In Venezuela’s Amazonas state, fishing has long been not just a trade but a whole way of life rooted in collaboration, knowledge sharing, and mutual aid. Now, under the U.S. blockade, fishing has become an even more important source of food. At the same time, traditional fisher people’s cooperative way of working has proven useful in solving blockade-induced obstacles.

The following study looks at the Ayacucho Commune, which is based on fishing, located in Amazonas capital city, Puerto Ayacucho. The Ayacucho Commune is an expression of the impressive synergy between a longstanding cooperative way of life, on the one hand, and a nation-wide communal movement aimed at socialism, on the other.

The Ayacucho Commune comprises both Indigenous and criollo (non-Indigenous) fisherpeople. Their stories in this three-part series shed light on how fisher people are working together to build self-government and break their dependency on the capitalist market, while promoting food sovereignty in the region.

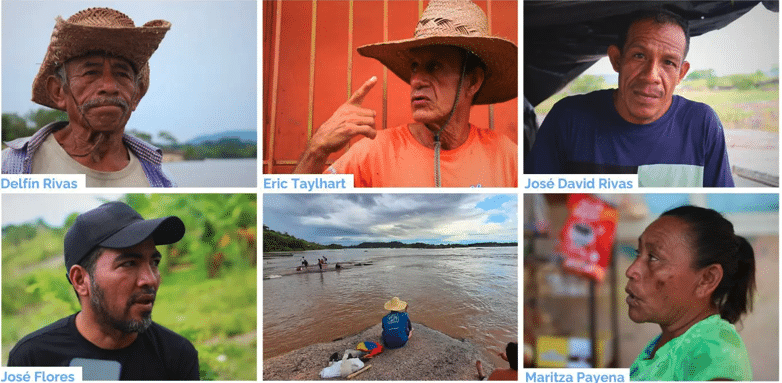

Delfín Rivas is a 73-year-old fisherman and a promotor of the CONPPAs (fishers’ councils) | Eric Taylhardt is a housing spokesperson at the Ayacucho Commune and a CONPPA member | José David Rivas is a young fisherman who began learning the trade when he was 9 years old | José Flores is the state coordinator of fisher people for the Ayacucho Commune | Maritza Payena is a fisherwoman and a spokesperson for the Bagre Communal Council. (Rome Arrieche)

The commune

With some 6,000 residents, the Ayacucho Commune brings together six communal councils located on the eastern shore of the Orinoco River.

José Flores: The Ayacucho Commune began coming together around the fishing communities of Puerto Ayacucho back in 2009, when Chávez began to talk about communal organization. As fisherpeople with a long tradition of cooperation, the Comandante’s call inspired us immediately.

Our commune’s full name is “Multiethnic Pluricultural Agro-Productive Ayacucho Commune” because not only are we fisherpeople, but we are also a multiethnic community that brings together criollos [non-Indigenous] and Indigenous peoples who keep their languages and many of their traditions alive. The Indigenous communities in the commune are Huo̧ttö̧ja̧, Kurripako, and Jivi.

Eric Taylhardt: The commune is the foundation of daily life here. It’s where we address pressing issues and organize to find solutions. As in any commune, our communal councils have several committees, including education, healthcare, and finances, but we also have fishing committees. That is one of the virtues of the Law of Communes [2010]: it allows each commune to define its committees according to its particular characteristics. Chávez was a visionary.

The fishing committees of our communal councils interlink with the CONPPAs [fishers’ councils], of which there are six in our commune, and with the larger Communal Fishing Circuit, which brings together five communes engaged in fishing in and around Puerto Ayacucho.

The Fishing Circuit is still in the making, but it will be a game changer, because it will help us increase our production, which will in turn contribute to regional food security. In these times of blockade, in Amazonas, as in the rest of the country, food insecurity remains the primary social issue.

The Circuit’s main goal is to break the dependency with the capitalist intermediaries. Every day we wake up very early to go fishing, sometimes risking our lives, but the intermediaries are the ones who profit from our work because they have the infrastructure to take the catch to the market. This must stop, and we know we can do it hand in hand with the government. The solution? Building a communal refrigeration storage facility.

José Flores: Fishing is more than just work for us; it’s a way of life that binds the community together. Families gather along the Orinoco River daily, sharing stories while tending to their nets and boats. It’s through these moments that we build connections, not only to the river that sustains our lives but also to one another. Fishing isn’t just about providing food; it’s also about preserving our way of life in Amazonas.

Eric Taylhardt: The Ayacucho Commune has become a reference in Puerto Ayacucho, inspiring communal organization in other communities. Each commune is different, but we all share the same goal: improving everyone’s quality of life. As it turns out, communes are key to this.

While the U.S. economic blockade has hurt every Venezuelan and some people have focused on individual solutions, it is more clear every day that coming together is the only way for the working class—campesinos, fisherpeople, factory workers, etc.—to live with dignity, in a sovereign country, and in peace.

José Flores: In our commune, we have areas known as “Indigenous territories,” which are home to Huo̧ttö̧ja̧, Kurripako, and Jivi communities. These territories are deeply tied to our roots. In my case I am criollo, but my ancestry is Indigenous.

Indigenous communities live by their own rules and rely on fishing, farming, and hunting to survive, while criollos often mix fishing with commercial activities. In our commune, many indigenous people also work as nurses, teachers, or doctors, adapting to urban life while preserving many of their traditions. When it comes to fishing, their techniques aren’t so different from ours—they use atarrayas [cast nets], just like we do.

Off to fishing in the early morning. (Rome Arrieche)

Fishing along the Orinoco River

The anecdotes told by Ayacucho communards treat various aspects of their craft and of a mode of life deeply intertwined with the river.

THE LIVES OF TWO FISHER PEOPLE

Delfín Rivas: I’m 73 years old and started fishing with a canalete [paddle canoe] when I was a kid.

Life as a fisher on the Orinoco River is not for the faint-hearted. The currents are strong, and one has to be careful to avoid the rocks. We lose people every year. Yet, amidst the challenges, there is undeniable beauty. As the sun goes down in the evening, the river turns red and the bushes on the riverside hum.

On our long nights fishing, the camaraderie among us fishers keeps the spirit alive; we share stories, advice, and a sense of solidarity that only those who face the river’s risks can understand. This is not an easy life, but it’s a free one. There’s no clock to punch, no boss looking over our shoulders—just our friends and the hope of a good catch.

Yesterday, I left home at 11 am, and here I am, nearly 24 hours later, still at it. I work with a simple laminated boat and a small 15-horsepower outboard motor that’s fuel-efficient—a real blessing when fuel is hard to get. I also have a 40-horsepower motor, but it’s been out of commission for ages. Finding the parts to fix the motor has been difficult and the cost keeps climbing. It’s not just me; many fishers are in the same situation, struggling with old tools and scarce resources. But we make do because the river provides.

Maritza Payena: There aren’t many women fishers, but I’ve been at it for 20 years—enduring rain, sun, and long nights. It’s a tough life, but it’s also beautiful.

Uncertainty defines our lives. The river can be bravo [wild], taking a friend one day, stingy the next, sending you home practically empty-handed, but it can also be generous, offering a good catch for ten days in a row. The ribazones [peak fishing seasons] organize our year: bocachico in July and August, blancopobre in February, palometa in September, and bagre [catfish] in December.

Still, being a fishing family isn’t just about going to the river. We weave our atarrayas [casting nets] with nylon because buying them is too expensive, and we’re always mending them. That’s why, when you walk through the streets of our communal council, you will see people sitting on the front porch talking to family and friends while working on their nets.

It’s hard work, but a quiet night on the boat and a good catch make it all worth it.

The day’s catch. (Rome Arrieche)

THE TRADE

José Flores: Our commune is predominantly a fishing community, although many families also tend to small conucos [subsistence farming plots], mostly for self-consumption. We learned the trade of fishing from our parents and grandparents, and we also learned to care for the land with them.

The majority of the fishing is done with atarrayas. This is the most common practice because the currents make other methods less practical.

Some mid-scale fishers use “bongos” [bigger boats with motors] while smaller fishers use “curiaras” [dugout canoes]. In the Orinoco we catch bocón, payara, bocachico, dorado, and bagre.

The bounty provided by the river defines the life in our community.

José David Rivas: Fisherpeople and their families weave their atarrayas, which is the method we use most often, but we also use “espileo,” which is a line with multiple hooks thrown into the river to catch several fish at once. There’s also fishing with buoys, which are used to catch larger fish.

José Flores: The main port in the commune is located in the area of the Bagre Communal Council, and most of the fish harvested is taken to land there. That port is also a hub for other activities, including vendors who sell fish and other goods, women selling fried fish, and people looking for work. Bagre Port is the center of our community’s economic activity.

Delfín Rivas: We make our own atarrayas and boats. As poor fisherpeople, we try to gain autonomy from capitalists to acquire our inputs. This is perhaps why our community is highly collaborative.

The intermediaries are an obstacle for us, the daily heartbreak for every poor fisher. Without cold storage, we depend on them to get our catch to the market, but their practices are exploitative and extremely harmful to our community. They pay us almost nothing for our catch.

But we don’t give up, just like our parents didn’t give up, and we have the tools—the river, our trade, and the commune—to go forward.

Mending the nets is a daily activity. (Rome Arrieche)