Matt Taibbi, once a populist writer who criticized big banks (Rolling Stone, 4/5/10; NPR, 11/6/10), has aligned himself with Texas Republican Sen. Ted Cruz, the kind of slimy protector of the ruling economic order Taibbi once despised. Putting his Occupy Wall Street days behind him, Taibbi has fallen into the embrace of the reactionary Young America’s Foundation. He recently shared a bill with other right-wing pundits like Jordan Peterson, Eric Bolling and Lara Logan. Channeling the spirit of Richard Nixon, he frets about “bullying campus Marxism” (Substack, 6/12/20).

Meanwhile, Glenn Greenwald, who helped expose National Security Agency surveillance (Guardian, 6/11/13; New York Times, 10/23/14), has buddied up with extreme right-wing conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, notorious for falsely claiming that the parents of murdered children at Sandy Hook Elementary were crisis actors. That’s in addition to Greenwald’s closeness to Tucker Carlson, the ex—Fox News host who has platformed the white nationalist Great Replacement Theory and Holocaust revisionism.

Owned (Hachette, 2025), by Eoin Higgins, traces the relationship between tech industry barons and two former left-wing journalists.

This is just a taste of what has caused many former friends, colleagues and admirers to ask what happened to make these one-time heroes of left media sink into the online cultural crusade against the trans rights movement (Substack, 6/8/22), social media content moderation (C-SPAN, 3/9/23) and legal accountability for Donald Trump (Twitter, 4/5/23).

Both writers gave up coveted posts at established media outlets for a new and evolving mediasphere that allows individual writers to promote their work independently. Both have had columns at the self-publishing platform Substack, which relies on investment from conservative tech magnate Marc Andreessen (Reuters, 3/30/21; CJR, 4/1/21). Greenwald hosts System Update on Rumble, a conservative-friendly version of YouTube underwritten by Peter Thiel (Wall Street Journal, 5/19/21; New York Times, 12/13/24), the anti-woke crusader known for taking down Gawker.

High-tech platforms

Some wonder if their political conversion is related to their departure from traditional journalism to new, high-tech platforms for self-publishing and self-production. In Owned: How Tech Billionaires on the Right Bought the Loudest Voices of the Left (2025), Eoin Higgins focuses on the machinations of the reactionary tech industry barons, who live by a Randian philosophy where they are the hard-working doers of society, while the nattering nabobs of negativism speak only for the ungrateful and undeserving masses. Higgins’ book devotes about a chapter and a half to Elon Musk and his takeover of Twitter, but Musk is refreshingly not the centerpiece. (Higgins has been a FAIR contributor, and FAIR editor Jim Naureckas is quoted in the book.)

The tech billionaire class’s desire to crush critical reporting and create new boss-friendly media isn’t just ideological. Higgins’ story documents how these capitalists have always wanted to create a media environment that enables them to do one thing: make as much money as possible. And what stands in their way? Liberal Democrats and their desire to regulate industry (Guardian, 6/26/24).

In Higgins’ narrative, these billionaires originally saw Greenwald as a dangerous member of the fourth estate, largely because their tech companies depended greatly on a relationship with the U.S. security state. But as both Greenwald and Taibbi drifted rightward in their politics, these new media capitalists were able to entice them over to their side on their new platforms.

Capitalists buying and creating media outfits to influence policy is not new—think of Jeff Bezos’ acquisition of the Washington Post (8/5/13; Extra!, 3/14). But Higgins sees a marriage of convenience between these two former stars of the left and a set of reactionary bosses who cultivated their hatred for establishment media for the industry’s political ends.

Less ideological than material

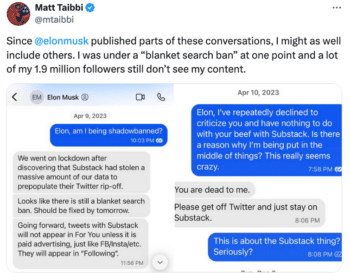

Matt Taibbi (X, 2/15/24) learned the hard way that cozying up to Musk and “repeatedly declining to criticize” him was not enough not avoid Musk’s censorship on X.

Higgins is not suggesting that Thiel and Andreesen are handing Taibbi and Greenwald a check along with a set of right-wing talking points. Instead, Higgins has applied Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s propaganda model, which they used to explain U.S. corporate media in Manufacturing Consent, to the new media ecosystem of the alt-right.

Higgins even shows us that the alliance between these journalists and the lords of tech is shaky, and the relationship can be damaged when these tech lords are competing with each other. For example, right-wing multibillionaire Musk bought Twitter, eventually rebranding it as X. Taibbi, who boosted Musk’s takeover and the ouster of the old Twitter regime, chose to overlook the fact that Musk’s new regime, despite a promise of ushering in an era of free speech, censored a significant amount of Twitter content. Taibbi finally spoke up when Musk instituted a “blanket search ban” of Substack links, thus hurting Taibbi’s bottom line. In other words, Taibbi’s allegiance to Musk was less ideological as it was material.

Greenwald and Taibbi have created a world where they are angry at “Big Tech,” except not the tech lords on whom their careers depend.

Lured to the tech lords

Owned addresses the record of these two enigmatic journalists, and their relationship to tech bosses, in splendid detail. In what is perhaps the most interesting part, Higgins explains how these Big Tech tycoons originally distrusted Greenwald, because of his work on the Snowden case. Over time, though, their political aims began to align, forging a new quasi-partnership.

As the writer Alex Gendler (Point, 2/3/25) explained, these capitalists are “libertarians who soured on the idea of democracy after realizing that voters might use their rights to restrict the power of oligarchs like themselves.” Taibbi and Greenwald, meanwhile, became disaffected with liberalism’s social justice politics. And thus a common ground was found.

As the lawyer for a white supremacist accused by the Center for Constitutional Rights of conspiring in a shooting spree that left two dead and nine wounded, Glenn Greenwald said, “I find that the people behind these lawsuits are truly so odious and repugnant, that creates its own motivation for me” (Orcinus, 5/20/19).

In summarizing these men’s careers, Higgins finds that early on, both exhibited anger management problems and an inflated sense of self-importance. What we learn along the way is that there has always been conflict between their commitment to journalism and their own self-obsession. We see the latter win, and lure our protagonists closer to the tech lords.

Higgins charts Greenwald’s career, from a lawyer who ducked away from his duties to argue with conservatives on Town Hall forums, to his blogging years, to his break from the Intercept, the outlet he helped create.

We see a man who has always had idiosyncratic politics, with leftism less a description of his career and more an outside branding by fans during the Snowden story. Higgins shows how Greenwald, like so many, fell into a trap at an early age of finding the soul of his journalism in online fighting, rather than working the street, a flaw that has forever warped his worldview.

Right-wing spirals

The book is welcome, as it comes after many left-wing journalists offered each other explanations for Taibbi and Greenwald’s right-wing spirals. Some have wondered if Greenwald simply reverted to his early days of being an attorney and errand boy for white supremacist Matt Hale (New York Times, 3/9/05; Orcinus, 5/20/19), when he used to rant against undocumented immigration because “unmanageably endless hordes of people pour over the border in numbers far too large to assimilate” makes “impossible the preservation of any national identity” (Unclaimed Territory, 12/3/05).

Higgins gives us both sides of Greenwald. In one heartbreaking passage, he reports that Greenwald’s late husband had even tried to hide Greenwald’s phone to wean him off social media for his own well-being.

In a less sympathetic passage, we see that of all the corporate journalists in the world, it is tech writer Taylor Lorenz who has become the object of his obsessive, explosive Twitter ire. Her first offense was running afoul of Andreessen, one of Substack’s primary financers. Her second was investigating the woman behind the anti-trans Twitter account, Libs of TikTok (Washington Post, 4/19/22).

In Taibbi, we find a hungry and aggressive writer with little ideological grounding—which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, except that it leaves one vulnerable to manipulative forces. Higgins shows us a son of a journalist who had a lot of advantages in life, and yet still feels aggrieved, largely because details of his libidinous proclivities in post-Soviet Russia made him vulnerable to the MeToo campaign (Washington Post, 12/15/17). It’s not hard to see how the sting of organized feminist retribution would inspire the surly enfant terrible to abandon a mission to afflict the comfortable and become the Joker.

Right-wing for other reasons

Naturally, Owned doesn’t tell the whole story. While Musk’s Twitter has become a right-wing vehicle (Atlantic, 5/23/23; Al Jazeera, 8/13/24; PBS, 8/13/24), a great many left and liberal writers and new outlets still find audiences on Substack. At the same time, many of the platform’s users threatened to boycott Substack (Fast Company, 12/14/23) after it was revealed how much Nazi content it promoted (Atlantic, 11/28/23). And while Substack and Rumble certainly harnessed Taibbi and Greenwald’s realignment, many other left journalists have gone right for other reasons.

Big Tech doesn’t explain why Max Blumenthal, the son of Clinton family consigliere Sidney Blumenthal, gave up his investigations of the extreme right (Democracy Now!, 9/4/09) for Covid denialism (World Socialist Web Site, 4/13/22) and a brief stint as an Assadist version of Jerry Seinfeld (Twitter, 4/16/23). Christian Parenti, a former Nation correspondent covering conflict and climate change (Grist, 7/29/11) and the son of Marxist scholar Michael Parenti, has made a similar transition (Grayzone, 3/31/22; Compact, 12/31/24), and he is notoriously offline.

Higgins’ book, nevertheless, is a cautionary tale of how reactionary tech lords are exploiting a dying media sector, where readers are hungry for content, and laid off writers are even hungrier for paid work. They are working tirelessly to remake a new media world under their auspices.

To remake the media environment

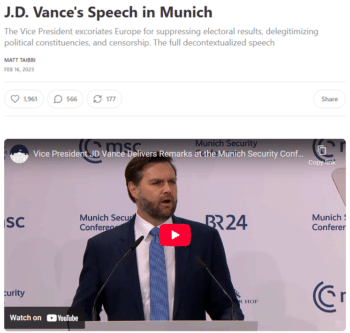

Taibbi, who once upon a time spoke at Occupy Wall Street, has lazily morphed into a puppet for oligarchic state power, using his Substack (2/16/25) to literally repost Vice President J.D. Vance’s speech in support of the European far right in, of all cities on earth, Munich.

Thiel, Andreessen and Musk have the upper hand. While X is performing poorly (Washington Post, 9/1/24) and Tesla is battered by Musk’s plummeting public reputation, Musk’s political capital has skyrocketed, to the point that media outlets are calling him a shadow president in the new Trump administration (MSNBC, 12/20/24; Al Jazeera, 12/22/24). Substack is boasting growth (Axios, 2/22/24), as is Rumble (Motley Fool, 8/13/24).

Meanwhile, 2024 was a brutal year for journalism layoffs (Politico, 2/1/24). It saw an increase in newspaper closings that “has left more than half of the nation’s 3,143 counties—or 55 million people—with just one or no local news sources where they live” (Axios, 10/24/24). A year before that, Gallup (10/19/23) found that

the 32% of Americans who say they trust the mass media “a great deal” or “a fair amount” to report the news in a full, fair and accurate way ties Gallup’s lowest historical reading, previously recorded in 2016.

The future of the Intercept, which Greenwald helped birth, remains in doubt (Daily Beast, 4/15/24), as several of its star journalists have left to start Drop Site News (Democracy Now!, 7/9/24), which is hosted on—you guessed it—Substack.

Rather than provide an opening for more democratic media, this space is red meat for predatory capital. The lesson we should draw from Higgins’ book is that unless we build up an alternative, democratic media to fill this void, an ideologically driven cohort of rich industrialists want to monopolize the communication space, manufacturing consent for an economic order that, surprise, puts them at the top. And if Taibbi and Greenwald can find fame and fortune pumping alt-right vitriol on these platforms, many others will line up to be like them.

What Higgins implies is that Andreessen and Thiel’s quest to remake the media environment as mainstream sources flounder isn’t necessarily turning self-publishing journalists into right-wingers, but that the system rewards commentary—the more incendiary the better—rather than local journalists doing on-the-ground, public-service reporting in Anytown USA, where it’s needed the most.

Greenwald and Taibbi’s stature in the world of journalism, on the other hand, is waning as they further dig themselves into the right-wing holes, and the years pass on from their days as scoop-seeking investigative reporters. Both ended their reputations as members of the Fourth Estate in favor of endearing themselves to MAGA government.

Taibbi has lazily morphed into a puppet for state power, using his Substack (2/16/25) space to literally rerun Vice President J.D. Vance’s speech in support of the European far right in, of all cities on earth, Munich. Greenwald cheered Trump and Musk’s destructive first month in power, saying the president should be “celebrated” (System Update, 2/22/25). Neither so-called “free speech” warrior seems much concerned about the enthusiastic censorship of the current administration (GLAAD, 1/21/25; Gizmodo, 2/5/25; American Library Association, 2/14/25; ABC News, 2/14/25, Poynter, 2/18/25; FIRE, 3/4/25; EFF, 3/5/25).

Past their sell-by date

And there’s a quality to Greenwald and Taibbi that limits their shelf life, a quality that even critics like Higgins have overlooked. As opposed to other left-to-right flipping contrarians of yore, the contemporary prose of Taibbi, Greenwald and their band of wannabes is simply too pedestrian to last beyond the authors’ lifetimes.

They value quantity over quality. There is no humor, narrative, love of language or worldly curiosity in their work. And they have few interests beyond this niche political genre.

Christopher Hitchens, who broke with the left to support the “War on Terror” (The Nation, 9/26/02), could write engagingly about literature, travel and religion. Village Voice civil libertarian Nat Hentoff, whose politics flew all over the spectrum, had a whole other career covering jazz. This made them not only digestible writers for readers who might disagree with them, but also extended their relevance in the literary profession.

By contrast, Taibbi’s attempts to write about the greatness of Thanksgiving (Substack, 11/25/21) and how much he liked the new Top Gun movie (Substack, 8/3/22) feel like perfunctory exercises in convincing readers that he’s a warm-blooded mammal. A Greenwaldian inquiry into art or music sounds as useful as sex advice from the pope. This tunnel vision increased their usefulness to the moguls of the right-wing media evolution—for a while.

Taibbi and Greenwald are not the true enemy of Owned; they are fun for journalists to criticize, but have slid off into the margins, as neither has published a meaningful investigation in years. The good news is that for every Greenwald or Taibbi, there’s a Tana Ganeva, Maximillian Alvarez, Talia Jane, George Joseph, Michelle Chen or A.C. Thompson in the trenches, doing real, necessary reporting.

What is truly more urgent is the fact that a dangerous media class is taking advantage of this media vacuum, at the expense of regular people.