were at best, generalist scavengers and vegetarians at the mercy of Africa’s powerful predators.

Enter afarensis

In 1974, another crucial discovery was made when a team in the Afar valley in Ethiopia discovered a partial skeleton they named ‘Lucy’ (the Beatles album Sergeant Pepper was playing on a loop while the archaeologists worked on the fossils in camp in the evenings). At 3.2 million years old, this new species was considerably older than A. africanus, but similar in many respects. It was very short, with some ape-like features, in the length of its arms, for example, but was also clearly bipedal. ‘Lucy’ was soon recognised as a new species of Austrolipithecus, named afarensis after the area the fossils were found. A. afarensis was soon championed as the earliest discovered human ancestor, and a veritable ‘missing link’ between ancestral apes and the human lineage, although many scientists disputed the idea.

By this point, it was abundantly clear that bipedality had preceded the arrival of human-level brain size, and clear tool use, by some millions of years. During this time, bipedal hominins split into various different species with different survival strategies. There are perhaps as many as half a dozen or more recognised Australopithecine species, none of them appearing particularly reliant on developing brain capacity. It seems that around two million years ago, various Australopithecine and Paranthropus species, in addition to the early and fairly small-brained human Homo Habilis, were all living at the same time and in the same region. There is still considerable controversy over Australopithecines and their place in the human lineage, with some evidence that they may have been still partly arboreal. Even so, there is now a general consensus that Homo must have emerged from the Australopithecines.

Assessing the intelligence of these hominins is of course very difficult, once you move away from merely measuring cranial capacity. Tool use and especially their manufacture is generally accepted as a key criterion for human-like behaviour. The problem is that many tools can be made from materials that do not fossilise well or frequently, so palaeoanthropology has tended to focus on the appearance of stone tools, which certainly do require extensive planning and skill to make and use, but also survive easily and in plentiful numbers.

Tools and brains

Stone tools went through a number of stages of developing sophistication, but for a long time the earliest assemblage of stone tools was the Oldowan one, named after the Olduvai Gorge, where Louis Leakey first found them in the 1930s. The Oldowan technology began about 2.9 million years ago, and has generally been assumed to be associated with the earliest appearance of a Homo species in the fossil record, specifically Homo Habilis at 2.3 million years ago. This was a discovery by Louis’ son Richard Leakey, who, following the Leakey family tradition, insisted on its place in the human lineage. Nonetheless, there have been at points some doubts as to whether the species should actually be assigned to Australopithecus rather than Homo.

Oldowan-style tools were still being used by Homo species until at least 1.7 million years ago. However, it has never been entirely settled that early Oldowan tools were definitively or exclusively the product of Homo, rather than any contemporary australopithecine species. In 2022, however, an assemblage of stone tools dating to 3.3 million years ago was found at Lomekwi in Kenya, which show clear signs of intentional planning and varied processes and purposes involved in making the tools, unlike some other claims for very early tools. Although there is plenty of evidence of present-day apes’ tool use, the Lomekwian tools are clearly a significant level of sophistication beyond anything known from contemporary ape behaviour.

It remains a mystery what species of early hominin was responsible for the Lomekwian tools, although one possible candidate is the somewhat enigmatic Kenyanthropus platyops, found in the same region, and named in 2001 by Maeve Leakey (the wife of Richard Leakey). The Leakey superstar archaeological dynasty, in the past, has often rejected Australopithecus as a human ancestor, so the naming of this species as entirely separate from the former somewhat smacks of a family ideology. There is debate about whether K. platyops should in fact be classed as an australopithecine, or just possibly a very early iteration of Homo. Currently, the whole taxonomy of early hominins is entirely up in the air, with several pre-Australopithecine species having been discovered in the last thirty years, including a whole new genus, Ardipithecus, and deep uncertainty about the interrelationship of all these specimens.

However the classification of the increasing variety of early hominins plays out in the long run, it is now very clear that tool making, and presumably tool use preceding it, significantly predates the explosive growth in cranial capacity that came with the appearance 1.7 million years ago of Homo Ergaster (‘working man’), or Homo Erectus, depending on which flavour of hominin classification you prefer. Currently, H. Ergaster is considered to be the earlier African species, which then radiated out into Eurasia to become Homo Erectus, but in Africa eventually evolved into later Homo species including ourselves.

Hands for labour

In the end, remains of ancient tool can only get us so far, as they generally can’t be definitively linked to particular species (until much later on when Homo species made camps with fires, and the clear paraphernalia of living spaces). A different tack has been taken by a group of researchers recently, who subjected Australopithecine fossil hands, particularly their muscle attachment sites and internal bone architecture, to a battery of statistical comparisons in order to analyse their potential capabilities as rigorously as possible.6 They found that A. afarensis had a capacity for precision gripping, for example, within a range much closer to sapiens than apes, with A. africanus showing a more ambiguous set of traits. This suggests, but in no way proves, that A. afarensis does indeed belong on the human lineage, while A. africanus may not.

A later australopithecine, A. sediba also showed more human-like morphology. The authors conclude ‘our results suggest that A. sediba and A. afarensis habitually performed a suite of manual activities that were similar (yet not identical) to the power-squeeze grasping and in-hand manipulation patterns seen in later Homo.’7 Further, they bring us back to Engels’ original point: ‘The frequent activation of muscles needed to perform characteristic humanlike grasping and manipulation in these early hominins lends support to the notion that humanlike hand use emerged prior to and likely influenced the evolutionary adaptations for higher manual dexterity in later hominins.’

There is a twist with A. sediba, however, as no straightforward linear development between A. afarensis through A. sediba to Homo can be traced. A. sediba appears later on and in a different region from the earliest Homo specimens, so probably it is not a direct human ancestor. This raises the possibility (already suggested in other kinds of evidence) that there were other lineages than strictly our own one that were developing ever more sophisticated tool-use and behaviour. Evolution was no straight ladder of progress, but a much branching one full of a host of possibilities. As the radical evolutionist, Stephen Jay Gould was fond of pointing out, it was mere happenstance that our particular twig of the tangled bush of human evolution was the one that survived. Alternative histories where it was A. sediba that survived to propagate an entirely different line of creatures could just as easily have happened.

Labour, production and consciousness

Be that as it may, Engels’ 1876 essay raised another vital issue about human development. He traced our ancestors’ increasing ability to manipulate, and thus understand, the world around them until human consciousness developed, but from there society began to evolve its own dynamic. For all that we now regard many animals’ behaviour as far more sophisticated than the Victorians ever credited, Engels makes a still relevant distinction between human interaction with its environment and other animals: ‘the animal merely uses his environment, and brings about changes in it simply by his presence; man by his changes makes it serve his ends, masters it … once again it is labour that brings about this distinction.’8

Before rushing to condemn Engels here for the verb ‘masters’ and its implications, note that his argument moves directly on to precisely what is fatally problematic in humanities’ relationship with nature: ‘Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us.’ Engels goes on to detail a number of environmental disasters in human history, starting with deforestation in ancient Mesopotamia, the impacts of the same in Greece and Italy, and their serious consequences for climate and soil fertility: ‘Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature … but that we, with flesh, blood and brain, belong to nature.’9 Engels further argues that while it has taken thousands of years for us to learn ‘a little of how to calculate the more remote natural effects of our actions in the field of production’, the remote ‘social effects’ are still beyond our grasp.

To be able to ‘control and regulate’ the social effects of our labour, requires ‘a revolution in our whole contemporary social order’.10 In this peroration of his essay on labour and human evolution, Engels was sketching out a new phase of human evolution. Labour built the human species itself, and brought us into self-conscious purposefulness as a species, but we have not yet learnt to create societies which raise themselves to the same calculating self-consciousness of the human individual.

Thus our social production creates recurrent destructive effects, only some of which have we learnt to control. Engels couldn’t have known that capitalist industrial production would produce the terrible ecological catastrophe of global heating, with the potential to bring human civilisation, and even our species itself, to an end. Nevertheless, he was warning of the unforeseen consequences of our lack of self-conscious control over our own social production, and pointing towards socialist revolution as the only way to bring about a society which could regulate its relationship with nature. Human labour can only attain full self-consciousness, the promise of our evolutionary history, through socialism.

Notes:

- ↩ Kark Marx, ‘Concerning Feuerbach’, in Early Writings, intro. Lucio Colletti (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books 1975), p.421.

- ↩ Engels, ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’ in The Dialectics of Nature (London; WellRed Publications1964/1007), pp.172-186; p.172.

- ↩ ibid. p.173.

- ↩ ibid. p.180.

- ↩ Sarah Wild, Human Origins: A Short History (London: Michael O’Mara Books 2023), p.58.

- ↩ Jana Kunze, Katerina Harvati, Gerhard Hotz, Fotios Alexandros Karakostis, ‘Humanlike manual activities in Australopithecus’, Journal of Human Evolution 196 (2024), 103591.

- ↩ ibid. p.18 of 22.

- ↩ Engels, ‘Part Played by Labour’, p.182.

- ↩ ibid. pp.182-3

- ↩ ibid. p.184.