Last week, the mega tech companies—the so-called Magnificent Seven—presented their latest earnings results. They appeared to be ‘blockbuster’. They painted a picture of a booming economy, supporting President Trump’s assertion that America “is the hottest country anywhere in the world”. (He was not referring to global warming). At the same time, Trump announced his latest round of tariff measures on goods exports from other countries into the U.S. The U.S. stock market continued to stay near a record high.

The financial media lauded the tech results and even went along with the Trump administration’s claims that all the fears about the hit to U.S. economic growth and inflation from Trump’s tariff measures had been proved wrong.

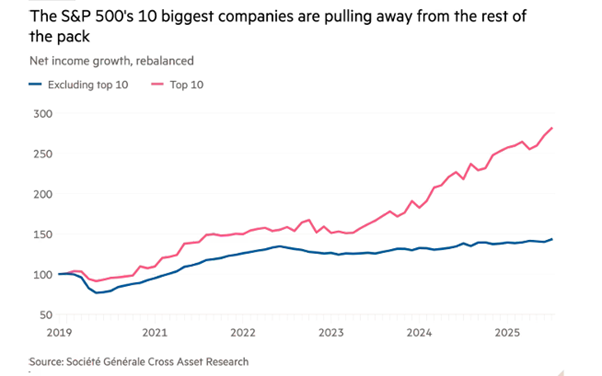

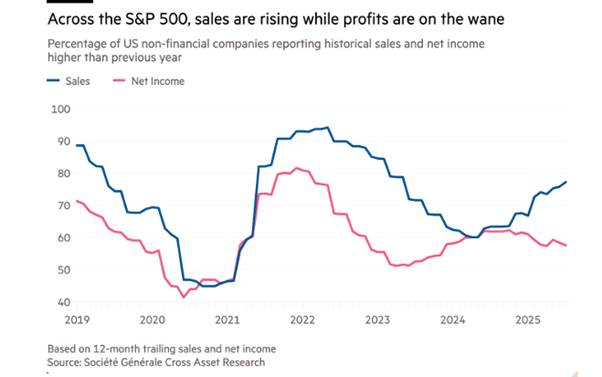

But the more you look at the data below the stock market hype and Trump’s claims, the reality is much less rosy. Below the surface, large parts of corporate America are grappling with slowing profits and the uncertainty generated by Trump’s aggressive trade war. With almost two-thirds of S&P 500 companies having reported second-quarter results, earnings for consumer staples and materials companies are down 0.1 per cent and 5 per cent year on year, according to FactSet data. Indeed, 52 per cent of those S&P 500 companies to have posted results, have reported declining profit margins, according to Société Générale.

The 10 biggest stocks on the S&P 500 account for one-third of overall profits across the index, with tech and financials reporting year-on-year quarterly earnings growth of 41 per cent and 12.8 per cent, respectively.

And when we delve into the earnings results of the Magnificent Seven, we find, contrary to the views of the financial media, that their earnings rises are not due to revenues and profits accrued from the huge investments in AI made by these companies, but from existing services created from the previous tech boom in the internet and social media. Meta’s (Facebook) shares jumped more than 11 per cent on their results adding more than $150bn to its market value. But the rise in earnings came from increased advertising revenues in existing services, not AI.

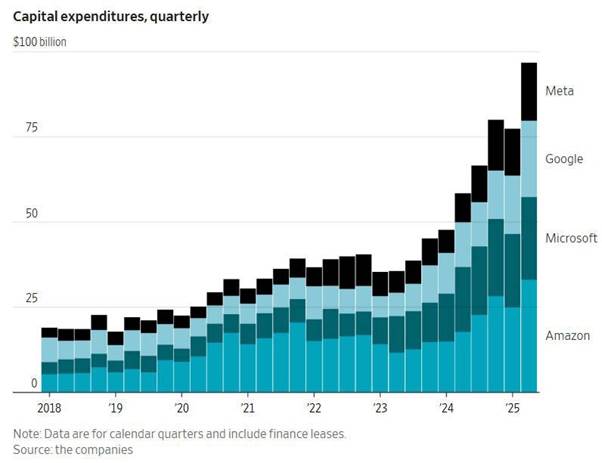

Meta’s Zuckerberg proclaimed that he is investing ever more in AI data centers and energy sources. “We are making all these investments because we have conviction that superintelligence is going to improve every aspect of what we do from a business perspective,” Zuckerberg said on a call with investors. However, Meta’s finance officer Susan Li said Meta was not anticipating “meaningful” revenue from its generative AI push this year or in 2026. And the company cautioned that the costs of building the infrastructure needed to underpin its AI ambitions were growing. Meta raised the lower end of its 2025 capital expenditures forecast to between $66bn and $72bn. It said that it expected its 2026 year-over-year expense growth to be higher than its 2025 growth rate, citing higher infrastructure costs and growth in employee compensation due to its AI efforts.

Over at Microsoft, quarterly profits soared from record revenues in its cloud computing division. But it too is looking to make future money from its massive investment in artificial intelligence. Finance officer Amy Hood said Microsoft spending on data centres would rise to $120bn in 2026 up from $88.2bn in 2025 and almost quadruple the $32bn in 2023. “We are going through a generational tech shift with AI . . . We lead the AI infrastructure wave and took share every quarter this year, we continue to scale our own data centre capacity faster than any other competitor.” But little or no revenue comes from AI so far. Copilot AI apps now had 100mn monthly users, Google’s Gemini with 450mn users and market leader ChatGPT, with more than 600mn. But only 3% actually pay for AI.

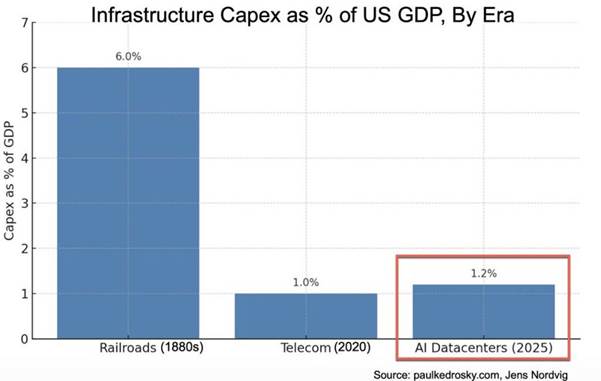

Already Microsoft and Meta capital expenditure is more than a third of their total sales. Indeed, capex spending for AI contributed more to growth in the U.S. economy in the past two quarters than all of consumer spending.

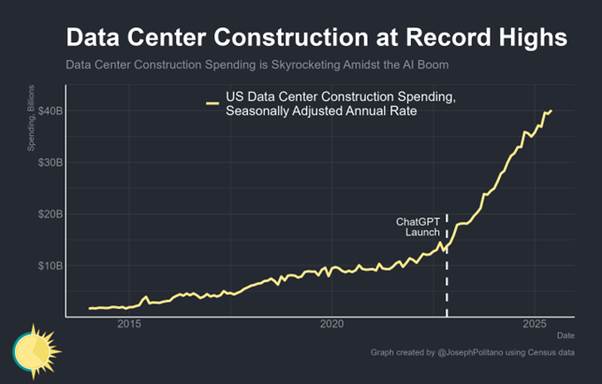

And there is no end yet to the AI investment boom. U.S. data center construction hit another record high in June, exceeding $40bn annualized for the first time. That’s up 28% from this time last year and up 190% since the launch of ChatGPT nearly three years ago.

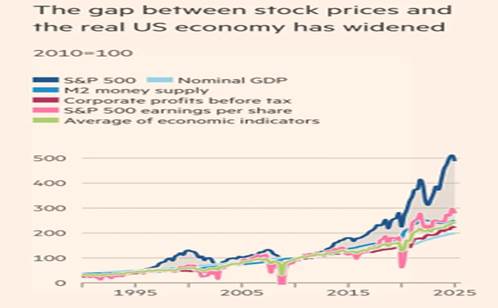

But this boom in the stock market, driven by AI hype, is increasingly out of line with the rest of the U.S. economy.

Take the latest U.S. real GDP figures. After the data showed that the Eurozone grew only 0.1% in Q2 2025, the U.S. data showed a rise in real GDP of 0.7%, which translated into an annualised rate of 3.0%, more than forecast. Trump hailed the result. But the headline growth rate was mainly due to a sharp fall in imports of goods into the U.S. (-30%) as the tariff rises began to bite. The fall in imports meant that net trade (that’s exports minus imports) rose sharply, adding to GDP. Excluding trade and the impact of the tariffs, real final sales to private domestic purchasers, the sum of domestic consumer spending and gross private fixed investment, slowed to a rise of just 1.2% compared to 1.9% in Q1.

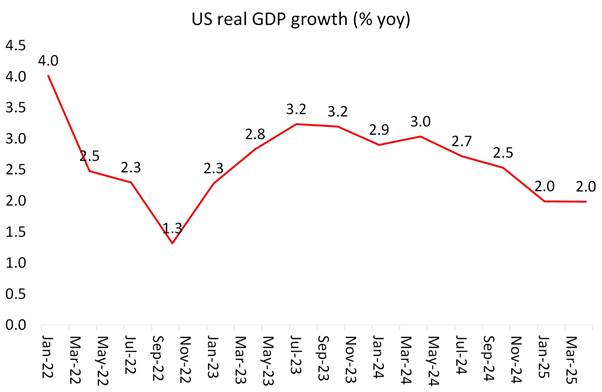

Indeed, investment growth dropped back in Q2, up only 0.4% vs 7.6% in Q1. Investment in equipment grew only 4.8% compared to the huge 23.7% rise in Q1, while investment in new structures (factories, data centres and offices) fell 10.3% in Q2, having also fallen 2.4% in Q1. Looking through all these volatile changes, the overall picture is that the U.S. economy rose 2.0% in real terms in Q2 2025 over the same period in 2024, at the same rate as in Q1. The U.S. economy is still doing better than the Eurozone and Japan, but at less than half the rate of China.

Source: BEA

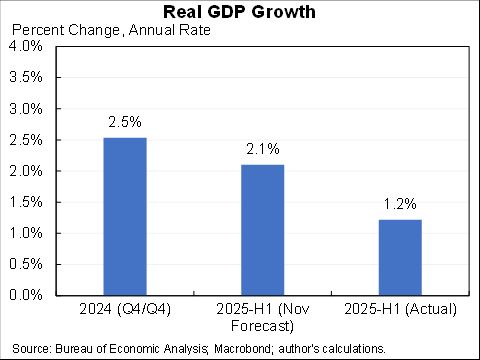

Mainstream economist Jason Furman points out that U.S. real GDP growth for the first half of 2025 averaged just a 1.2% annual rate, well below the pace in 2024. So the current 2% a year rate as above is likely to slip further.

Source: Jason Furman

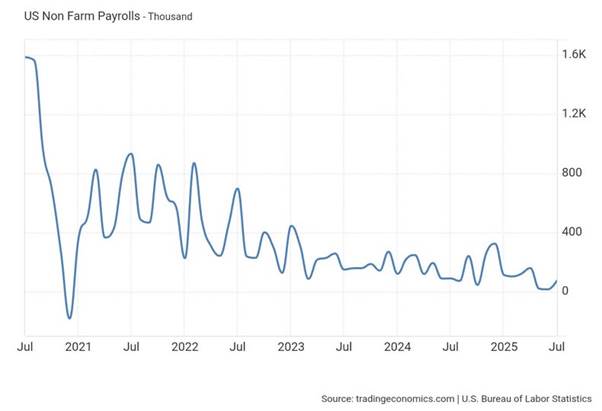

And then there is employment. The latest release on jobs growth in the U.S. was ugly. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics said there was only a tiny 73k increase in July and previous May and June data were revised down sharply, while the unemployment rate rose. Indeed, only 106,000 jobs have been added from May to July, down sharply from the 380,000 added in the previous three months.

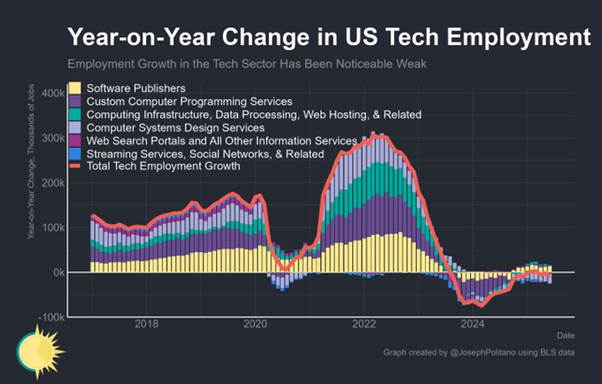

This is now the worst job market in the U.S. since the end of pandemic slump. Layoffs are at their highest level with nearly 750k job cuts in H1 2025. Even the high flying tech sector has seen a loss of jobs. Across all subsectors, jobs growth remains well below the peak tech era of 2022 or even the pre-COVID era.

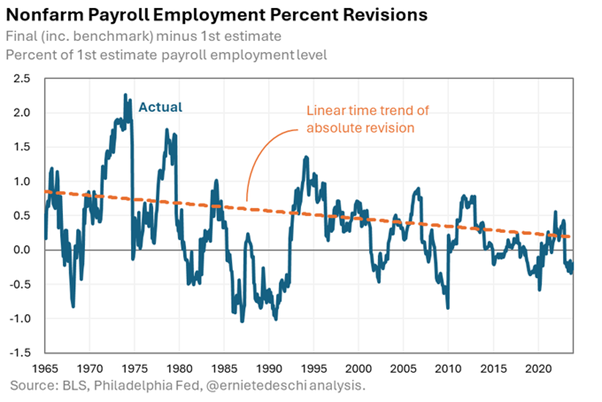

Blame the messenger. On the news of July jobs figures, Trump claimed the U.S. economy had never been stronger; the figures had been rigged and so he sacked the longstanding head of Bureau of Labor stats. It’s true that the jobs statistics are volatile and the Bureau finds it difficult to reconcile different measures of employment growth, but the irony in Trump’s move is that the Bureau’s estimates of payroll employment have got more, not less, accurate over time.

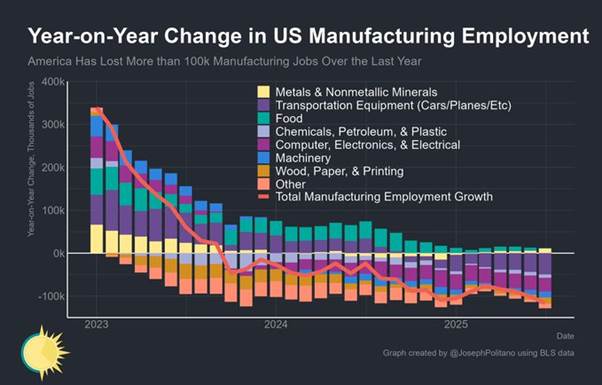

The reality is that the U.S. economy has been slowing down for some time and with it, employment growth. Indeed, America has lost 116k manufacturing jobs over the last year—that’s the fastest pace of job loss since the early COVID era and worse than any period from 2011-2019. Big drops in the transportation (-49k) & electronics (-32k) industries have driven most of the decline.

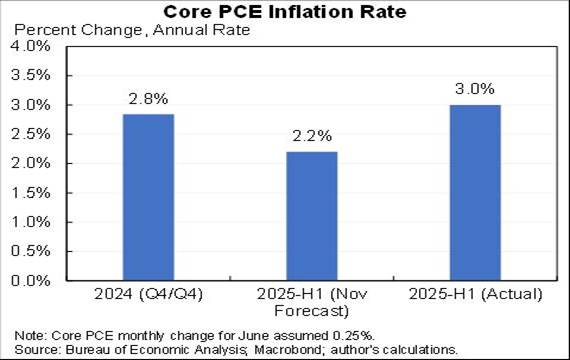

And then there is inflation. Far from inflation rates heading down as the economy slows, the official rates are staying stubbornly closer to 3% a year, instead of the target rate set by the U.S. Federal Reserve of 2% a year.

Source: Furman

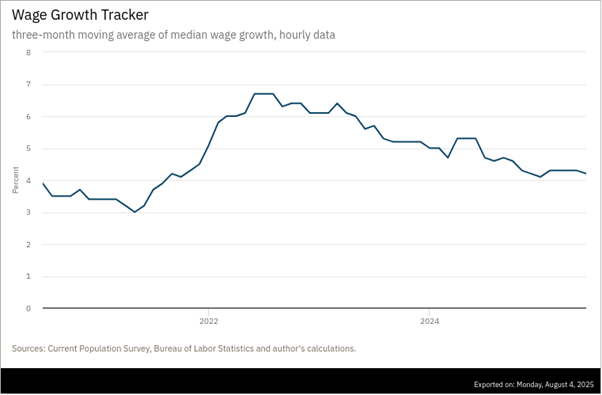

You might say, what difference does one percentage point make? But remember American consumers have suffered an average 20% rise in prices since the end of the pandemic slump and with average wage growth now slowing towards 3% a year, any real gains in living standards have disappeared.

Source: Atlanta Fed

Average real weekly earnings for full-time employees are now at the same level as just before pandemic, some five years ago.

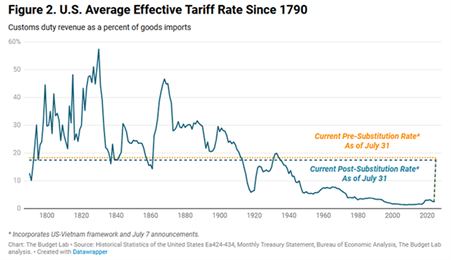

All this is well before Trump’s tariffs begin to hit the U.S. economy and consumers. As Fed chair Jay Powell put it: “American businesses have been absorbing Trump’s tariffs so far, but eventually the burden will be shifted on to American consumers.” Trump’s latest tariff measures are a mess with no rhyme or reason. He has raised high tariffs on some countries and in some sectors, but not in others. Since Trump took office, the average effective U.S. tariff rate on all goods from overseas has now soared to its highest level in almost a century: 18.2%, according to the Budget Lab at Yale.

Source: The Budget Lab

Trump says increased import tariffs are bringing in billions in extra revenue for a government that is running a huge budget deficit of about 6% of GDP a year. But the extra billions are tiny compared to the deficit and revenue is being lost from Trump’s cuts to corporate profits taxes and above all from the slowdown in the economy. Meanwhile, the U.S. trade deficit is running about 50 per cent above last year and will end up higher for 2025 as a whole, while GDP growth will be weaker.

Tariffs are typically paid by the importer of the product affected. If the tariff on that product suddenly goes from 0% to 15%, the importer will try to pass it on. So far, many have resisted and tried to absorb the extra cost. Some 50% say they are “absorbing cost increases internally.” But eventually, the tariff rises will feed into consumer prices. The Budget Lab at Yale estimates the short-term impact of Trump’s tariffs will be a 1.8% rise in U.S. prices, equivalent to an average income loss of $2,400 per U.S. household.

But the tariffs will also lead to less investment at home as U.S. manufacturers find the costs of importing components from abroad rising significantly, and domestic substitutes (if they exist) will be pricier. Profit margins will be squeezed even if prices are raised to compensate. That will add to downward pressure on U.S. economic growth. The Yale Budget Lab reckons if they stay as they are now, Trump’s tariffs will reduce GDP growth by 0.6% pts through the rest of this year and next year (that means the current growth rate of under 2% could fall below 1% by end 2026). As I have argued before, the U.S. economy would then enter a period of stagflation, where economic growth stutters to a near halt, while unemployment rises along with inflation.

This puts the U.S. Federal Reserve in a serious dilemma. Last week, the Fed’s monetary policy committee decided not to lower its policy interest rate. The Fed’s policy rate, which sets the floor for all borrowing rates in the U.S. and often globally, was held at 4.25% for the fifth straight meeting. This was despite threatening noises from President Donald Trump who wants a huge cut and says he will remove Fed Chair Powell if he does not get it. But if the Fed cuts rates, that will weaken its ability (such as it is) to control inflation and meet the 2% target. On the other hand, if it continues to hold rates up, then it will add to the borrowing costs of companies and households and so force further cuts in investment and employment.

Now I have argued in the past that Fed monetary policy has little effect on the economy: what matters are profits and their effect on investment. But the Fed’s dilemma between rising inflation and rising unemployment sums up the growing stagflationary environment in the U.S. And the impact of Trump’s trade tariffs has yet to be fully felt. So the Fed faces the prospect of a stagflationary economy.

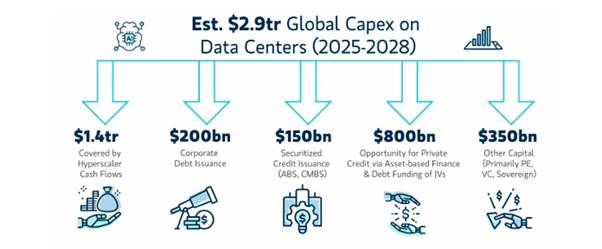

Meanwhile the AI capacity spending boom accelerates. The Magnificent Seven of mega tech companies are paying for this by running down their cash reserves and borrowing more. Of the planned investment in AI data centers of near $3trn by 2028, half will have come from using up cash flows and increasingly nearly another third from what is called ‘private credit’.

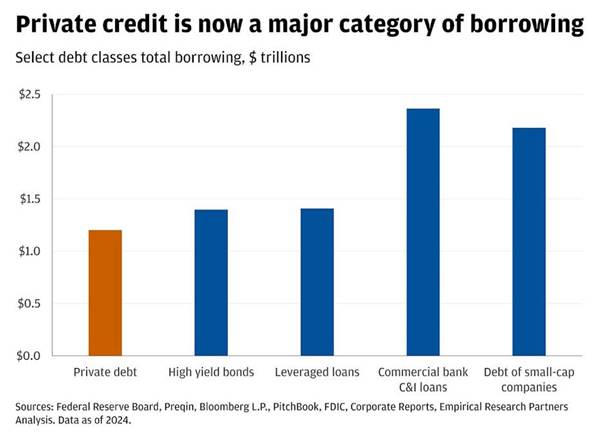

The tech companies are borrowing less in the traditional form of corporate bond issuance or bank loans and instead opting for getting credit from private credit companies that raise money from hedge funds, pension funds and other institutions and then lend it on. These credit vehicles are not regulated like the bond markets or the banks. So if things go wrong in the AI bubble, there could a rapid reaction in credit markets.

The U.S. has a record high stock market, unlimited spending on AI capacity by the tech giants, along with sharply increased borrowing to pay for it; but no sign yet of any significant revenues or profits from AI—and alongside that: a slowing rest of the economy, a widening trade deficit in goods and increasing unemployment and prices. All this as we go into the second half of 2025.