Joel Suárez is a long-time social activist and theologian who is part of the Martin Luther King Memorial Center in Cuba. This ecumenical organization promotes social participation and solidarity. In the interview, Suárez offers an intimate and thought-provoking perspective on Venezuelan former President Hugo Chávez’s spiritual trajectory, his first encounter with Fidel Castro, and his unique leadership style. Suárez also draws interesting connections between Liberation Theology and Chávez’s way of doing politics.

Cira Pascual Marquina: What is your first memory of Hugo Chávez?

Joel Suárez: I think my first recollection goes back to the 1992 civic-military insurrection, although my memory is blurry that far back. I do remember, however, that I was hopeful because I saw that it wasn’t a traditional right-wing putsch.

Nevertheless, my first important memory of Chávez is from 1994, when I was in Caracas on my way to Brazil. A group from the Martin Luther King Memorial Center and I were going to meet with the Landless Workers Movement [MST] and other grassroots organizations in Brazil. We were traveling with Viasa [Venezuela’s national airline, now Conviasa] and had to spend one night in Caracas.

I used the opportunity to get in touch with my Pentecostal brothers in Caracas, and they took me to a site linked to Chávez’s 1992 insurrection; I think we were in the “Cuartel de la Montaña” [now Chávez’s mausoleum]. The Pentecostal tradition puts much emphasis on prophecy, on the word that comes with the Spirit. That night, my brothers told me: Chávez is the man who will lead this country to the promised land. They used this biblical reference from the Old Testament, and they weren’t wrong.

Around that time my good friend Germán Sánchez Otero was in Caracas on diplomatic duty. He had had a clandestine meeting with Chávez and was very impressed. Germán was not someone who prophesised, but he told me that had great hopes for Chávez.

I see Fidel, too, as a kind of prophet. Chávez called Fidel “a Christian in the social sense.” I believe that Fidel had the Spirit talk to him and he received the same revelation about Chávez.

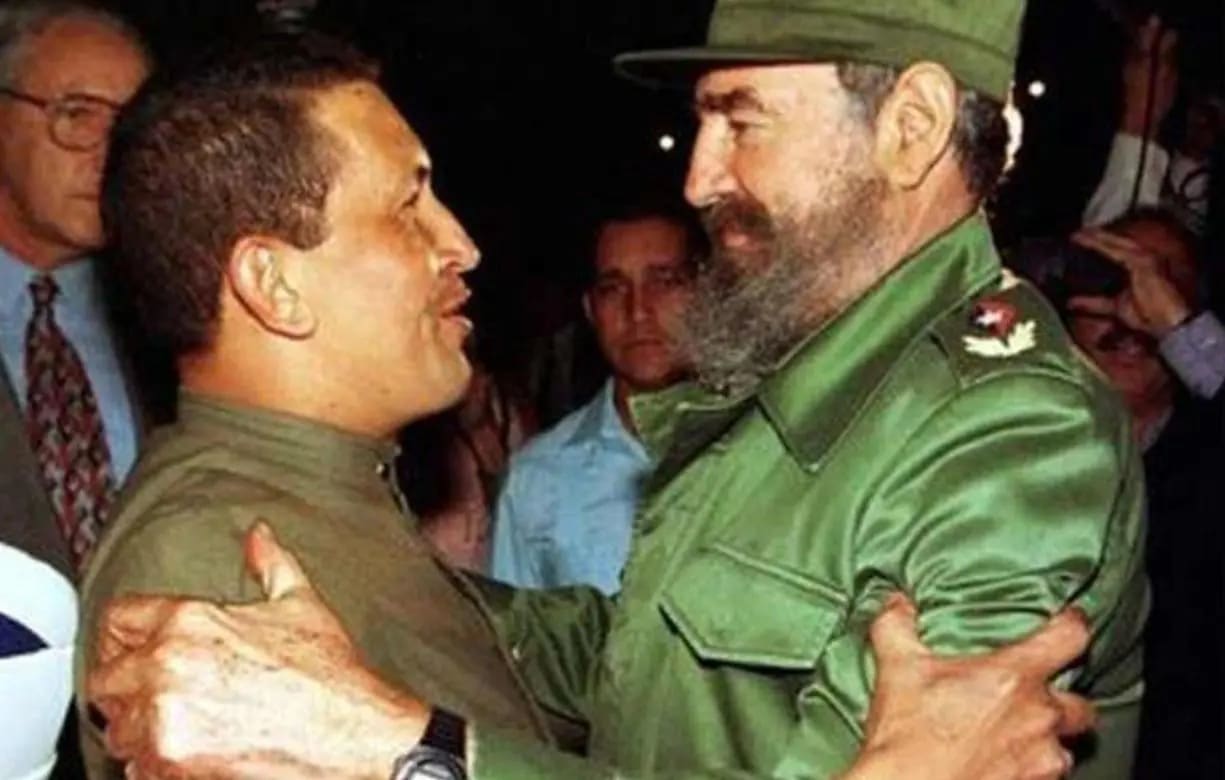

At about the same time, Eusebio Leal, the historian of the City of La Habana, invited Chávez to visit Cuba. We are talking about December 1994. Chávez’s visit was actually orchestrated by Fidel, as it quickly became publicly known.

The prophecy had spoken in Fidel’s heart, and he went to receive Chávez at the José Martí Airport [La Habana] as he would receive a head of state. That was the first time that Chávez and Fidel met. Even now, I am moved to tears thinking about that encounter.

Chávez and Fidel embrace in La Habana in 1994. (Archives)

CPM: This would have been around 1994, which was a kind of turning point in Latin American politics. Imperialism was advancing but at the same time, we saw various spakrs of resistance emerging.

JS: By 1994, neoliberalism had taken over most of Latin America, but resistance was growing. One of the most powerful expressions of resistance was the 1989 popular insurrection called the Caracazo, when working-class Venezuelans took to the streets and said ¡Ya basta! to the neoliberal policies that were creating death and devastation. I see this as a sign or prophecy of what was to come.

Bill Clinton launched the North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA] early that year. He then held that awful First Summit of the Americas in Miami in December 1994, where the idea of the FTAA was presented for the first time. The forming of a free trade zone for the whole continent—North, Central, and South—was of great concern to many grassroots organizations, trade unions, Indigenous movements, and churches. We knew it was urgent to confront a project that aimed to recolonize or neo-colonize Latin America by plunging the people into the absolute rule of the free market.

In contrast, 1994 was also the year when Chávez and Fidel met in La Habana, forming a bond that would eventually derail the FTAA in Mar del Plata when Chávez famously said: “¡ALCA al carajo!” [“To hell with the FTAA,” 2005].

CPM: Isn’t it true that Fidel had been attempting to resist the Free Trade Agreement for some time already?

JS: Yes, I remember that some years back Fidel had called us [Martin Luther King Memorial Center] and many other social and mass organizations in Cuba to tell us that we needed to confront the FTAA initiative together. That was because, if implemented, the free trade alliance would have terrible consequences for Cuba, which was then in a slow process of re-establishing relations with the rest of Latin America.

This effort culminated in the Hemispheric Encounter of Struggle Against the FTAA in 2001. The initiative had Fidel’s backing, but he wanted us, the Cuban social organizations, to be the hosts.

Fidel would always sit in the first row of these meetings and listen carefully to those presenting. He was intent on learning, but he was also discovering a new phenomenon in Latin America: the emergence of new, non-conventional popular movements.

In 2002, the same group of people gathered at the second meeting of the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil. That is where the action plan for the “Continental Campaign in the Struggle against the FTAA” was born. It happened in the heart of the MST.

Around that time, Fidel had learned that Chávez had signed the FTAA treaty in the Third Summit of the Americas [2001] with many reservations, and so Fidel began to conspire and organize a larger strategy of resistance around the continent.

Hugo Chávez in Mar del Plata, Argentina, in December 2005, when he symbolically declared the FTAA’s death. (AFP)

CPM: The struggle against the FTAA got a platform in the World Social Forum [WSF], which came to Caracas in 2006, just one month after Chávez had made public his anti-FTAA stance. You were among the promoters of the Caracas WSF. Can you tell us more?

JS: I was part of a commission that first explained the WSF philosophy to Chávez. We understood that the project had certain limits, because it tended to separate social movements from governments. However, we pointed out that having 80 to 100 thousand people coming into contact with the Bolivarian Process would be a real benefit for the revolution. Chávez agreed.

The WSF was held in Caracas in January 2006. When it was about to conclude, I was with a team of presidential advisors on a bus; one of them got a call and passed me the phone… it was Chávez on the other end of the line!

In this phone call, Chávez asked me about my father, a Baptist pastor and a representative in Cuba’s Popular Power National Assembly. Then, out of the blue, suddenly, as a man of faith would do, Chávez said to me: Greet your father and ask him to pray for me because I’m losing my voice and have to talk to thousands of people very soon. He wanted my dad to pray for him!

That is how something became evident to me that had been revealed to many others before: in Chávez the revolutionary and the spiritual realms were not separate. However, I will add something else: while Chávez belonged to the Christian tradition, he assumed his faith in a heterodox manner. His was an open spirituality, the spirituality of the journey. He was a voracious reader inspired by many different texts and ideas; he was heterodox in that sense, but he was orthodox in the literal sense of the word: he went to the root principles and teachings.

It is important to point out that Chávez was not dogmatic, because when orthodoxy is dogmatic it can conflict with orthopraxis [correct conduct]: that would be to put right belief above right action. If that occurred, then a dogmatically understood teaching could enter into conflict with the action of a community that challenges oppression. That’s why I say that Chávez was not dogmatic.

CPM: Can you explain this further?

JS: Chávez’s radicality lay in his understanding of the need to anticipate and materialize the revolutionary imaginary in the present, which coincides with the perspective of Liberation Theology. His practice involved bringing the revolutionary horizon into present work, even if that can only be done in a fragmentary way. Yet it is in those very shards and fragments that life must be invested. This approach was deeply operative in him.

In any case, this is my speculation; it would need further documentation, but this is how I have come to understand the question of spirituality in Chávez.

The biblical phrase “By their fruits, you will know them” was fundamental for Chávez. This is why his ethical and radical adherence to principles—and to the ethic that sustains them—was always linked to an orthopraxis that anticipates and verifies the future we desire, dream of, and work toward. Interestingly, Chávez’s practice can also be anticipated in the verses of Alí Primera and in the songs of the Latin American campesino masses.

Finally, I have another related reflection: Chávez understood that Christian testimony derives from an Aramaic word that means “martyrdom.” For him, testimony was not just words—it was the tangible result of belief, of revolutionary faith, a faith nourished by his religious upbringing. Implicit in Chávez’s testimony, in his long and marvelous speeches, is the notion of martyrdom, which serves as evidence of what one confesses to believe.

Perhaps I’m doing a bit of Chavista theology here, but perhaps not.

It is undeniable that there was a spiritual connection between Chávez and the Venezuelan pueblo. (PSUV)