For some time, business and government leaders in the United States have aggressively promoted policies designed to expand opportunities for private profit making. The result has been growing instabilities and inequalities. Many opposed to this development have called for the imposition of controls on private production, investment, and price decisions. However, those in power routinely dismiss such ideas as unworkable. Significantly, history offers evidence to the contrary, even for the United States. One rarely-discussed example involves the successful use of price controls during World War II.

Most economic historians agree that the three most important economic achievements during the war years were the elimination of unemployment, the rapid boost in military production, and the maintenance of relatively stable prices. In fact, the government’s achievement of price stability was, in many ways, absolutely essential to its achievement of full employment and expanded military production.

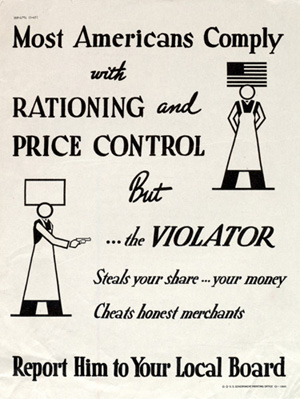

Most economists credit the government’s introduction of strict controls on the prices of many consumer goods, especially food items, for the success of its anti-inflation efforts. However, this explanation masks an even more important aspect of the control experience: price controls proved effective only when the Office of Price Administration (OPA) allowed popular participation in the organization and running of its price control system. Tens of thousands of volunteers were formally empowered to visit retail locations to monitor business compliance with the controls and tens of thousands of additional volunteers served on price boards that were empowered to fine retailers who violated the controls. In short, economic stability was achieved through a nationally coordinated and largely volunteer-implemented system of regulation that proved compatible with high levels of production and productivity. This history is worth reclaiming; it offers some important lessons for today.

The Need for Controls

The growth of the war economy in the early 1940s finally brought the depression era to a close. However, the increase in military production took place alongside a steady decline in civilian industrial production. This outcome was largely the result of corporate reluctance to increase investment and production to meet the demands of the growing civilian workforce; business leaders feared that the end of the war would bring a new recession and a renewal of excess capacity problems. This strategy greatly intensified inflationary pressures. According to Leon Henderson, the first director of the OPA, “As a result of the decrease in consumers’ goods and the increase in income payments, purchasing power in 1942 will be from 14 to 17 billion dollars greater than the value of the goods and services available.” Not surprisingly, prices soared by over 40 percent between January 1941 and December 1943.

In April 1942, the OPA responded to public demands for action by issuing the General Maximum Price Regulation (GMPR), which ordered that the prices of “all commodities and services not specifically excluded or not covered by another regulation office” be frozen at the highest level reached in March 1942, effective as of May 15. While the GMPR appeared comprehensive, it was largely unworkable. One reason was that businesses were constantly modifying existing products or introducing new ones. When that happened, procedures for determining allowable price increases were so complex that most businesses were free to do as they pleased. As a result, prices changed regularly, and there was no way for working people to determine whether businesses were complying with regulations.

Workers quickly lost patience with this situation. In 1943, with their real wages falling, some 2,000,000 went out on strike. Adding to popular anger was the fact that executive salaries and business profits were hitting record highs.

Under mounting pressure, Roosevelt directed the OPA to take new and more aggressive actions to limit price increases. His “Hold the Line” order in April 1943 ruled out any price increase affecting the cost of living unless it was determined to be “necessary to aid in the effective prosecution of the war.” The OPA ruled that what was “necessary” would be based on determination of what was an acceptable level of profit. For manufacturing, it decided that an industry would not be able to raise its prices as long as it was earning at least the same dollar amount of profits before taxes (adjusted for changes in investment) that it had earned on average in the period 1936-39, and that these earnings were enough to cover current costs on all major product lines. A similar standard was developed for retailers.

In effect, the OPA was requiring businesses to “absorb” cost increases out of profits. The business community strongly opposed this new policy. One reason is that its implementation required firms to fill out questionnaires detailing their current and pre-war costs, sales, and profits. Businesses did not like sharing this information with the government. Even more importantly, business leaders feared that this policy would lead to the creation of politically determined standards for acceptable profits, with profit controls replacing price controls.

The OPA decided to take an especially aggressive stance towards food prices, introducing dollars-and-cents ceiling prices for critical food items. In contrast to its past approach, dollars-and-cents ceiling prices could easily be understood and monitored. While some of the new ceiling prices, such as for meat, were set by the national office, prices for the majority of the 300 goods on the designated community price list were set by district offices.

More specifically, all grocery stores were divided into one of four categories based on their size and service; each category was then assigned its own nationally determined percentage mark-up. To calculate community price ceilings, OPA district offices first calculated the local production costs of each product on the list using information supplied by local suppliers. Then they applied the national mark-up to the local costs. The result was a dollars-and-cents ceiling price for each commodity that varied by type of store and community. District offices then adjusted these ceiling prices weekly for perishable items and monthly for packaged ones.

Equally important, the OPA eventually mobilized tens of thousands of volunteers to administer and ensure retail compliance with its new control system. The combination of new controls and popular participation in their application proved to be a success. Between the spring of 1943 and April 1945, consumer prices rose less than 2 percent. Thanks to subsidies and rollbacks, food prices actually declined by more than 4 percent. This record is especially noteworthy in that it was achieved over the last years of the war, when employment was at a maximum and consumer goods production highly restricted.

Popular Participation in Price Control

The OPA program involved establishing price panels throughout the nation, each of which was generally staffed by five to seven volunteers and supported by one paid clerk. The price panels had tremendous responsibilities. For example, they were supposed to educate all retail businesses, not just those selling food, about the government’s price regulations. This meant that price panel members had to be informed about price regulations for laundries, department stores, grocery stores, restaurants, and many other establishments. To carry out their educational responsibilities, panel members generally held meetings with the various retailers in their area to explain the rules and answer questions.

Price panels were also charged with investigating cases of alleged business non-compliance. The panels were instructed to investigate all consumer complaints. If a panel felt that a violation had occurred, panel members would hold a conference, normally in the evening, where both the consumer and retailer could argue their respective positions. If the panel determined that a violation had indeed taken place, the consumer had the right to collect any overcharge due, or sue in court for three times the overcharge or $50, whichever was larger.

Price panels were also charged with investigating cases of alleged business non-compliance. The panels were instructed to investigate all consumer complaints. If a panel felt that a violation had occurred, panel members would hold a conference, normally in the evening, where both the consumer and retailer could argue their respective positions. If the panel determined that a violation had indeed taken place, the consumer had the right to collect any overcharge due, or sue in court for three times the overcharge or $50, whichever was larger.

Critical to the success of the panels was the work of the volunteer price panel assistants. Their job was to check that every grocery store displayed a poster showing its assigned category, a separate poster showing the dollars-and-cents price ceilings for stores in its category, and clear signs posted near each product on the community price list showing its selling price. The assistants were also to check that selling prices were no higher than the mandated ceiling prices. If problems were found and not immediately corrected, the assistants were to report the store to the relevant price panel, which then held an investigative hearing. Although price boards initially had only limited powers to fine retailers that refused to comply with the regulations, legislation in 1944 gave them the right to sue for damages on behalf of the public. From January 1945 to June 1946, a total of 71,050 sellers were required to pay over $5.1 million to the US Treasury.

An example of the effectiveness of the control effort: The OPA ordered an emergency price check of every food store in the country during a one-week period in March 1944. Over 5,000 boards participated and over 430,000 food stores were visited. A board-by-board examination of the survey showed that, where volunteers made weekly visits, the number of stores in violation dropped to 4 percent; where there were no regular visits, as many as 75 percent of the stores were found to be overcharging.

This success only intensified business opposition to the OPA program. Business leaders feared that the combination of the absorption principle and direct popular monitoring of their operations could easily lead to new and more direct challenges to their freedom of operation. Some used the newspapers to promote stories and cartoons depicting the OPA as a communist front organization and a threat to democracy and the Bill of Rights.

Tragically, the business community eventually succeeded in pressuring the government into dropping the price assistants in 1944. While progressives strongly supported the controls, the historical record suggests that there was little recognition that it was the direct monitoring of business behavior that had ensured their success. As a result, the left did little to defend this part of the program. When the war ended, even the controls were dropped.

Freed from wartime wage limits and no strike agreements, workers quickly launched a major strike wave to recover lost wages. However, their gains were short-lived. Without effective controls, price increases quickly outpaced wage gains, leaving most workers with lower real wages. At the same time corporate profits set new records.

Contemporary Relevance

This history has much to teach. For example, it shows that controls — on profits and prices — are workable and effective. It also shows that mass actions can force the government into implementing appropriately strong systems of control on corporate activity. It also demonstrates that working people are willing to sacrifice their time for the national interest, and that they are able to work collectively, with minimal national supervision, to regulate critical economic activities. It also highlights the fact that our criteria for evaluating public policies should include an assessment of their compatibility with, and potential to encourage, popular participation in their operation. Finally, this history also demonstrates the importance of waging a strategic and ongoing struggle to strengthen the popular will and capacity to shape and direct economic activity.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College, in Portland, Oregon, and author of The Rush to Development: Economic Change and Political Struggle in South Korea and Korea: Division, Reunification, and U.S. Foreign Policy. Hart-Landsberg co-authored (with Paul Burkett) China and Socialism: Market Reforms and Class Struggle (Monthly Review Press, 2005).

Martin Hart-Landsberg is professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College, in Portland, Oregon, and author of The Rush to Development: Economic Change and Political Struggle in South Korea and Korea: Division, Reunification, and U.S. Foreign Policy. Hart-Landsberg co-authored (with Paul Burkett) China and Socialism: Market Reforms and Class Struggle (Monthly Review Press, 2005).