Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

A horrifying statistic hovers over the poorer nations: 3.4 billion people now live in countries that spend more on interest payments for public debt than on education or health. In 2024, according to a new report from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global public debt reached $102 trillion—a third of which is held by developing countries. The impact on these countries is especially severe: credit markets charge poorer nations far higher interest rates than they do richer nations, making debt servicing payments proportionately higher for the Global South. The United States, for instance, pays interest rates that are, on average, two to four times lower than those faced by poorer nations.

In 2023, according to the UNCTAD analysis, the poorer nations ‘paid $25 billion more to their external creditors in debt servicing than they received in fresh disbursements, resulting in a negative net resource transfer’. In more popular language: the social wealth of developing countries is being drained by wealthy creditors—mostly located in the Global North.

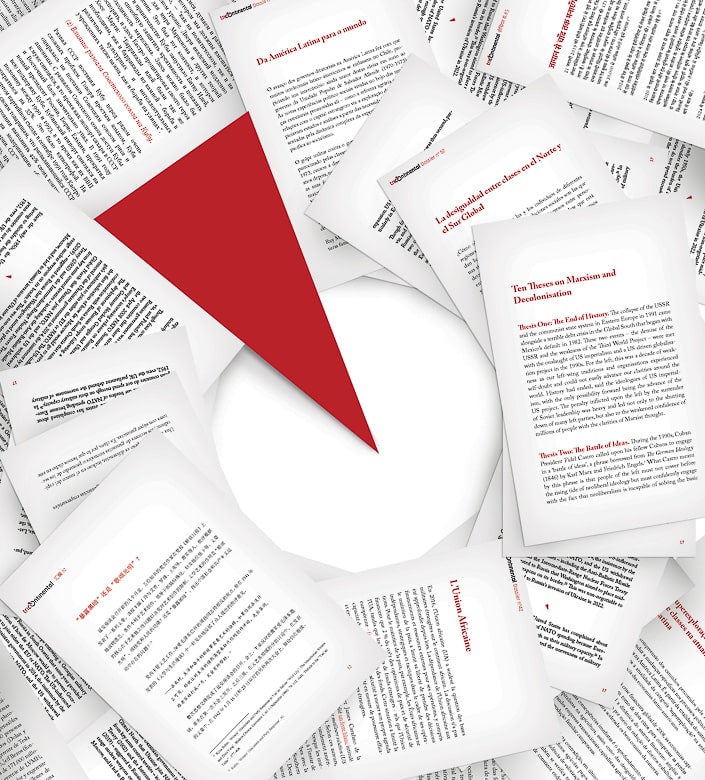

The theft of social wealth from South to North has framed the work of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research for the past decade. Following the Second Dilemmas of Humanity Conference (held in Brazil in 2015), our institute was founded to provide intellectual support to political and social movements and accompany them in the fight for emancipation. In the years since, our work has focused on four key areas:

- Highlighting the work of movements, as in our 2024 dossier The Political Organisation of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST).

- Elaborating critiques of the current system from the standpoint of the movements themselves, as in our 2023 notebook The World in Economic Depression: A Marxist Analysis of Crisis, which examines the continuing fallout of the Third Great Depression triggered by the U.S. mortgage crisis in 2008.

- Building an alternative framework for development that goes beyond the IMF’s debt-austerity regime, as introduced in our 2025 dossier Towards a New Development Theory for the Global South.

- Providing clear, accessible analysis of global developments and political struggles through our newsletters—published from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe—which aim to stimulate debate, sharpen political clarity, and strengthen internationalist consciousness.

To mark our ten-year anniversary, we produced dossier no. 90, How the World Looks from Tricontinental (July 2025), which presents our general view of the current conjuncture. Our assessment builds on five main arguments:

- Globalisation and neoliberalism enabled the capitalist class in the Global North to withdraw from productive investment in their own countries, leading to stagnation and austerity. This dynamic was cemented with the onset of the Third Great Depression.

- The realisation that the Global North would no longer be the buyer of last resort led many of the larger Global South countries to revive the idea of South-South cooperation for trade and development, culminating in the creation of the BRICS group in 2009, which has since expanded to BRICS+.

- The global economic centre of gravity has shifted from the North Atlantic to East and Southeast Asia, where the main centres of manufacturing and technological innovation are now located.

- The Global North faces growing difficulties in asserting political control over the international system due to its relative economic decline, even as it continues to dominate militarily and in communications infrastructure.

- Rather than compete economically with the rising Asian economies (led by China), the Global North, led by the United States, is pushing a New Cold War against China, using military and economic pressure to contain its technological and industrial advances.

Our latest dossier concludes with a short note on the state of the class struggle amid these changes:

More and more of the world is in motion, seeking to break from neoliberalism and imperialism and assert sovereign rule and paths of development. More and more people across the world seem to understand the futility of permanent austerity. But their projects are fragile and appear in ways that are not necessarily progressive. As of yet, the quantity of areas that seek to break from the current world order is not widespread or powerful enough to change the quality of the world order. But change is on the horizon. It is at the heart of the global class struggle. Something is bound to happen.

The question of quantity and quality is key here. There are a vast number of protests erupting across the world, and there are sections of the world whose governments have the political will to break with the neocolonial order. However, the world system—still dominated by the U.S.-led bloc—has not yet been fundamentally altered by this wave of rebellion.

In the early 2010s, a wave of protests against the IMF-imposed debt-austerity regime swept across the Global South. At the time, it appeared as if no solution to the misery was possible. The protests themselves came to define the post-Great Depression era. But then, a shift began to take place: the emergence of a more confident South—what we call the ‘New Mood’ in the Global South. This new mood is not generated by the mass struggles of the working class and the peasantry but by increased assertions for political and economic sovereignty of Global South governments. The formation of BRICS was one signal of this new mood; another is the growing insistence on a new development theory and the building of alternative institutions that serve the interests of the Global South, such as the New Development Bank, established in 2014 by the BRICS countries.

These moves have begun to shift us from a period of protest to one of construction. Can the poorer nations build a new architecture for development and sovereignty? Can this new architecture supplant the old? These are the questions of our time.

As part of our contribution to this new architecture, I am pleased to announce that Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research has a new chief economist, Emiliano López, whose work on the Dependency Index and on the geopolitics of inequality has been groundbreaking. He will lead our team in shaping our contribution to the new development theory.

There is no way to accurately predict whether the IMF approach will prevail or whether a new development theory—with a new development architecture—will establish itself.

Warmly,

Vijay