A Review of “Nuestro Himno,” in Somos Americanos, Urban Box Office (www.ubo.com) $10 ($1 goes to support the immigrant rights movement). Release date May 16, 2006

A Spanish-language version of the US national anthem was distributed to radio stations Friday, April 29th, in time to be played over the air to build the May 1st “Day without Immigrants” — a day of protests, strikes, and a national boycott organized by the new immigrant rights movement. The song plays when you visit the UBO website.

If you listen to it carefully, you will hear what promise this new movement holds.

The anthem was produced by Urban Box Office, a small New York-based Urban Latin and Reggaeton music label. It features the voices of Wyclef Jean, Gloria Trevi, hip-hop star Pitbull, Puerto Rican singers Carlos Ponce and Olga Tanon, and incorporates Latin rhythms while remaining faithful to the instrumental structure of what was originally an eighteenth-century English drinking tune. From a strictly musical point of view, it is a beautiful rendition.

The song was met on its release by a torrent of abuse. Bush said that the anthem should only be sung in English and that he feared the country was losing “our national soul.” In defense of Nuestro Himno, its British-born producer Adam Kidron (son of Marxist theorist Michael Kidron) explained that the version was not an exact translation of the national anthem, but that it nevertheless conveyed the same values: “the idea would be to interpret . . . what the patriotism means so the people who want so badly to be American can understand what this song is about.”

But the very existence of Nuestro Himno has incensed the American Right, which fears, in the words of The Washington Post, a “nightmare scenario of a Canada-like land with an anthem sung in two languages.” That the anger appears to be targeted at the fact that this version is sung in Spanish would suggest, however, that they haven’t yet listened to the lyrics.

Some explanation is required. The English-language anthem expresses national pride at the successful defense of Baltimore during the War of 1812. After a failed nighttime assault by the British (“the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air”), the fort defending the town continues to fly the stars and stripes into the early hours of the dawn (“O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave/O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”).

The new, Spanish version also alludes abstractly to a battle and a flag waving in the dawn, to stars and stripes and the land of liberty. It begins, however, with the invocation of “Latinos, Latinas!/Brothers, Sisters!” The claim that “We are all equal/We are brothers/This is our own anthem” (Somos iguales/Somos hermanos/Es nuestro himno) is a further departure from the original source. More surprising is the interjection — towards the end of the anthem and couched between verses describing a fierce battle for liberty — “My people continue to struggle/Now is the time to break the chains” (Mi gente sigue luchando/Ya es tiempo de romper las cadenas).

At first these verses seem to be extraneous to the loose translation of the traditional anthem. What, after all, do they have to do with the successful defense of a land which was considered already to be free in the early nineteenth century?

| “Two-thirds of Americans don’t know all the words [of the national anthem] in English. Of the one-third who claim they do, only 39 percent, according to a Harris poll, can correctly sing the phrase that follows “whose broad stripes and bright stars” (answer: “through the perilous fight”)” (“Nuestro Himno: O Nap S-ap Neid Mo An Ke:k S’alig Tonlig Ta:gio?” Editorial, Washington Post, 4 May 2006: A24). |

The original verses by Francis Scott Key do not give voice to the value of equality. The value that it does articulate in the (often omitted) third verse — pride in republican freedom (“No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave”) — is ambiguous (what did it mean to sing a hymn to republican freedom in a country of masters and slaves, settlers and Indians, as well as middling sorts?) and hardly resonates today in a nation of wage slaves who do not realize that they are. The moment in the formation of the United States that gave birth to its verses being one of the forgotten wars, the anthem, like the flag it salutes, is implicitly made to carry a specific political content: loyalty to the white, Anglo empire.

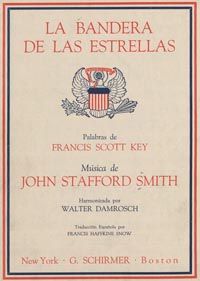

Nuestro Himno causes anxiety not simply because it is in Spanish, but because it subverts this political content — in Bush’s words it threatens the definition of the “national soul.” After all, a Spanish version of the anthem already exists. The US government itself produced a literal translation — “La Bandera de las Estrellas” (The Flag of the Stars) — in 1919. You can find a copy on the State Department’s website.

Nuestro Himno causes anxiety not simply because it is in Spanish, but because it subverts this political content — in Bush’s words it threatens the definition of the “national soul.” After all, a Spanish version of the anthem already exists. The US government itself produced a literal translation — “La Bandera de las Estrellas” (The Flag of the Stars) — in 1919. You can find a copy on the State Department’s website.

But Nuestro Himno is not La Bandera de las Estrellas. It was made for the movement, for this battle. It expresses the courage of those who participate in it and the liberty that they are demanding. It has everything to do with breaking chains and nothing to do with the defense of Baltimore.

Ian MacDonald is a PhD student at York University, Toronto, and is currently a visiting researcher at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York.