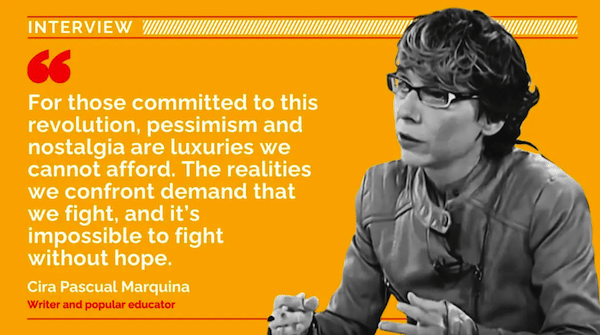

In this interview for the Cuban magazine La Tizza, VA’s Cira Pascual Marquina talks about the commune as the path and the end-goal for Venezuela’s socialist project. She also delves into Venezuela’s conjuncture after President Maduro assumed his third term on January 10th.

* * *

La Tizza: How does Cira Pascual Marquina identify: as an internationalist, a communard, an art curator…? And why do you identify this way?

Cira Pascual Marquina: I would identify as Venezuelan at heart, as part of the Bolivarian Process and a member of the Alexis Vive Patriotic Force—an organization that promotes communalization in our country—, as a popular educator, and as a militant researcher.

Why do I identify this way? I came to Venezuela inspired by the transformative power of the Bolivarian Revolution, which reactivated the principles of Bolivarianism throughout our continent, Nuestra América, while later advocating for socialism. This resurgence emerged at a time when the narrative of the “end of history” was practically hegemonic, implying that a socialist future would never be possible.

Our revolution reignited the socialist horizon around 2005-2006, but it had already defined itself anti-imperialist. This movement is not merely for a patria chica [small homeland]; it is for a Patria Grande [Great Homeland].

I identify as a popular educator because I co-founded Escuela de Cuadros [Cadre School] with Chris Gilbert—a self-managed space for studying and debating Marxist theory from the Global South. Additionally, I am privileged to be part of El Panal Commune in 23 de Enero, a vibrant barrio in Caracas known for its history of rebellion and grassroots activism. There, I contribute to the Pluriversidad Patria Grande, our communal seedbed. Alongside Chris, I also engage in militant research, working with various communes in a testimonial project where communards share their experiences and reflections, and theorize about communal construction in a nation besieged by U.S. imperialism.

Communards build their communes through self-organization, embodying the “participatory and protagonistic democracy” proposed by Chávez in The Blue Book [1991-1992]. This form of direct democracy began to take shape in the early days of the Bolivarian Revolution through initiatives like the Technical Water Tables and the Urban Land Committees—spaces that were fundamentally assembly-based. In 2006, these experiences culminated in the establishment of Communal Councils, which are also assembly-driven organizations focused on addressing specific community issues. In 2009, Chávez introduced the concept of the Commune, representing not just the aggregation of various Communal Councils into one unit, but a significant leap forward in creating an effective space for socialist direct democracy. This space aims to foster new social relations through collective management and usufruct of the means of production.

In recent years, my militant work has been framed around the communal project, which is both the end and the means for socialism in Venezuela.

Violent protests following the presidential elections on July 28. (teleSUR)

LT: The inauguration of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro took place on January 10. The mainstream media anticipated a climate of tension, instability, and polarization during that period. Did this prediction come true?

CPM: In the days leading up to January 10, not only was the mainstream media beating the drums of war, but those committed to the Bolivarian Process were also on high alert. Since the elections in July, right-wing factions, fascist elements really, and their bosses in the United States have made concerted efforts to undermine our process of popular sovereignty. This sabotage has been ongoing since the Revolution’s inception, but the threats intensified after July 28.

Indeed, mainstream media aligned with capitalist interests were crafting narratives that hinted at “violent solutions.” Following July 28, a climate of violence was fostered in the streets of Caracas and other regions; it was clearly orchestrated from abroad. Tragically, two Chavista comrades were murdered simply for their beliefs, others died in the clashes, and many who openly identify as Chavistas faced threats. This situation is not unprecedented; we experienced similar challenges during the fascist insurrections of 2014 and 2017, which we refer to as “guarimbas.”

As January 10 approached, we were genuinely concerned that a right-wing insurrection—ultimately fascist, pro-imperialist, and anti-democratic—might emerge to impose the absolute dictates of capital and its imperialist backers. Chavismo was on high alert.

Fortunately, those days turned out to be surprisingly calm. On January 9, the more radical factions of the opposition called for a street demonstration that, according to drone footage, attracted only about two thousand people at most. This event marked the “return” of María Corina Machado, a leader of the radical opposition and a puppet of imperialism. Despite a media spectacle filled with quickly debunked lies, the opposition showed little strength. In contrast, we witnessed large marches where the people rallied to defend the Bolivarian Process and President Nicolás Maduro.

In the end, those days were intense and actually joyful. However, we have not won the war; imperialism and capitalist interests will continue to operate against us through every possible means, just as they have with the Cuban Revolution since its inception.

However, I believe that our movement, committed to the defense of popular sovereignty, has emerged from this moment with renewed strength for societal transformation. We recognize that attacks will persist and may intensify, but the Venezuelan people—those aligned with the revolution and the process of change—have shown their capacity, conviction, and determination to defend themselves. Thus, while we have not won the war, the events of January 9 and 10 can be seen as a victory: we won this battle.

We are happy with this outcome, but we remain committed to radicalizing the Bolivarian Process and creating conditions for the communal project—ultimately striving for communism to materialize through the direct participation of the people, paving the way for new horizons of collective emancipation.

LT: President Maduro outlined seven lines of transformation for the 2025-2031 period in his inaugural address, alongside a proposed constitutional reform. What do these transformations entail, and why are they necessary today?

CPM: For nearly a year, President Maduro has been working on and talking about a roadmap for the Bolivarian Process, referred to as the 7Ts: The Seven Transformations. The first T is economic transformation, which we interpret as the reorganization of social relations of production. However, the enunciation is rather broad, so we must critically engage with its content.

The second T focuses on full independence, emphasizing the need to build cultural, scientific, educational, and technological sovereignty based on the Bolivarian doctrine we inherited from Comandante Chávez.

The third T addresses internal and territorial security, which is closely tied to the issue of sovereignty—particularly crucial for a nation besieged by U.S. imperialism.

The fourth T involves the renewal of the socialist model, which focuses on the need to define our path toward socialism given our concrete reality. We propose that the commune be central to this “renewal.”

The fifth T is the policy of inclusion and participation, which should aim to strengthen participatory democracy while, we would argue, promoting gender inclusion, sexual diversity, and comprehensive anti-racist policies.

The sixth T is ecological transformation. Many of these transformations, including this one, stem from Commander Chávez’s Homeland Plan. Ecological transformation is an urgent matter and requires immediate action, as capitalism threatens life itself. We believe that reorganizing production and consumption to address the climate crisis can only be achieved through a socialist and communal framework.

Within the logic of capital, it is impossible to effectively respond to a crisis generated not by humanity but by the capitalist system.

The seventh T focuses on geopolitics. Since the beginning of the Bolivarian Revolution, Chávez advocated for participation in a world system not dominated by U.S. imperialism and its European allies. The seventh T continues this tradition and aligns with national liberation movements in the Global South.

While these seven transformations are important, I would say that the constitutional reform proposed by President Maduro is perhaps even more critical. Why is this reform necessary?

Since 2009, the Commune has been interpreted as the path and destination for building socialism. Although the Bolivarian Revolution declared itself socialist in 2005-2006, we had not discovered yet how to get there. In his Aló Presidente Teórico 1 [2009], Chávez emphasized that the commune should be the central pillar in the reorganization of society. The Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela centers the principle of participatory and protagonistic democracy in its preamble, which, if fully realized, aligns with our vision of the Commune. The Commune embodies a collaborative and cooperative approach that prioritizes the socialization of goods and wealth, ultimately leading to a substantive democratization of all aspects of life. However, while the Constitution’s preamble hints at the Commune, it is not explicitly mentioned. Given the Bolivarian government’s shift toward the communal, it is essential to reform the Constitution to clearly incorporate the Commune in the text.

As Marxists and revolutionaries, we recognize that laws alone do not transform society; it is through class struggle that human beings create change. However, we also understand that legal tools can be of help in transformative processes. The “Law of Communes” and the “Laws of Popular Power” have been crucial tools for advancing along the communal path that Chávez proposed starting in 2009.

It is important to note that the Commune not only represents a communist alternative to wage exploitation, which was overcome in the Soviet Union, but also offers a means to transcend the metabolism of capital.

Chávez, in a rich dialogue with Hungarian philosopher István Mészáros, incorporated critiques of the Soviet project in his reflection. Mészáros argued that while private property over the means of production—and thus wage exploitation—was abolished, the despotic and authoritarian structures characteristic of capital remained intact. Needless to say, from the USSR we learn both from its virtues and its shortcomings. The Commune aims to fully achieve substantive democratization—not only in politics but also in the economy.

This is why President Maduro’s proposal for a constitutional reform centered on the Commune is so vital.

A communal assembly in Petare, Miranda state. (Communes Ministry)

LT: One of the key elements of Hugo Chávez’s vision was the concept of communes and communal power, encapsulated in the motto “¡Comuna o Nada!”, what significance does the communal space hold for the Bolivarian Revolution, and how do you perceive it today?

CPM: Chávez began discussing socialism around 2005-2006, but it was not until 2009 that he proposed the idea of the Commune. From that moment forward, the Commune became the strategic horizon and the path toward collective emancipation. While Chávez’s thought and the Bolivarian Revolution encompass many powerful ideas, such as Bolivarianism and a vision of emancipation from the Global South, I would argue that the Commune represents the synthesis of all these ideas, making its “discovery” a watershed event in the Revolution.

The importance of the Commune for the Bolivarian Revolution is immense. It embodies the realization of the Revolution’s goals and can also shed light on other processes of change and revolutions worldwide. The concept of the Commune, however, is not solely Chávez’s invention; it has historical roots in other revolutionary movements. For instance, communes played a pivotal role in the Chinese Revolution, and communal forms were significant in the revolutionary struggle against imperialism in Vietnam.

Closer to home, the idea of the Commune resonates deeply within the Latin American context. Many Indigenous societies in our continent have historically lived communally, and some still do. This is not mere speculation; I have seen it firsthand in Huo̧ttö̧ja communities in the state of Amazonas [southern Venezuela], where property remains collective, work is organized cooperatively, and surplus is not individually appropriated.

If we look at the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes, we find that ayllus were also communes. Similarly, in resisting colonialism, cumbes, quilombos, and other maroon communities organized outside colonial oppression. There, property was collectively held and decision-making followed non-authoritarian, assembly-based methods.

When we discuss communes, we not only honor Chávez but also draw from historical and contemporary forms of organization that enrich communal construction today.

In present-day Venezuela, there are cultural habits that contribute to communal construction, as is likely true in any vibrant society. For example, the practice of the sancocho—a community event where neighbors gather on Sundays to cook a stew and each contributes a different ingredient—exemplifies this spirit of cooperation. Additionally, the Indigenous practice of the cayapa is alive and well. The cayapa is a collective initiative to tackle specific problems, such as cleaning streets or repairing roads or schools. These practices are deeply embedded in Venezuelan culture and play a vital role in fostering communal bonds.

Moreover, one of the worst insults in Venezuelan culture—beyond cursing someone’s mother—is to call someone “pichirre,” meaning selfish or stingy. This speaks of the cultural emphasis on generosity and mutual support, which is essential for communal organization. Strengthening these cultural practices and imaginaries is crucial for building communes, as they serve as guiding lights for the future.

When we think about the Commune, we should consider forms of reorganization rooted in history and existing cultural practices, but we do not seek to return to the past. The Commune must integrate science and technology and it cannot simply be an “alternative.” Instead, it should be the epicenter of our efforts and must take command of the economy to become hegemonic.

One of the communal initiatives that President Maduro is promoting is the communal consultation. There were two in 2024 and there will be six in 2025. (Communes Ministry)

LT: In your opinion, did the communal space experience neglect at any point during Nicolás Maduro’s presidency?

CPM: When Barack Obama declared Venezuela an “unusual and extraordinary threat” in 2015, a series of unilateral coercive measures were unleashed against the country and its people, plunging Venezuela into a dramatic crisis. The blockade is a war without bombs.

The Cuban people understand this well: the blockade’s impact on health, the psychological toll, the loss of lives, and the families forced to leave their homeland… As the blockade intensified, the government implemented some liberal measures, such as eliminating price controls.

It’s crucial to note that Venezuela, as Chávez would often remind us, is not socialist, but certain containment mechanisms had been established. Many of these barriers fell under the pressure of the imperialist blockade. In the face of the devastation caused by the coercive measures, the government initially paid little attention to the communal aspect, focusing instead on promoting economic recovery within the existing system.

Interestingly, during those challenging years—which sentenced so much of the elderly population to death and individuals with chronic illnesses lacked essential medications —, in the time when there was almost nothing, the pueblo began to place their bets with the commune.

Chávez proposed the Commune in 2009 during a peak commodities period when the government was able to address pressing needs through its control over oil revenues. As a result, while the proposal for the Commune was positively received and many communes were established, the urgency for communal organization was not so felt.

By 2017, however, at a time of profound crisis, the communes began to resurge. The blockade’s violence forced the government to make concessions to capital, but it also catalyzed the pueblo’s return to the communal project.

More recently, since 2022 and especially in the past year, the government has shifted its focus back towards the Commune. I believe President Maduro recognized the exhaustion of the previous model, listened to the people, and initiated a pivot toward communalization—a shift that strengthens the connection between the government and the pueblo and recharges Chavista morale.

Chávez’s vision for the Commune was never about autonomy; he always emphasized that communes should grow in a collaborative relationship with the government, which should not only support them but also generate the material conditions for the creation of communal social property enterprises.

In summary, during the hiatus imposed by the blockade, there were some tensions between the government and the communal movement. However, in recent years, we have witnessed a beautiful shift toward rebuilding relationships and affinities. It’s important to note, however, that there was never a rupture between the communal movement and the Bolivarian government. No popular organization engaged in meaningful work ever proposed a break; instead, there were moments of critical dialogue, and the government listened.

The communal movement wholeheartedly supports and celebrates this reorientation, which ultimately represents a victory for the pueblo.

LT: As an internationalist of European origin, what is your perspective on the positions of “the left” in the West regarding the current situation in Venezuela?

CPM: I want to start by acknowledging that many leftist organizations and countless comrades around the world support the processes of change and revolutions happening in Latin America.

However, there is also a segment of the left that is strikingly Eurocentric. These individuals often measure what is unfolding in Venezuela with their own measuring stick made back home. They ignore our unique history, the war the Venezuelan people are enduring, our status as a dependent country, and the specific dynamics of oil rentierism. In essence, many Western “leftist” organizations fail to grasp the realities we face in Latin America—realities that are, in part, a direct consequence of colonialism and the ongoing mechanisms of wealth extraction from the Global North.

Consequently, we encounter interpretations that are not only limited but also excessively pessimistic—so much so that they dismiss our efforts to build a better society against all odds. Some even claim that popular power and the communal movement are merely co-opted by the government or opportunistic. In their view, our movement lacks agency and the capacity for independent thought and action.

Yet, for those of us living here and committed to this revolution, pessimism and nostalgia are luxuries we cannot afford. The realities we confront—the dependency of our economy and the constant imperialist aggression—demand that we fight, and it is impossible to fight without hope. Moreover, we have a historical foundation and a roadmap, which is no small achievement. For the Venezuelan people, to fail is simply not an option.

When observers from the North analyze the situations in Venezuela and Cuba, their first step should be to understand where and with whom the people striving for a socialist alternative—communal in our case—are. If they do this, they will recognize that something extraordinary is happening here. Is it perfect? No, it is rife with contradictions. But is it worth supporting and committing to it? Absolutely. If one identifies with substantive justice, is anti-imperialist, and opposes capitalism, failing to support the Bolivarian Process—its government and its communal movement—would be a grave mistake.

LT: What can the Venezuelan communal experience teach anti-capitalist movements around the world?

CPM: As I mentioned earlier, the Commune is not an invention of Chávez or the Venezuelan people; it is inherent to humanity. The Commune embodies a way of living fully and in community, free from exploitation, oppression, and domination. It is the space where self-emancipated individuals can thrive.

I firmly believe that the Commune has much to offer to the global communist movement. It provides a framework not only for overcoming wage exploitation but also for addressing the myriad of issues—the disasters—that accompany the logic of capital. This encompasses alienation and the various forms of oppression, including despotism, characteristic of the capitalist system.

The dehumanization inherent in capitalism, which objectifies individuals, can only be resolved through collective, communal, and cooperative efforts.

Importantly, in Venezuela, the Commune is not just a utopia; there are numerous thriving communes today. Within these communes, we see new ways of understanding politics and the emergence of new social relations. Communes are a window to a future that is already unfolding.

Even amid the worst crisis our country has faced, existing communes have provided effective responses to the needs of the people. For instance, during the most challenging years, El Panal Commune organized planned food distribution to ensure that everyone had access to basic staples. In many cases, communes democratically decided to address urgent needs by allocating part of their production surplus to purchase medicines or support families who had lost loved ones and could not afford funeral services. This demonstrates the communes’ ability to respond swiftly to the pressing issues in their communities.

Thus, the Commune is an extraordinary space—one that opens the door to a truly human future while also offering practical solutions to the problems people face today. This is why it is essential to understand the Commune and other experiences of building popular power, as they provide valuable insights on advancing the path of Revolution.

Hugo Chávez began to talk about communes in 2009. (Communes Ministry)