Mariátegui’s funeral was one of the largest processions of workers ever seen in the streets of Lima, Peru, but in the U.S. his death was hardly noticed.

In 1930, Waldo Frank wrote in the leftist U.S. weekly the Nation that the April 16 death of Jose Carlos Mariátegui had plunged “the intelligentsia of all of Hispano-America into sorrow; and nothing could be more eloquent of the cultural separation between the two halves of the new world than the fact that to most of us these words convey no meaning.”

His funeral turned into one of the largest processions of workers ever seen in the streets of Lima, Peru, but in the United States his death was hardly noticed. Unfortunately, 87 years later Mariátegui is still largely unknown in the English-speaking world, even as his status as the founder of Latin American Marxism remains as relevant as ever for understanding political changes sweeping across the region.

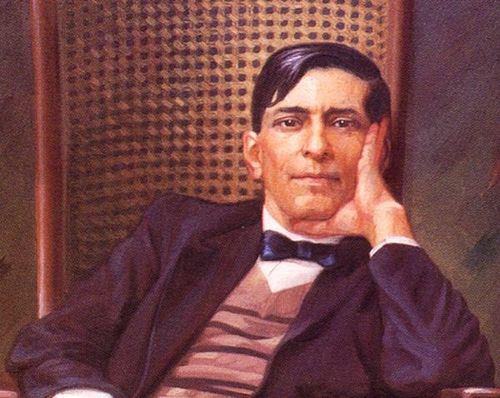

Mariátegui was born in the small southern Peruvian town of Moquegua on June 14, 1894, the sixth child of a poor mestiza woman, Maria Amalia LaChira. Mariátegui was a weak and sickly child. From an early age he had developed a tubercular condition, and when he was eight years old he hurt his left leg, which crippled him for life. Because of a lack of financial resources and the need to support his family, he acquired only an eighth-grade education. At the age of 15, Mariátegui began work at the Peruvian newspaper La Prensa. Throughout his life, Mariátegui used his journalism skills as both a financial livelihood as well as a vehicle for expressing his political views.

Mariátegui’s vocal support for the revolutionary demands of workers and students ran him afoul of the Peruvian dictator Augusto B. Leguia, who in October 1919, exiled him to Europe. From 1919 to 1923, Mariátegui studied in France and Italy where he interacted with many European socialists. The time in Europe strongly influenced the development and maturation of his thought, and solidified his socialist tendencies. Upon returning to Peru in 1923, Mariátegui declared that he was “a convinced and declared Marxist.” Mariátegui later looked back on his early life as a journalist as his “stone age” in contrast to his later writings when he had matured as a Marxist thinker.

Mariátegui interacted dynamically with European thought in order to develop new methods to analyze Latin American problems. He implemented a new theoretical framework that broke from a rigid, orthodox interpretation of Marxism in order to develop a creative Marxist analysis that was oriented toward Peru’s specific historical reality. He favored a non-sectarian “open” Marxism and believed that Marxist thought should be revisable, undogmatic, and adaptable to new situations. Rather than a rigid reliance on objective economic factors to foment a revolutionary situation, Mariátegui also examined subjective elements such as the need for the political education and organization of the working-class proletariat, a strategy that he believed could move a society to revolutionary action.

Mariátegui was an intellectual at odds with the academic world. Although he lacked a formal education, he had a creative and brilliant mind. In 1926, he founded Amauta, a journal that he intended to be a vanguard voice for an intellectual and spiritual movement to create a new Peru. Amauta reached a wide audience not only in Peru but throughout Latin America. In 1928, Mariátegui launched a biweekly periodical called Labor to inform, educate, and politicize the working class. He also published two books, “La escena contemporanea” (“The Comtemporary Scene”) in 1925 and “7 ensayos de interpretación de la realidad peruana” (“Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality”) in 1928, in addition to many articles in various Peruvian periodicals.

Mariátegui is best known for his second book, which contains seven essays on the topics of economic development, Indigenous peoples, land distribution, the education system, religion, and literature. It was critically acclaimed for its original and creative insights into Latin American reality. Mariátegui presents a brilliant analysis of Peruvian, and by extension Latin American, problems from a Marxist point of view. It is a foundational work on Latin American Marxism and commonly cited as the one book everyone should read to understand Latin American realities.

Unlike orthodox Marxists who believed that peasants formed a reactionary class, Mariátegui looked to the rural Indigenous masses in addition to an industrialized urban working class to lead a social revolution that he believed would sweep across Latin America. Mariátegui argued that once Indigenous peoples had seized onto socialism, they would cling to it fervently, since it coincided with traditionally based communal feelings. To be successful, modern socialism would fuse the legacy of “Inka communism” with modern western technology.

Mariátegui’s revolutionary activities did not remain only on a theoretical level. He organized communist cells all over Peru and served as the first secretary general of the Peruvian Socialist Party that he founded in 1928. In 1929, the PSP launched the General Confederation of Peruvian Workers, a Marxist-oriented trade union federation. Both the CGTP and the PSP were involved in an active internationalism, including participating in Communist International-sponsored meetings. Twice the Augusto B. Leguia dictatorship arrested and imprisoned Mariátegui for his political activities, although he was never convicted of any crime.

Although the political party and labor confederation that Mariátegui had helped launch flourished, his health floundered. In 1924 he had lost his right leg and was confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. In spite of his failing health, Mariátegui increased the intensity of his efforts to organize a social revolution in Peru. He was at the height of his intellectual and political contributions when he died on April 16, 1930, two months short of his 36th birthday. Unfortunately, after his death, the movement that Mariátegui had founded lost its vitality and its revolutionary potential. With the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, a new generation of activists rediscovered Mariátegui’s thought. More than 50 years later, the founder of Latin American Marxism continues to inspire revolutionaries to rethink and reimagine new ways of confronting problems of political and economic exclusion and social injustice.