“Predictions are suspect. But something new is happening. . . .” — Paul Buhle1

A people’s movement against the “class war from above” is beginning to crystallize across Thailand. Students and unionized workers have suddenly emerged as a new force in the streets in helping to organize a broad-based people’s alliance to oust the ever more dictatorial neo-con billionaire prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Thaksin remains Washington’s favorite leader in East Asia. The current struggle against his authoritarian abuses in Thailand is sparking demands — and galvanizing new public awareness — about the hands-on destruction of democracy by a powerful Thai plutocracy.

The student movement has gone from almost total dormancy to mounting activism in the course of 10 days in February, in part reinvigorating a national organization, the Student Federation of Thailand, that has been largely inactive since the early 1990s. A new nationwide People’s Alliance for Democracy has been formed to pressure the prime minister to step down. Students at Thammasat University in Bangkok have launched a campaign to gather 50,000 signatures, the instrument to initiate an impeachment procedure against Thaksin.

Ever more Thai university teachers are joining this upsurge of anger and a demand for democratic renewal. At Silpakorn University, for example, a group of 77 lecturers signed a statement on February 11 demanding that the prime minister step down. They said, “Thaksin has abused the principles of the Constitution and the people’s spirit,” and accused him of “abusing power by exploiting laws to support his family and business network, destroying press freedom and disrupting independent bodies’ work.”2 Does that sound familiar to American ears?

A Populist Groundswell

Though present sentiment in this movement is not explicitly anti-capitalist, it directly targets what Upton Sinclair called the “rule of society by organized greed” and our “civilization of class privilege.” Thais know this at a very gut level. Indeed, the present Thai system is a textbook lesson in neo-con capitalist rule, no holds barred, and its inevitable excesses.

The movement now building across the Thai campuses and labor unions, among journalists, professionals, farmers, is populist and anti-corporate: against Thaksin and what he represents. There is no organized socialist opposition in Thailand, aside from the grassroots work of the still small Workers Democracy Group (Klum Prachatipatai Rangarn), an affiliate of the International Socialist Tendency. There is in Thailand no labor party, no Green party, no electoral counterpart to the Thai NGO Assembly of the Poor. But the Thai working class is fighting on a spectrum of fronts, as reflected in the Thai Labour Campaign web site: <http://www.thailabour.org/>. Class-struggle syndicalism like that of the IWW is badly needed.

Shades of a Militant Past: the Student/Worker Revolt 1973

The now revitalizing student movement has also reawakened the direct memory of the student-led Great Revolt of 1973, which toppled the then military dictatorship. That upsurge was in part also centered at Thammasat University.

On October 13, 1973, more than 250,000 people gathered in protest in Bangkok to press their grievances for a more democratic constitution and genuine elections against the military government, closely allied with Washington. The movement was led by students and workers. On October 14, troops opened fire on the demonstrators, killing seventy-five, and occupied the campus of Thammasat University. King Bhumibol took a direct role in dealing with the crisis, forcing the prime minister General Thanom to resign. In consultation with student leaders, the king appointed the rector of Thammasat University, Sanya Dharmasakti, as interim prime minister, with instructions to draft a new constitution.

Prime Minister Sanya gave full credit to the student movement for bringing down the military dictatorship.3 But 1976 brought a new military coup, and some 5,000 students went into the jungles of the Thai north and far south to join the then still powerful Communist (CPT)-led insurgency.4 That insurgency was crushed in the 1980s.

A Shared Legacy of Struggle

All this is being recalled today in the Thai student movement, just as the newly reorganizing SDS in the states simultaneously is now re-appropriating its own history, so bound up with American imperialism in Southeast Asia 40 years ago. Key U.S. bases for the war against Vietnam and the “secret war” in Laos were located in Thailand, and Washington pumped huge funding (hundreds of millions) into the Thai counter-insurgency operations from 1951 to the mid-1970s.

Belusconi on Mekong

Thaksin, a telecoms tycoon and by far Thailand’s richest man, created the fiercely neo-liberal party Thai Rak Thai (Thais Love Thais) in 1998 and has been at the helm as prime minister since January 2001. Under Thaksin’s reign, dubbed “Thaksinocracy,” politics, bureaucracy, and business have become ever more closely intertwined, breeding mega-corruption.

His government has until recently appeared to be well-entrenched, especially in the rural and urban Thai north and the central provinces, initiating pork-barrel schemes such as micro-loans to villagers. As a media mogul, Thaksin is adept at “public relations magic” and the packaging at the grassroots of his own “great CEO” image. Despite strong opposition from organized labor and the Campaign for Popular Democracy, he was re-elected by a landslide in 2005, with widespread allegations of vote-buying in the countryside. The only other major party, the Democrats, likewise neo-con in orientation, made a poor showing outside the Thai south, their traditional electoral stronghold. Thai voters, like most Americans, had little choice but to pick between two avowedly corporate parties, a familiar duopoly.

Shin Corporation Mega-Scandal

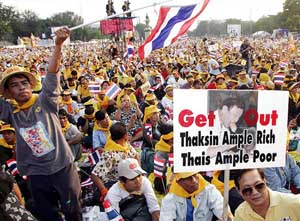

Photo by Chaiwat Subprasom |

Thaksin’s family-run Shin Corp. has investments in numerous sectors including mobile phone and satellite services, aviation, property, finance and silk. He and family members recently sold off the Shin Corp. to Temasek Holdings (Singapore) in a 2-billion-dollar super-deal, with suspicions of tax fraud and insider trading. A large hunk of the shares that were sold came from Ample Rich, a firm registered in the British Virgin Islands, which allegedly sold its shares to two of Thaksin’s children for 1 baht (2.5 cents US) per share; they then sold these a few days later to Temasek for 49 baht per share, tax-free. This has angered much of the nation and has helped to further fuel the growing protest alliance to end his rule.5 The public furore over this “deal” by Thailand’s master wheeler-dealer has been an elementary lesson for the Thai masses in the machinations of international finance capital. Thaksin remains defiant and has also tried to block media reporting on the burgeoning movement of protest against him.

In Tsunami’s Wake

Criticism of the failure of his government to inform the population about the danger of the December 26, 2004 tsunami (there was ample time for warning) and huge profits reaped by special interests in connection with post-tsunami reconstruction along the Andaman Sea coast has also stirred public distrust and indignation.

Stop the Sell-Off of the Nation

The current “remove Thaksin and his cronies” campaign was launched by a huge protest rally of over 100,000 in Bangkok on February 4, organized by another media tycoon bitterly opposed to Thaksin, Sondhi Limthongkul. Staged at the Royal Plaza, it was the biggest public political gathering in Thailand in 13 years, followed by another on February 11. A major rally is scheduled for February 26. Labor leader Sirichai Maingam: “We will tell the people that our previous objective of blocking the privatization of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand was not enough. Now we have to tell them about the need to stop efforts to privatize the whole of Thailand.” He said he was planning to hook up with other state enterprise labor union leaders across the country to mobilize their support and publicize the cause of saving the country from the prime minister.6

The Broader Context: NO to the FTA!

| Demonstrations against the FTA Agreement Thailand-Bangkok, Chiang Mai, 9-10 January 2006 |

In January 2006, some 10,000 gathered in the city of Chiang Mai to protest closed-door (!) talks on a Thai-US Free Trade Agreement. Eleven people’s alliances and many activists demanded a stop to privatizing Thailand, NO! to a Bangkok-Washington FTA, and called for the promotion of a “just economy.” These alliances included the Thai People’s Network Against Free Trade Area and Privatization, consisting of the Thai Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS, the Alternative Agriculture Network, the Council of People Organizations of Thailand, the Assembly of the Poor, the Student Federation of Thailand, and other groups.7

A letter was sent to George Bush on January 10: “The FTA between the US and Thailand will only benefit businessmen, and in particular investors. But workers, farmers and the majority of Thais would not gain anything from it but increased suffering and unstable lives.”

That protest against globalization sent a powerful message to ruling elites in both Washington and Bangkok. These Thai groups understand only too well the contours of hegemony and how imperial elites operate.

The Thai Far South on Fire

Another reason for public anger is that the Thaksin government has been unable to find some solution to the sustained and re-intensified Muslim insurgency in the four most southern Thai provinces, which has left hundreds dead, including many educational workers, over the past two years.

It is part of a political struggle in response to decades of government oppression, going back in part to 1909, when the border between Siam and British-controlled Malaya was drawn, which by fiat from above included a large ethnic Malay Muslim population within the boundaries of the Thai state. So a finger of Western colonialism was in that unresolved problem. It is a movement for greater voice and local autonomy — not necessarily separatism — as demanded by PULO (Pattani United Liberation Organization) and BERSATU (United Front), the two major guerrilla groups — in a region of Thailand ethnically and culturally distinct and generally impoverished.8

But Washington is watching this Muslim liberation movement in the troubled Thai south with an American-eagle eye and aiding Thaksin’s government, possibly assisted by Israeli military advisors, in training the Thai army in counter-insurgency techniques. Part of the Bush administration’s “war on terror” by proxy in Southeast Asia. The result to date has been predictably disastrous, with ever more bloodshed and anger.

Dr. Wan Kadir, who recently stepped down as head of BERSATU, stressed: “I never allowed for the use of violent tactics . . . if I am asked to take part in the discussions and dialogue I would be willing to do so, as I truly wish to see an end to this destruction and fighting.”9 The Thaksin government is not listening.

Education for Passivity

SHADOWED COUNTRY by Pira Sudham BUY THIS BOOK |

Thailand is a country where many institutions, including the schools, have de-politicized almost everybody. As Thai writer Pira Sudham wrote recently in the “dedication” to his new novel Shadowed Country, after growing up in the Thai province of Buriram, he chose to leave Thailand to “become a thinking person. I must rebuild my mind that has been maimed and stunted during the formative years by a feudal education, aimed at inducing subservience and mindlessness. We were supposed to become unthinking, obedient, silent and submissive so as to be governable, exploitable and harmless. We were not to have inquiring minds and critical thinking. We must not be opinionated, forthright, opposing the authorities in any way.” The present renewed student upsurge is also a protest against that inculcation of passivity and deference to authority so strong in traditional Thai culture and education, even today.

Two Nations, Rich and Poor

What is driving the public mobilization is a deep disgust for the lies and super-greed of those in power. And the widening gap between the “educated” meritocracy and the great masses of people, often barely surviving on the official minimum daily wages of 130 baht (3.25 USD) in provincial areas and 170 baht (4.25 USD) in Bangkok. Students are frequently employed seasonally at similar exploitative wages in the tourist industry, even in posh resorts and restaurants. Many households in villages in the Thai south and northeast have monthly incomes of 125 USD, dropping to even less during the extended monsoon.

The links in global Capital that are choking the Thai people and cementing an ever widening chasm between the wealthy few and the multitude are clear to growing numbers of Thais. This has been strongly impressed on the Thai public sphere in early 2006. An extraordinary chemistry of consciousness-raising is now underway, with students increasingly at its catalytic center.

There is no SDS in Thailand, but the student organization now being recreated in the U.S. could inspire some Thai students — and veterans of the 1973 Student/Worker Revolt — to move in similar directions, recovering past militancy and forging a movement for far more direct and decentralized democracy. And the groundwork for a genuinely participatory, worker-controlled economy.

References

1 Paul Buhle, “New Links for the Global Left?” MRZine: 3 November 2005.

2 See “Students Back on Centre Stage,” The Nation 13 February 2006; “Drive Spreads to 5 Universities,” The Nation 10 February 2006; and “Anti-Thaksin Alliance Grows,” The Nation 6 February 2006.

3 “Students Revolt in Thailand 1973,” OnWar.com, 16 December 2000.

4 “Thailand — Insurgency,” Exploits.com.

5 “Shin Corp Share Sale: PM ‘Condoned Dodgy Deal’,” The Nation 28 January 2006.

6 “Grass-roots Crucial to Thaksin’s Political Fate,” The Nation 13 February 2006.

7 “10,000 Protest US-Thai FTA Talks,” Bangkok Post 8 January 2006. and “Eleven People’s Alliances and Ten of Thousands Activists Demand a Stoppage of Negotiation on Life-Cr,” Focus on the Global South, 10 January 2006.

8 Farish A. Noor gives an informed analysis of the conflict in “Southern Thailand: A Bloody Mess about to Get Bloodier,” Islamic Human Rights Comission, 30 April 2004.

9 Farish A. Noor, “Dr. Wan Kadir Announces Decision to Retire and Return to Native Land!” (Interview with Wan Kadir), Brand New Malaysian, July 5, 2005.

Noknoi Daeng is the nom de guerre of a writer based in Thailand.