The Eclipse of Art: Tackling the Crisis in Art Today

by Julian Spalding (New York: Prestel, 2003)

Scoffing at tradition is nothing new; neither is shocking the public. To skewer the bourgeois (without gutting him entirely, and thereby losing his patronage) is something every artist must do, if only to prove his revolutionary bona fides. Sometimes the skewer amuses: as when a French critic exhibited a blank sheet of paper said to represent anaemic girls at their first communion in a snowstorm — this done in 1883, when Bouguereau was painting rosy-cheeked putti and Meissonier was peopling his canvases with images of Napoleon’s Grande Armee. Sometimes the skewer outrages: as when Duchamp brought his infamous urinal to the Society of Independent Artists Exhibition in 1917. A masterwork in porcelain: what could you say to that?

After Duchamp’s pissoir became an accepted work of art, shock became a mere sales tactic, a proven method of marketing for the savvy artist or gallery owner. Naturally, it worked. There’s a straight line from Duchamp’s bathroom humor to the coprophilia of Chris Ofili, whose elephant dung Madonna is an icon of post-modernism. Both artists shock, and yet both are innocuous: neither intends to do anything more than shock the viewer. Their “shock and awe” campaign is long on shock and short on awe.

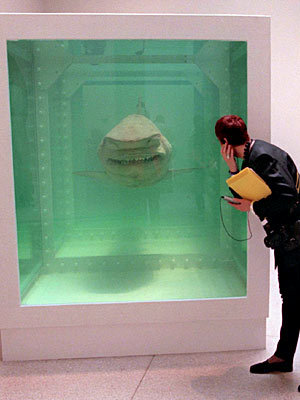

In The Eclipse of Art, British critic Julian Spalding sets out to skewer the shockers, to eviscerate the poseurs of the self-proclaimed avant garde. His special target is the YBA — the Young British Artists, whose most brilliant celebrity, Damien Hirst, is famous for pickling a shark in formaldehyde and sticking a rotting, maggot-ridden cow’s head in a glass showcase, among other aesthetic delicacies. Hirst’s Britpack hosts such luminaries as Tracey Emin, whose unmade bed, littered with soiled knickers and sanitary napkins, was a runaway hit at the Tate Modern; Sarah Lucas, whose cigarette-covered effigy of Christ at the Tate Britain is crowned with Marlboro Lights; and of course Ofili, whose elephant dung medium will one day present special problems for museum restorers. Their works betray a studied contempt for the public taste, as evidenced by Angus Fairhurst‘s sign at the Tate Britain: “Stand Still and Rot.” Their obsession with death and decay, the London Guardian declares, has made British art “synonymous with outrage and obscenity.”

In The Eclipse of Art, British critic Julian Spalding sets out to skewer the shockers, to eviscerate the poseurs of the self-proclaimed avant garde. His special target is the YBA — the Young British Artists, whose most brilliant celebrity, Damien Hirst, is famous for pickling a shark in formaldehyde and sticking a rotting, maggot-ridden cow’s head in a glass showcase, among other aesthetic delicacies. Hirst’s Britpack hosts such luminaries as Tracey Emin, whose unmade bed, littered with soiled knickers and sanitary napkins, was a runaway hit at the Tate Modern; Sarah Lucas, whose cigarette-covered effigy of Christ at the Tate Britain is crowned with Marlboro Lights; and of course Ofili, whose elephant dung medium will one day present special problems for museum restorers. Their works betray a studied contempt for the public taste, as evidenced by Angus Fairhurst‘s sign at the Tate Britain: “Stand Still and Rot.” Their obsession with death and decay, the London Guardian declares, has made British art “synonymous with outrage and obscenity.”

Charles Saatchi, Spalding observes, is the YBA’s impresario — an entrepreneur who parlayed the success of his London-based advertising firm into fame as the biggest buyer and exhibitor of modern art in Britain. Saatchi’s acquisition budget is arguably bigger than the Tate’s, and his taste is highly influential. His much-hyped Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection exalted Ofili’s Madonna, Hirst’s fast decomposing cow’s head, and a “painting” reproducing a tabloid photo of child murderer Myra Hindley. In Saatchi, Spalding notes, Hirst and company have realized the dream first articulated by the American critic Clement Greenberg: a young avant garde “attached to an umbilical cord of gold.”

The YBA’s extensive use of found objects betrays their distaste for more traditional means of making art. You can’t blame the Britpack for that: found objects are a friendly, easily forgiving medium. Why bother with canvas and drawing paper when vegetable dildos and slaughtered bovines are ready at hand? It is easier to use cucumbers to signify the male form, as Lucas did in Au Naturel, than to draw, paint or sculpt that form; and it is easier still to make twelve cows’ heads signify the Apostles, as Hirst did in his London gallery last year, than to limn their saintly features with oil or tempera.

The Britpack disdains fine drawing, and it shows in its members’ work. Their lines are tremulous, their contours uncertain, their forms vague and unsubstantial. You wonder if — as the critic Robert Hughes said of the talentless Julian Schnabel — “the cackhandedness is not feigned, but real.” Which may explain why Hirst resorts to taxidermy and Ofili to elephant dung: their mastery of drawing and other key disciplines is open to debate.

But what grates is not the YBA’s questionable competency in certain basic skills. It is rather, as Spalding says, that its members stand outside the continuum of art — and that they do so deliberately. The shock of their art triggers no catharsis. Their bisected calves and piles of bronzed rats are not designed to enlighten, and certainly not to please. When they do come to grips with the great tradition — with the continuum of art and the artists who fashioned it – the confrontation is farcical. Hirst trumps Da Vinci by depicting the Apostles as so many cows’ heads; the Chapman Brothers one-up Goya by defacing prints from his Disasters of War, as if they were spray can taggers vandalizing a street mural. The results are mystifying. As one British critic wrote of the Chapman Brothers’ effort: “Everything odd and inexplicable about Goya rushes to the foreground. And everything that was a timeless humane truth about horror and atrocity seeps away.”

The Marxist critic Ernst Fischer, writing in The Necessity of Art, denounced the chic nihilism of artists of Hirst’s ilk: “In condemning and denying everything,” Fischer observed, the artist who embraces nihilism “condones [the bourgeois] world as a setting for universal wretchedness. . . . The radical tone of the nihilist’s accusation strikes ‘revolutionary’ echoes,” but it “channels revolt into purposelessness . . . and passive despair.”

The members of the YBA mock the concept of a continuum of art, within which the radical and the traditional hold an incessant dialogue. Their experiments are stillborn, like the six-legged calf that Hirst showed off in a recent London exhibition. And like the other freaks suspended in Hirst’s showcases, their “one-off shockers” will, ultimately, stand still and rot.

Dean Ferguson is an editor of Transformation, a newly launched literary journal. He lives and works in San Francisco.

|

| Print