Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental Asia.

On 31 July 2025, U.S. President Trump announced a blanket 25% tariff on all exports from India to the United States. This came despite the conclusion of five rounds of bilateral trade negotiations, with the sixth round scheduled for later in August. Trump’s frustration was evident, as India continued to resist U.S. demands— particularly the opening of its agricultural sector to U.S. exports, especially dairy products.

In a series of outbursts on Truth Social, Trump denounced India’s trade barriers as ‘obnoxious’, referred to the country as the ‘tariff king’, and, in one of his more extreme remarks, described India’s economy as ‘dead’. He also threatened additional, unspecified penalties beyond the already announced 25% tariff, citing India’s continued purchase of Russian crude oil that was facing U.S. economic sanctions. That threat materialised on 6 August, when the Trump administration announced an additional 25% tariff on Indian exports. Once in effect, Indian exports to the U.S. will face a steep 50% tariff.

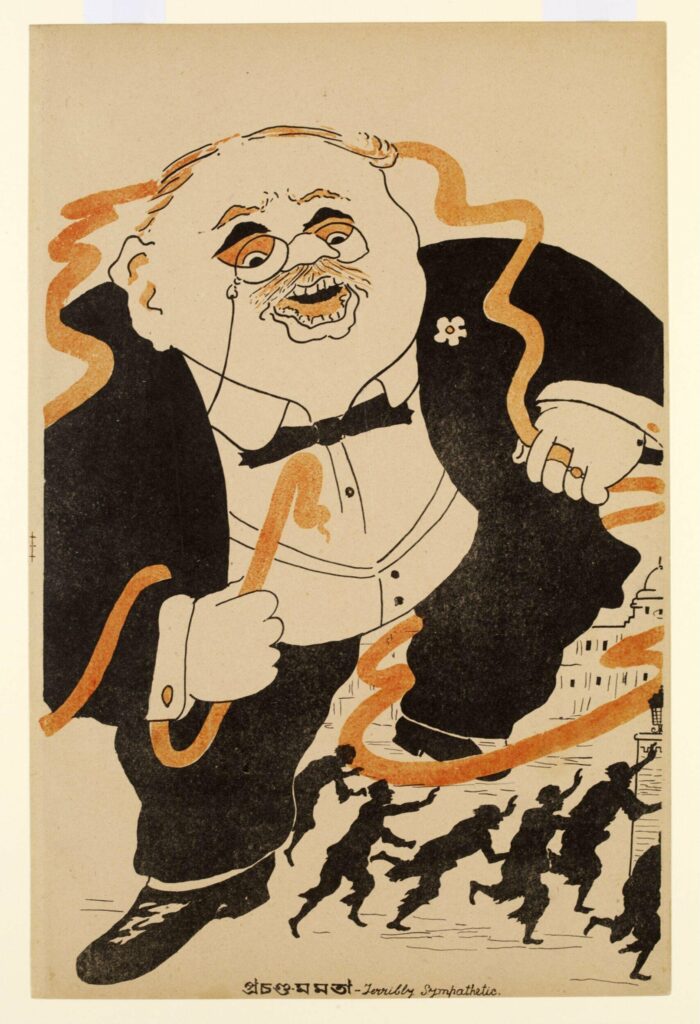

Gaganendranath Tagore (India), Terribly Sympathetic, 1917.

Trump’s outbursts and use of tariffs to arm-twist other countries into trade deals is now an internationally well-known tactic. Countries that rushed to conclude agreements in response to Trumpian threats have ended up with highly unfavourable terms. A case in point is the European Union, which accepted a lopsided deal. It now faces a 15% tariff on its exports to the U.S., while agreeing to invest $600 billion in the U.S. economy and purchase $750 billion worth of U.S. energy over three years. Meanwhile, U.S. exports to the EU will be duty-free. In Asia too, countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia have concluded trade deals with the U.S., which are likely to hurt them in the long run.

Trump’s intemperate language targeting India and the steep tariff imposed, is undoubtedly embarrassing for the Indian government and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, especially given his claims of a personal rapport with Trump, marked by periodic displays of obsequious bonhomie with his fellow right-wing demagogue. In this context, the Indian government’s refusal so far to yield to U.S. pressure is significant, and one hopes this position will hold in the coming months. It is hard not to recall the previous Trump administration, when India initially resisted U.S. demands to comply with sanctions on Iran and halt its oil purchases. In that case, the Modi government ultimately capitulated, ending all imports of Iranian oil and hurting its ties with a historically close neighbour, one that is critical not only to India’s energy security but also to its efforts to develop alternative trade routes linking it to Central Asia, Russia, and Europe.

The penal tariffs imposed on India appear to stem from two reasons: first, India’s refusal to open its agricultural market to tariff-free U.S. imports; and second, its continued purchase of Russian oil, citing its economic needs and energy security.

One of the key reasons for India resisting Uncle Sam’s pressure is that dismantling tariff protections for the agricultural sector would amount to political suicide of the ruling party. Over 45% of India’s population remains directly dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods. When the balance of payments crisis triggered India’s neoliberal turn in 1990—91, protections for agriculture were among the first to be dismantled. Between 1990 and 1996, average tariffs on agricultural imports fell sharply from 81% to 40%, exposing millions of Indian farmers to the volatility of international agricultural markets dominated by large agribusinesses and commodity speculators.

This led to a prolonged agrarian crisis, lasting more than a decade, marked by widespread farmer suicides due to debt. Unstable global prices of agricultural produces devastated rural incomes. It was also a period of serious political unrest, with frequent farmer protests across the country. The Indian political establishment would be careful not to recreate such a situation, considering Modi’s bitter experience with Farmers’ Protest in 2020.

Soon after Modi triumphantly returned to power for a second term in 2019, he took on the farmers enacting three farm laws. These laws would have facilitated the removal of price support to farmers, and put agricultural trade in the hands of private corporations. The strength of the resilient farmers, who poured into the national capital in protest, stationing themselves on the borders of the Delhi and forcing Modi, a first in his career as prime minster, to accept defeat and withdraw the three farm laws, is fresh in the mind of the current political dispensation.

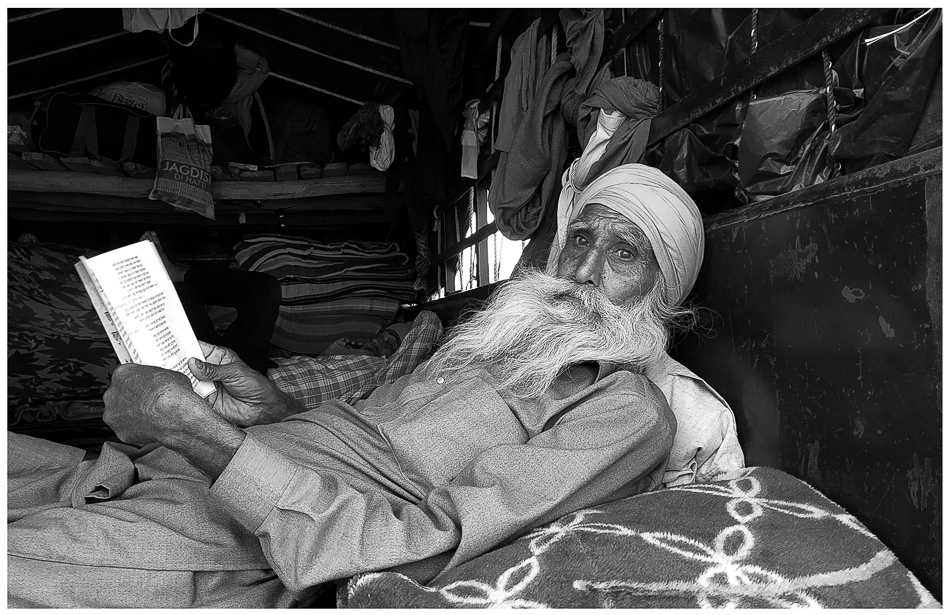

A farmer who joined in the initial protest reads work by the revolutionary Punjabi poet, Pash, in his trolly at the Singhu border in Delhi, 10 December 2021. (Photo: Vikas Thakur / Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

At the current conjuncture, when employment as well as investment in the manufacturing sector is stagnant and the shift away from agriculture to urban employment that took place till 2014, now somewhat reversed with people moving back to agriculture. Hurting the agriculture sector by removing tariffs and consequently causing damage to the rural economy is going to have severe consequences not only for the peasantry, but also for India’s overall growth .

The trade negotiations have not been open to public input or scrutiny. However, based on media leaks, one of the major sticking points appears to be U.S. pressure on India to open its dairy sector. India’s dairy economy is deeply embedded in peasant agriculture. Unlike the large-scale dairy farms in the U.S. that keep hundreds of cattle, Indian peasants typically keep only a few animals alongside crop cultivation.

Cattle rearing in India plays a crucial role in peasant economy. Given the seasonal variation in labour needs for crop cultivation, caring for cattle absorbs otherwise unutilised family labour. Crop residues, such as paddy and wheat straw, sugarcane and maize leaves, oil cakes, and farm weeds, are used as cattle feed, reducing the need for purchased inputs. For small-scale farmers, cattle rearing and milk sales are essential to make farming viable.

Over several decades, the Indian government has implemented policies to increase milk yields and improve availability, beginning with Operation Flood in the 1970s. As a result, India has become self-sufficient in milk production and dairy consumption has steadily risen—making a significant contribution to improving protein intake among the country’s undernourished population.

Succumbing to Trump’s demands for tariff removal on dairy products would be a severe blow to India’s dairy sector, reversing decades of effort to build self-sufficiency. The country’s long-term nutritional security would be placed at the mercy of international markets and U.S. whims, dragging India back to the 1960s when its leadership had to approach the United States with a begging bowl for wheat to feed its population.

Arunkumar H G (India),

Bhu-ka (Diet of the Earth), n.d.

Clearly this is an outcome the Indian state would be wary of—irrespective of which party is in government. As such, the Indian government may never agree to U.S. demands on agriculture. Moreover, India’s leadership and commentariat appear to believe that the steep tariff imposed by the U.S. is a temporary measure, likely to be reversed once a trade deal is concluded on more favourable terms.

Having fallen behind East Asia in comprehensive industrialisation and technological development, Indian policymakers hope to gain ground by replicating China’s success of export-oriented growth driven by access to Western markets, with the U.S being the major one.

Since President Trump’s first term, when the U.S.-China trade conflict moved to the centre of global economic tensions, Indian businesses and the government have anticipated an opportunity to fill the potential vacuum in global supply chains serving Western consumers. As the U.S. pushes for a decoupling from Chinese production, taking advantage of the so-called ‘China+1’ strategy of U.S. companies, India hopes to leverage its massive labour force to attract a large share of this redirected investment and export demand.

Apart from the size of its labour force to attract investments that are looking to diversify production away from China, India’s calculations for export-oriented growth also hinge on the anticipation that the U.S. would look at India as a strategic counterweight to China. India-China border tensions, marked by unresolved border issues, have fostered this outlook. It is also true that U.S. would like to co-opt India into various geopolitical schemes to contain China—one example being India’s membership in Quad. India has also for the last two decades increasingly shown willingness for a closer strategic embrace of the United States.

Aswath (Young Socialist Artists, India), Marching with the Peasants, 2021.

While India is unlikely to agree to removing tariffs on U.S. agricultural imports, it may well yield to U.S. pressure and step back from Russian oil purchases, as it did earlier in the cases of Iran and Venezuela. It may also allow itself to be dragged in to support U.S. geopolitical agendas in Asia.

This strategy is, of course, deeply dangerous. India risks being dragged willy nilly into conflicts initiated by the U.S. in Asia. Pakistan offers a cautionary example. Despite being a close strategic partner of the U.S. for over half a century, it remains mired in chronic economic distress and dependency. Even those countries that have secured impressive economic performance by aligning closely with the U.S.—such as Japan, South Korea, and its European allies—have increasingly become exemplary Henry Kissinger’s statement that ‘Being [United States of] America’s enemy is dangerous, but being its friend can be fatal’. The U.S.-engineered destruction of Ukraine, in its bid to contain Russia, stands as a sobering warning for India.

Even if Indian policymakers’ optimistic scenario materialises, and India secures a bilateral trade deal without hurting agriculture or compromising strategic autonomy—India is poorly placed to benefit from it. Past free trade agreements (FTAs), signed with great fanfare by India, have mostly led to widening trade deficits and further erosion of domestic industry. India’s FTA with ASEAN is a case in point, with the country’s trade deficit with ASEAN countries ballooning since its signing. Similarly, the recently concluded bilateral trade treaty with the UK is also unlikely to deliver significant gains, and is instead expected to hurt the pharmaceutical sector. India has reportedly diluted its position on compulsory licensing and patents, setting a precedent that could undermine its stance in future trade negotiations with other developed countries.

Warmly,

Bodapati Srujana, Tricontinental Asia

Bodapati Srujana is an Indian economist. Her work focuses on agrarian relations, banking and inequality.