This time last year, tens of thousands of people in Colorado anxiously wondered if they’d have to find a new doctor or start using a different hospital. Contracts setting payment levels for Catholic Church—affiliated hospital chain CommonSpirit Health to be a member of preferred provider networks run by insurer Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield of Colorado were set to expire on May 1, 2024, and negotiations were a train wreck.

The Summit (Colo.) Daily (5/2/24) amplified the anxiety health consumers felt in the face of providers’ and insurers’ threats.

CommonSpirit accused Anthem of trying to pay rates so low that its hospitals couldn’t afford to take care of patients, while Anthem shot back that CommonSpirit wanted rate increases at more than twice the rate of inflation (CBS KKTV 11, 4/30/24).

Media coverage reached a fever pitch as the deadline approached. Without a new agreement, Coloradans covered by Anthem insurance plans would have to pay far more out of pocket to use CommonSpirit hospitals and the system’s affiliated doctors (Denver Post, 4/26/24). The potential consequences would be extreme in communities where CommonSpirit is a dominant provider, especially in the state’s rural and resort areas, where the company’s facilities are the only available option for miles around (KOAA, 5/1/24). “What Do We Do?” a plaintive Summit Daily headline (5/2/24) asked.

The high-stakes negotiations dragged on for more than two weeks past the contract’s expiration, with the two corporate giants contending that the other side wanted dangerously low or unaffordably high rates.

The eventual settlement was greeted with a mixture of relief and anger from patients whose care had been disrupted. La Plata County resident Christie Hunter, whose son Ollie suffers from myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disorder that weakens voluntary muscles, told the Durango Herald (5/17/24, 5/1/24) she was glad the two healthcare titans had settled, but angry that the dispute disrupted her family’s healthcare. The time spent looking for new providers “would have been much better spent trying to help my son, and get him feeling well enough to go to school.” Ollie’s first day at school after months of treatment and preparation was the day the Hunters received initial notice that they could lose access to his specialists.

Although the high-stakes conflict was about money, the terms of the new five-year price deal remain secret.

Performative hostage-taking

This kind of performative patient hostage-taking has become standard practice in hospital rate negotiations across the U.S. At least four major network contracts in Ohio/Virginia, Connecticut, Texas and Missouri expired at the beginning of April alone.

Media coverage usually captures the anxiety that patients like the Hunters experience at the disruption of critical medical relationships. Otherwise, the quality and depth of coverage varies widely. Some reporting fuels public hysteria to the benefit of the parties, while the best coverage provides critical national context and alerts audiences what to expect.

To help FAIR readers understand what’s happening when these conflicts hit their communities, we’ve assembled a few lessons from the past few years, and principles that should frame local and regional media coverage.

Think mob war

These stories are best understood as economic warfare between gangsters dividing money already looted from the public. Insurers, who offer employers and patients nothing the government can’t do better and cheaper, fight with hospital corporations who wield monopoly power to negotiate the world’s highest prices for inpatient care, leaving millions of Americans saddled with unmanageable medical debt.

Communicating with the public and political leaders through the media is a key negotiating strategy for both hospitals and insurance companies. Each side accuses the other of threatening patients’ access to doctors and hospitals. The corporations issue a deluge of press releases, statements and FAQ webpages to inform patients of pending changes to coverage, and the consequences for their financial, physical and mental health—all seasoned with a heavy dose of spin. The goal is to ratchet up public anxiety as the deadline approaches, and attach blame to the other side to win concessions.

KFF Health News (2/1/19) accurately characterized the antagonists in the rate disputes as “behemoths.”

Negotiations receive intense local and regional media coverage, following the same script. Both sides publicize the looming deadline, and warn that patients may lose access to local hospitals and valued doctors. Insurers accuse hospitals of price-gouging, while hospitals insist that insurers want to pay them less than it costs to take care of patients.

You’ll probably keep your doctor

Outlets frequently catch on to the fact that they’re witnessing “a battle of Goliath and Goliath,” as Dallas-based D Magazine (4/1/25) framed a recent clash in Texas. But reporters and editors should also alert their audiences to the fact that the conflicts usually resolve themselves after a few weeks or months of widespread terror.

Large local and regional insurers can’t run provider networks without major hospital systems, and hospital systems can’t afford to lose access to patients covered by major health insurers. As Georgetown University professor Sabrina Corlette told KFF Health News (2/1/19) during a 2019 dispute in California:

When you have a big behemoth healthcare system and a big behemoth payer with tens of thousands of enrolled lives, the incentives to work something out privately become much stronger.

This is what the market looks like

The U.S. healthcare financing system relies on the mechanism of having private health insurance companies build networks that use financial and bureaucratic coercion to force patients to use hospitals and doctors within the network, instead of other providers. Insurers offer hospitals privileged access to the thousands of “lives” they cover in exchange for discounted rates. This is supposed to lower costs and improve the quality of healthcare.

You can’t have networks with discounted rates without rate negotiations, which is why these high-stakes gang wars are so common and will continue. The degree to which these rate negotiations are central to the functioning of “market-based” healthcare is a critical piece of context for reporters, too often missing from coverage.

In Colorado, for example, Pueblo Chieftain reporter Tracy Harmon largely followed the companies’ scripts in two stories (5/14/24, 5/20/24) on the Anthem/CommonSpirit fight, focusing on patients’ need for access and sourced almost exclusively to the two combatants.

Summit Daily News reporter Ryan Spencer (4/14/24) offered some additional context, using public data to show that the CommonSpirit hospital in Summit charged rates at twice the statewide average, and “reported profit margins of 35% or more in 2020 and 2021,” according to a report by the state Division of Insurance. Neither Spencer nor Harmon made the critical policy point that the network rate negotiations are supposed to be the country’s primary cost control mechanism.

It doesn’t work

In Colorado, Durango Herald reporter Reuben Schafir (3/23/24) came closest to discussing the core policy problem illustrated by corporate collisions over hospital rates. A spokesperson for a consumer healthcare NGO told Schafir:

These negotiations are often a lose/lose situation for consumers. Even a timely agreement would likely result in higher healthcare costs.

MIT economist Jonathan Gruber told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram (4/3/25) that insurer/provider conflicts illustrate why “the government should step in and regulate prices.”

In other words, the primary U.S. cost control mechanism doesn’t work. Leaving prices to the outcome of mob wars has given the U.S. the highest hospital prices in the world. Since hospital care remains the largest single element of national health spending, the failure of market-based hospital rate negotiations is one of the driving forces making the U.S. an outlier as the costliest system in existence.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram got this right. On April 1, contracts between Southwestern Health Resources (SWHR) and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas (BCBSTX) expired amidst the usual anxious media coverage (e.g., Dallas Morning News, 4/1/25; WFAA, 4/2/25; KDFW Fox 4, 4/1/25).

A long Q&A-style summary in the Star-Telegram (4/3/25; non-paywall MSN text here) featured MIT economist Jonathan Gruber saying that “really the insurers and the providers are both bad guys when it comes to costs.” According to Gruber, markets have failed, and

situations like these contract negotiations breaking down are good examples of why the government should step in and regulate prices that the private sector has failed to keep within reach of the average consumer.

Gruber’s quote could well have been national news itself. Gruber was the intellectual architect of the Affordable Care Act, and it’s remarkable for an expert of his stature and influence to say categorically that markets have failed, and that government needs to regulate prices. Regardless, Gruber’s observation that market contracts between private insurers and hospitals have failed, and are likely to continue failing, is essential to understanding what’s happening when the healthcare mob wars come to your town.

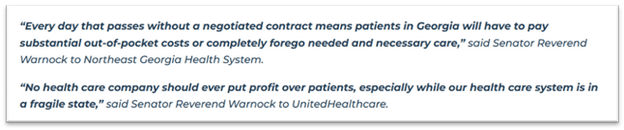

Washington gangsters agree

As usual in mob wars, politicians bought by the combatants publicly wring their hands, while collecting millions of dollars in campaign assistance from each side and doing nothing to end the carnage. When the allegedly charitable Northeast Georgia Health System and insurer UnitedHealthcare ramped up their fear campaigns in 2023, Sen. Raphael Warnock (D—Ga.) sent strongly worded letters to both parties, typically devoid of anything indicating whether and how Senator Warnock and colleagues intend to prevent this from happening again. The dispute was a rare one that ended without an agreement.

The ultimate missing context for these stories is that for all their public antagonism, the insurance and hospital industries march in lockstep on the most important policy questions in the nation’s capital. The American Hospital Association and health insurers both spend millions of the dollars they get from premiums, and the rates exchanged under the terms of these contracts, to defeat Medicare for All, and make even modest partial reforms, like Gruber’s proposed price regulation, politically impossible.

John Canham-Clyne is an independent investigative reporter based in New Haven, Connecticut. He recently returned to journalism after 26 years as a corporate researcher for the labor movement. He publishes the investigative newsletter Healing and Stealing.