With President Donald Trump and his team launching an aggressive attack on international institutions and threatening to pull out from many of them, there has been speculation about whether they would adopt the same strategy with respect to the Bretton Woods institutions. However, at the time of the April 2025 Spring meetings of the twins, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent made clear that U.S. policy with respect to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund would be different from that being adopted vis-a-vis UN bodies like the World Health Organisation (funding for which has been withdrawn) or the US’s own longtime soft power instrument the United States Agency for International Development (which for all practical purposes has been shut down).

Bessent emphasised that the U.S. wants the Bank and Fund to remain, but change their already “biased” policies by stepping “back from the expansive policy agendas”, including of course climate related projects, “that stifle their ability to deliver on their core missions”. The core missions are those which “contribute to making America safer, stronger, and more prosperous” by helping “the private sector thrive”.

Beneath that large agenda are some specific expectations. The IMF, for example, must stick to its “core functions of macroeconomic surveillance and lending to members facing balance of payments crises”, “put greater pressure on members to maintain fair and transparent currency practices” with a special reference to China’s “excess capacity”, its “unfair practices”, and the need to “provide a frank and even handed assessment of policies that hold back domestic demand and generate negative spillovers, harming workers and businesses in other countries”. It must also serve the interests of U.S. finance, by strengthening “implementation of its debt sustainability and transparency policies”, “preventing the buildup of unsustainable debt”, and forcing “recalcitrant bilateral creditors (read China) to come to the table to work with borrower countries”.

The World Bank too, he added, must “promote market-based economic growth and stability that will engender benefits for the world and the United States”, and promote “private sector-led, job-rich economic growth and market development”, which “will also help lay a solid foundation overseas that will attract U.S. exports and investment”.

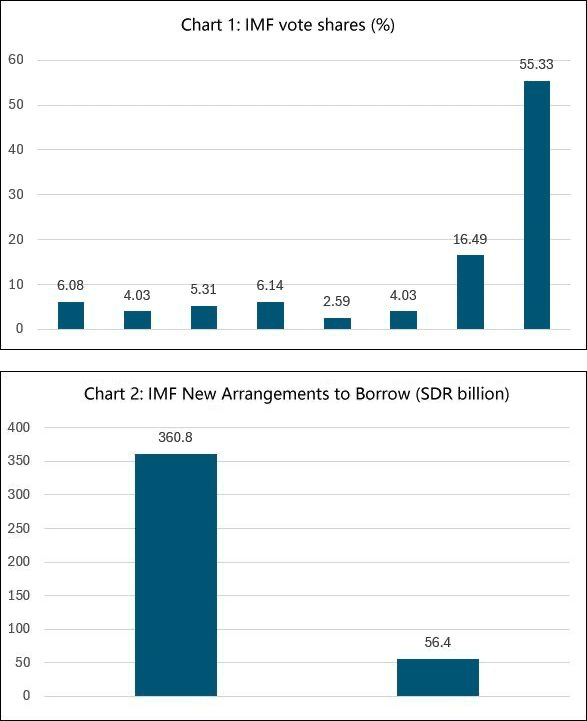

In sum, when it comes to the Bretton Woods twins, the U.S. wants them in place but with an emphasis on serving the interests of the declining hegemon. This is not surprising, since the U.S. has been able to exert huge influence on international economic affairs through these institutions for decades, in return for rather small sums of capital it has contributed to them. In the case of the IMF, the U.S. contributes SDR 83 billion for its quota share in the total of SDR 476.3 billion in return for a vote share of 16.5 per cent, which is way ahead of the 6.1 per cent each held by China and Japan, 5.3 per cent by Germany, 4 per cent each by France and the UK and just 2.6 per cent by Russia (Chart 1). Since all important decisions require at least 85 per cent of votes to go through, its larger than 15 per cent share allows the U.S. to veto any decision it does not like. In addition, European countries (with more than 20 per cent votes) have tended to vote with the U.S. on almost all matters. There have been repeated calls to significantly change the IMF’s voting structure to reflect the shifting economic strengths of different countries since the initial distribution of quotas. But despite the organisation being mandated to undertake quota reviews at least 16 times thus far, the U.S. has been able to use its voting strength to prevent dilution of its veto power. In return for that, the U.S. has agreed to commit SDR 56 billion of a total of SDR 361 billion to the IMF’s New Arrangements to Borrow (NAB) (Chart 2) or its so-called “second line of defence” in the form of funds it can access to fulfil its mandate when demands on its resources are high. But that is a commitment which has never been fully tested.

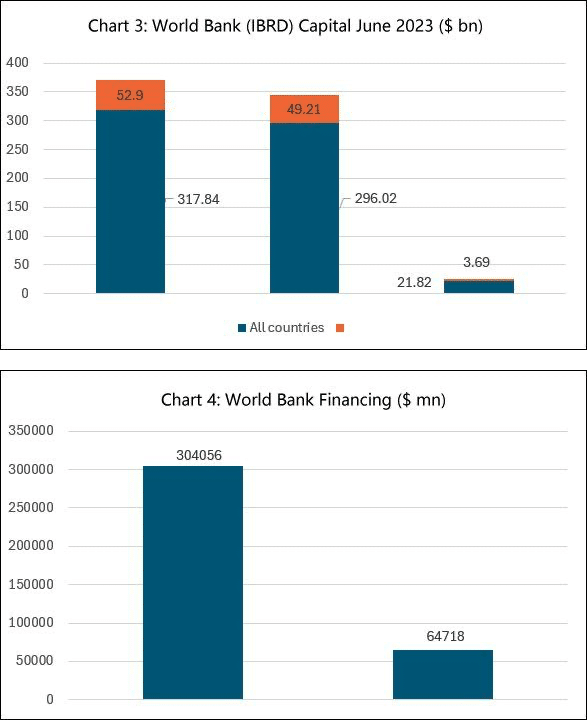

A similar situation holds with respect to the World Bank, where the U.S. outlays only $3.7 billion as its share of actual paid in capital totalling $21.8 billion. The rest of its commitment is in the form of $49.2 billion of a total of $296 billion of “callable capital” (Chart 3). Callable capital can only be requisitioned to meet bond and guarantee obligations, and can be so called only after efforts to meet any such obligation with the IBRD’s special reserve, surplus, and the income earned on its paid-in capital and retained earnings have failed. But the existence of that backstop gives the Bank the highest credit ratings in capital markets. As a result, in practice the Bank supports its lending operations by borrowing rather than shareholder contributions. Its borrowing at the end of 2024 stood at $304.1 billion, as compared with an equity base of $64.7 billion (Chart 4). Moreover, with the Bank never agreeing to take a haircut on any loans it provides, it is constantly accruing surpluses. The interest revenue earned on loans net of the cost of capital for the six months ended December 2024, for example, stood at a comfortable $2.5 billion.

Here again, with its small commitment of funds the U.S. is able to exercise veto power because it has managed to retain a 15.8 per cent vote share compared with 7.0 per cent held by Japan, 5.9 per cent by China, 4.2 per cent by Germany, 3.8 per cent each by France and the UK and just 2.8 per cent by Russia (Chart 5). With the dice loaded heavily in its favour, there is no reason why a U.S. administration trying to reassert power as a declining hegemon would walk away from these institutions. All it wants is for them to be even more crudely partisan than they have hitherto been.

This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 12, 2025.