A few days before Remembrance Day, November 11, 2024, the Government of Canada announced that it will not release that portion of a report produced by the Commission of Inquiry into War Criminals in Canada (Deschênes Commission) that names 900 Canadians accused of war crimes committed on behalf of the Nazis.

Canada admitted these people and others after the Second World War, including many former members of the Waffen SS Galizien (Ukrainian).

We then learned that it was Global Affairs Canada which prevented Library and Archives Canada (LAC) from granting an access to information request to make these names public. According to the LAC spokesperson, the decision to keep the list sealed “was based on concerns regarding risk of harm to international relations.”

The Globe and Mail, which along with others filed the access to information request, explained the decision this way:

Global Affairs has repeatedly warned about Russian President Vladimir Putin using disinformation to justify his invasion of Ukraine.

Remembrance Day? Or Suppression of Remembrance Day?

Should we remind Global Affairs Canada that during the Second World War, these 900 people were fighting for the Nazis, and therefore against our parents and grandparents! Do we have to inform them that 1.2 million Canadians fought against the Nazis, 45,000 of whom never returned?

Fortunately, there are authors and journalists who are keeping a close eye on things, one of whom is Peter McFarlane, author of the excellent new book, Family Ties: How a Ukrainian Nazi and a living witness link Canada to Ukraine today (Toronto: James Lorimer, 2024).

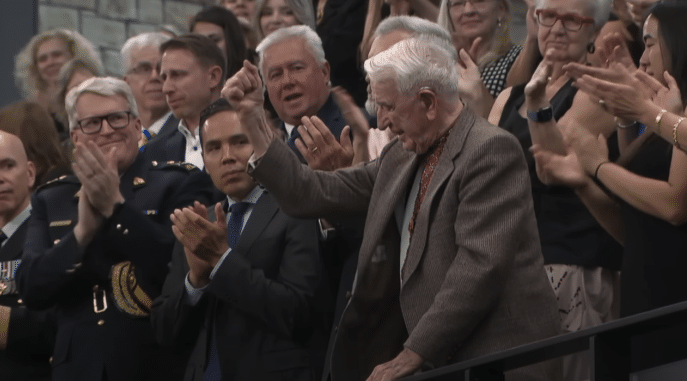

McFarlane’s starting point is the double ovation the Canadian parliament granted former Waffen SS Galizien member Yaroslav Hunka in September 2023—a shining case of Canadian governmental amnesia.

But above all, it was the hearty applauding Chrystia Freeland, former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance of Canada and current Member of Parliament with the Liberal Party, whose grandfather, Mykhailo Chomiak, was a Nazi collaborator. Though Freeland cannot be held responsible for her grandfather’s crimes, she could at least recognize them and distance herself from them, which she has never done.

Canada’s parliament applauds Yaroslav Hunka, a former member of the Waffen-SS. Canada’s then-Chief of Defence Staff General Wayne Eyre is on far left. [Source: wsws.org]

Volodymyr Zelensky and Justin Trudeau join a standing ovation for the Nazi veteran. Chrystia Freeland is in the blue blazer. [Source: independent.co.uk]

The author follows the journey of two families from the same region of Ukraine, then known as Galicia, who arrived in Canada in the wake of the Second World War.

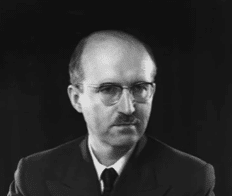

On one hand, there is the family of Mykhailo Chomiak, who was the editor of the Ukrainian-language Nazi newspaper Krakivski Visti from 1940 to 1945. This newspaper, which had nothing to envy from Der Stürmer, promoted Adolf Hitler, the Nazis, the SS and, in particular, the Waffen SS Galizien (Ukrainian) and their murderous campaign against Jews, the “Judeo-Bolsheviks,” the Poles and all those they considered subhuman.

Chrystia Freeland’s grandfather Michael Chomiak at a party—he is to the right of the man smoking a cigarette. In the lower right corner of the photo in uniform is Emil Gassner, the Nazi administrator in charge of the press for the region. [Source: theprogressreport.ca]

In parallel, McFarlane traces the journey of Montreal writer Ann Charney, born Ann Korsowar in Brody in 1940, a city northeast of Lviv in western Ukraine, and very close to the birthplace of the Chomiak family. Brody was a small town of about 24,000 people, 40% of whom (about 10,000) were Jews when Ann Charney was born.

Family Ties is divided into three parts. The first, entitled “Murder in Galicia,” covers the history of Galicia up to 1945 where Lviv (Lemberg, Lwow, Lvov—depending on the period) is the most important city. It was while traveling in the region for a book on another subject that the author developed this part of the story, with the help of, among others, members of the Chomiak family who had remained there after 1945.

The second part, “The Most Ukrainian of Countries,” focuses on Canadian citizens of Ukrainian origin, their deep political divisions, and their role in the politics of their country of origin and of Canada since 1945, again with the families of Mykhailo Chomiak and Ann Charney as a common thread.

The third part, “The Return of the True Believers,” concentrates mainly on the last ten years, showing in particular how the past, especially from the 1920s to the 1950s, has shaped today’s politics in both Ukraine and Canada. This part also includes a trip to Ukraine (to Lviv, Brody, and elsewhere) in 2022, after the war with Russia began.

The contrast between the two families’ stories is striking. Through his research, travels and interviews, the author allows us revisit the birth and development of the murderous fanaticism of the former, who chose to join Hitler’s hordes. He also has the reader grasp the terror suffered by millions of Jews, Poles, Russians, anti-fascist Ukrainians, and anyone who refused to adhere to the Nazi ideology.

For example, the author, who visited all the places inhabited by both, demonstrates how comfortable Chomiak lived from 1940 to 1945, especially in Krakow, the capital of the Nazi-occupation government of Poland. This comfort is illustrated in terms of the salary he was paid to edit the Nazi newspaper Krakivski Visti and the offices and equipment needed to do this work, which were confiscated from Jewish owners, but also his lodgings, seized from a Jewish family whose “filth” and “vermin” Chomiak complained about to his German employers.

Nazi parade in Stanislav, Ukraine, in 1943. [Source: dailymail.co.uk]

In contrast, Ann Charney, her mother Dora, and her aunt Regina took refuge during the war in a barn loft a few kilometers from Brody. For two-and-a-half years, they could only rarely leave their hiding place, fearing death at the hands of German soldiers or Ukrainian collaborators, who were sometimes their neighbors from Brody. They were at the mercy of Manya, a Ukrainian woman who, in return for a few pieces of bread, extorted from them everything they had brought with them in terms of money or jewelry.

Liberated by the Red Army and in particular by a young soldier named Yuri in the summer of 1944, they could barely walk due to extreme hunger and atrophied muscles. Ann was four years old.

Peter McFarlane was inspired by Ann Charney’s memoir Dobryd (Brody) first published in 1973 (published in French in 1996) and compared by critics to that of Anne Frank. Unlike what she calls “the Holocaust industry” or “Holocaust porn,” Ann Charney, an award-winning Montreal writer and journalist, refuses to stoop so low. For her, that way of approaching these crimes dehumanizes the victims by making them objects, when there are verifiable facts and where ordinary humans attack other ordinary humans.

In Brody, the German army and the Ukrainian militias first rounded up all the Jews in a ghetto surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by Ukrainian collaborators, often residents of Brody themselves. Then came deportation, in particular to the first Nazi extermination center in Belzec, northwest of Lviv, which Heinrich Himmler established in early 1942.

Ann, her mother, her aunt and her cousin managed to escape the ghetto and take refuge in the barn in time to avoid the fate of the others. They were thus among the 88 survivors of Brody, out of a Jewish population of nearly 10,000 in 1939.

“So they exited our history”

The two visits that Peter McFarlane made to the Museum of History and Local Lore in Brody are the most revealing as to both what happened at that time and the current state of mind of many Ukrainians in that part of the country. McFarlane describes his arrival at the Brody Museum in 2022 as follows:

The road to Brody was a memory lane for the SS Galizien….there is a roadside chapel surrounded by five hundred white crosses that Ukrainian SS veterans had erected in 1994 as a memory to their comrades who had fallen in the battle of Brody….

Of the current exhibits, he adds:

They were much the same as the previous year—still with the final room celebrating the Galizien division with photos and weapons and uniforms and maps from the battle of Brody. They had added a photo of Yaroslav Stetsko and included his declaration of independence of Ukraine ‘under the leadership of Adolf Hitler.’

Yaroslav Stetsko [Source: uinp.gov.ua]

A damning portrait of Canada

The journey of these two families during and after the war and their arrival in Canada presents a damning portrait of Canada and of the leaders of the Ukrainian Canadian community, many of whom were also Nazi sympathizers and with whom the Canadian government worked at the time. The fact is that Canada rolled out the red carpet for thousands of Nazi collaborators, including Mykhailo Chomiak.

At the same time—and this makes the portrait all the more damning—Ottawa was subjecting real refugees from the Nazi war to a cruel obstacle course as they sought to immigrate to Canada. That was the case of Ann Charney and her family.

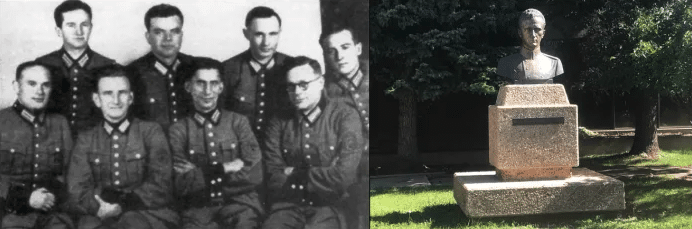

Monument in Edmonton to Nazi soldier Roman Shukhevych who is second from left among his SS Battalion. [Source: forward.com]

The criticism of Canadian policy does not stop there. In a clear, factual and hyperbole-free style, the author demonstrates how Canada has pursued, to this day, a policy of support for this fringe of Ukrainians who today openly and proudly herald and emulate fighters of the SS Galizien and who are very influential in the current government in Kyiv.

Family Ties is a remarkable book on a period of history—the Second World War, before and after—that continues to haunt us. It is also a powerful antidote to Canadian amnesia and especially to the attempts to rewrite the history of that war to justify the warmongering provocations of Washington, Ottawa, London, Paris and other NATO countries.