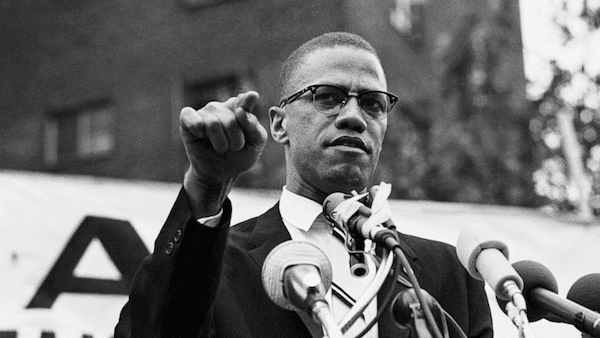

One hundred years after his birth, 60 years after his assassination, Malcolm X is synonymous globally with revolutions and all forms of militant struggle by exploited and oppressed people. Eulogized as “Our Shining Black Prince,” el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz was the avenging angel of Black America. Representing the righteous rage of the Black Nation, channeled through a disciplined eloquence, a living reminder of the chickens that may come home to roost in the coops of white supremacy at any time.

A self-taught working class intellectual, Malcolm X symbolized the possibilities for exploited and oppressed people to take their destiny into their own hands and master worlds denied to them purely due their class and race (or both). A master organizer, Malcolm brought together networks and built organizations, religious and secular, across the U.S., and forged significant ties between the Black Liberation Movement in the U.S. and national liberation movements around the world.

Malcolm X, simply put, was a revolutionary—one who ranks high in the pantheon of those who dared to struggle, and dared to win.

A nation personified

Malcolm X was the son of Garveyites, raised in the fold of the largest organization to ever exist among African-descended people in the Americas, the United Negro Improvement Association. Many of his earliest memories were from the UNIA meetings held in his home, and their slogans like: “Africa for Africans.” Malcolm’s father was murdered by the nexus of police officers and KKK-style vigilantes that terrorized militant Black organizations for his leadership in the UNIA.

Malcolm was a devotee of Paul Robeson, following everything about him in the newspapers and the radio while imprisoned. As author Karl Evanzz noted in his book, “ The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X”: “[Malcolm’s] letters to friends echoed Robeson’s arguments against apartheid and American interventionism.” The same author further notes that,

Anyone who has heard Robeson and Malcolm X speak will attest, an equal part of his speaking ability clearly derived from the close attention he had paid to Robeson’s delivery techniques.

It’s not surprising that the then-Malcolm Little would also be drawn to Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Like the UNIA, the NOI was a strong voice for Black humanity. And like Robeson, it was in solidarity with anti-colonial movements sweeping the globe. Further, the Nation’s proposal for a Black nation in the Deep South was reminiscent of the Black Belt Thesis, put forward by the Communist party and Black communist Harry Haywood, who would later say a study of the Garvey movement helped inspire his conception and advocacy of the thesis. Interestingly enough, Haywood’s book on the Black Belt Thesis, “Negro Liberation,” was funded by Robeson.

Malcolm X was a product of a rich soil of uncompromising Blackness. As a younger adult, he was drawn both politically and theologically to those looking to uplift the Black race and smash imperial domination of what is now called the “Global South.” By the 1960s, he would become the seminal figure in the U.S. representing those same themes.

Internationalist by nature

The Black Liberation Movement has always been internationalist, and Malcolm X spent significant time nurturing these trends. As the Harlem minister for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm engaged heavily with the African diplomatic community and representatives of national liberation movements, frequently inviting them to speak to Harlem audiences.

Famously he welcomed Kwame Nkrumah and Fidel Castro to Harlem, and he was known to meet leaders like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, Guinea’s Sekou Toure and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia when they attended United Nations meetings. He also met Patrice Lumumba during the latter’s 1960 visit to the United States. Ben Bella, the leader of the Algerian revolution was another who made sure Minister Malcolm was on his schedule.

After leaving the NOI, he redoubled his efforts to create alliances between Black liberation fighters and national liberation forces globally. He would tour the African continent, becoming immensely popular, and he also traveled to Gaza to meet with leaders from the Palestinian Liberation Organization.

Malcolm’s efforts to bring the Black Liberation Movement into working cooperation with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist forces terrified the government—so much so that in 1964, an assistant to the Secretary of State contacted the CIA unit that oversaw assassinations and “insisted” they penetrate Malcolm’s inner circle. The FBI, reputedly coordinating with President Lyndon B. Johnson himself, was working to do the same.

‘It is impossible for capitalism to survive’

Malcolm directly related the struggles of colonized peoples to be free to the destruction of capitalism:

It is impossible for capitalism to survive, primarily because the system of capitalism needs some blood to suck. Capitalism used to be like an eagle, but now it’s more like a vulture. It used to be strong enough to go and suck anybody’s blood whether they were strong or not. But now it has become more cowardly, like the vulture, and it can only suck the blood of the helpless. As the nations of the world free themselves, then capitalism has less victims, less to suck, and it becomes weaker and weaker. It’s only a matter of time in my opinion before it will collapse completely.

Not terribly long after, in response to a question at a public forum, he noted “You can’t have capitalism without racism.” This prompted a comment from another participant who stated the capitalist system was the true enemy of freedom, justice and equality, to which Malcolm responded:

And that is the most intelligent answer I’ve ever heard on that question.

Enduring legacy of struggle

Malcolm’s impact perhaps can be best understood by considering the constellations actively or hoping to engage with his organizing work. Leaders of the (then non-existent) Black Panthers, League of Revolutionary Black Workers and Republic of New Afrika were all followers of Malcolm X.

At the time of his death, Malcolm was engaging with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee speaking in Alabama to radical Black youth and hosting Fannie Lou Hamer in Harlem. He was slated to speak in Jackson, Mississippi at a SNCC organized event shortly after the date he was assassinated.

Not long before Malcolm’s death, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was actively reaching out to him, seeking to collaborate on Malcolm’s proposal to pursue action in the United Nations, in conjunction with African states, against the U.S. for its violations of the human rights of Black people. Malcolm was also increasingly engaging with socialist organizations whose multi-national memberships were playing their own part in the struggle against white supremacy.

Up until the last moments of his life, he was working to connect and organize with all the vital forces in the U.S. and around the world willing to seriously take on racism, colonialism, imperialism and capitalism—to build organizations, alliances and infrastructure to challenge such powerful forces and to use the appropriate tactics, at the appropriate times to actually win, by any means necessary.