In August, after a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville ended in murder, Steve Bannon insisted that “there’s no room in American society” for neo-Nazis, neo-Confederates, and the KKK.

But an explosive cache of documents obtained by BuzzFeed News proves that there was plenty of room for those voices on his website.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, under Bannon’s leadership, Breitbart courted the alt-right — the insurgent, racist right-wing movement that helped sweep Donald Trump to power. The former White House chief strategist famously remarked that he wanted Breitbart to be “the platform for the alt-right.”

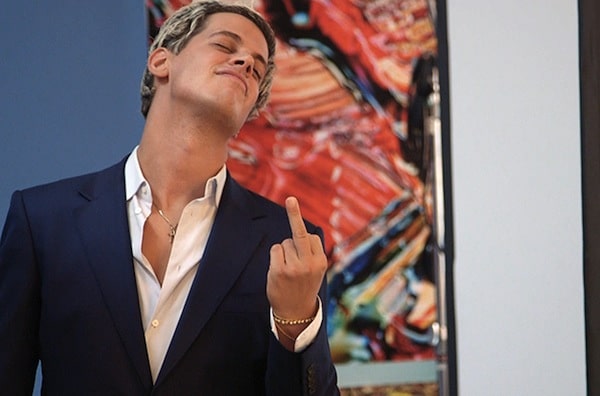

Milo Yiannopoulos at the University of California, Berkeley, on September 24, 2017. Josh Edelson / AFP / Getty Images.

The Breitbart employee closest to the alt-right was Milo Yiannopoulos, the site’s former tech editor known best for his outrageous public provocations, such as last year’s Dangerous Faggot speaking tour and September’s canceled Free Speech Week in Berkeley. For more than a year, Yiannopoulos led the site in a coy dance around the movement’s nastier edges, writing stories that minimized the role of neo-Nazis and white nationalists while giving its politer voices “a fair hearing.” In March, Breitbart editor Alex Marlow insisted “we’re not a hate site.” Breitbart’s media relations staff repeatedly threatened to sue outlets that described Yiannopoulos as racist. And after the violent white supremacist protest in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August, Breitbart published an article explaining that when Bannon said the site welcomed the alt-right, he was merely referring to “computer gamers and blue-collar voters who hated the GOP brand.”

These new emails and documents, however, clearly show that Breitbart does more than tolerate the most hate-filled, racist voices of the alt-right. It thrives on them, fueling and being fueled by some of the most toxic beliefs on the political spectrum — and clearing the way for them to enter the American mainstream.

It’s a relationship illustrated most starkly by a previously unreleased April 2016 video in which Yiannopoulos sings “America the Beautiful” in a Dallas karaoke bar as admirers, including the white nationalist Richard Spencer, raise their arms in Nazi salutes.

These documents chart the Breitbart alt-right universe. They reveal how the website — and, in particular, Yiannopoulos — links the Mercer family, the billionaires who fund Breitbart, to underpaid trolls who fill it with provocative content, and to extremists striving to create a white ethnostate.

They capture what Bannon calls his “killing machine” in action, as it dredges up the resentments of people around the world, sifts through these grievances for ideas and content, and propels them from the unsavory parts of the internet up to TrumpWorld, collecting advertisers’ checks all along the way.

And the cache of emails — some of the most newsworthy of which BuzzFeed News is now making public — expose the extent to which this machine depended on Yiannopoulos, who channeled voices both inside and outside the establishment into a clear narrative about the threat liberal discourse posed to America. The emails tell the story of Steve Bannon’s grand plan for Yiannopoulos, whom the Breitbart executive chairman transformed from a charismatic young editor into a conservative media star capable of magnetizing a new generation of reactionary anger. Often, the documents reveal, this anger came from a legion of secret sympathizers in Silicon Valley, Hollywood, academia, suburbia, and everywhere in between.

“I have said in the past that I find humor in breaking taboos and laughing at things that people tell me are forbidden to joke about,” Yiannopoulos wrote in a statement to BuzzFeed News. “But everyone who knows me also knows I’m not a racist. As someone of Jewish ancestry, I of course condemn racism in the strongest possible terms. I have stopped making jokes on these matters because I do not want any confusion on this subject. I disavow Richard Spencer and his entire sorry band of idiots. I have been and am a steadfast supporter of Jews and Israel. I disavow white nationalism and I disavow racism and I always have.”

He added that during his karaoke performance, his “severe myopia” made it impossible for him to see the Hitler salutes a few feet away.

Steve Bannon, the other Breitbart employees named in the story, and the Mercer family did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Like all the new media success stories, Breitbart’s alt-right platform depends on the participation of its audience. It combusts the often secret fury of those who reject liberal norms into news, and it doesn’t burn clean.

Now Bannon is back at the controls of the machine, which he has said he is “revving up.” The Mercers have funded Yiannopoulos’s post-Breitbart venture. And these documents present the clearest look at what these people may have in store for America.

Protesters at a white supremacist rally at the University of Virginia on August 11. Nurphoto / Getty Images.

A year and a half ago, Milo Yiannopoulos set himself a difficult task: to define the alt-right. It was five months before Hillary Clinton named the alt-right in a campaign speech, 10 months before the alt-right’s great hope became president, and 17 months before Charlottesville clinched the alt-right as a stalking horse for violent white nationalism. The movement had just begun its explosive emergence into the country’s politics and culture.

At the time, Yiannopoulos, who would later describe himself as a “fellow traveler” of the alt-right, was the tech editor of Breitbart. In summer 2015, after spending a year gathering momentum through GamerGate — the opening salvo of the new culture wars — he convinced Breitbart upper management to give him his own section. And for four months, he helped Bannon wage what the Breitbart boss called in emails to staff “#war.” It was a war, fought story by story, against the perceived forces of liberal activism on every conceivable battleground in American life.

Yiannopoulos was a useful soldier whose very public identity as a gay man (one who has now married a black man) helped defend him, his anti-political correctness crusade, and his employer from charges of bigotry.

But now Yiannopoulos had a more complicated fight on his hands. The left — and worse, some on the right — had started to condemn the new conservative energy as reactionary and racist. Yiannopoulos had to take back “alt-right,” to redefine for Breitbart’s audience a poorly understood, leaderless movement, parts of which had already started to resist the term itself.

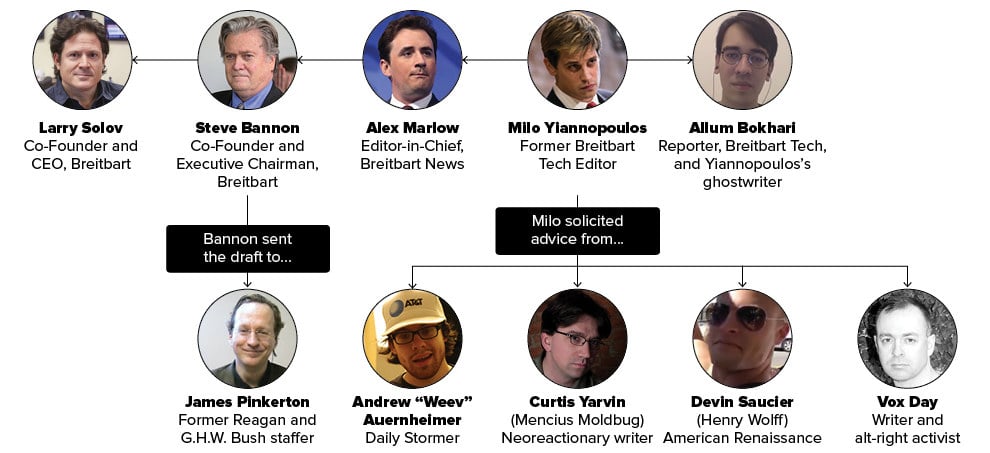

So he reached out to key constituents, who included a neo-Nazi and a white nationalist.

“Finally doing my big feature on the alt right,” Yiannopoulos wrote in a March 9, 2016, email to Andrew “Weev” Auernheimer, a hacker who is the system administrator of the neo-Nazi hub the Daily Stormer, and who would later ask his followers to disrupt the funeral of Charlottesville victim Heather Heyer. “Fancy braindumping some thoughts for me.”

“It’s time for me to do my big definitive guide to the alt right,” Yiannopoulos wrote four hours later to Curtis Yarvin, a software engineer who under the nom de plume Mencius Moldbug helped create the “neoreactionary” movement, which holds that Enlightenment democracy has failed and that a return to feudalism and authoritarian rule is in order. “Which is my whorish way of asking if you have anything you’d like to make sure I include.”

“Alt r feature, figured you’d have some thoughts,” Yiannopoulos wrote the same day to Devin Saucier, who helps edit the online white nationalist magazine American Renaissance under the pseudonym Henry Wolff, and who wrote a story in June 2017 called “Why I Am (Among Other Things) a White Nationalist.”

The three responded at length: Weev about the Daily Stormer and a podcast called The Daily Shoah, Yarvin in characteristically sweeping world-historical assertions (“It’s no secret that North America contains many distinct cultural/ethnic communities. This is not optimal, but with a competent king it’s not a huge problem either”), and Saucier with a list of thinkers, politicians, journalists, films (Dune, Mad Max, The Dark Knight), and musical genres (folk metal, martial industrial, ’80s synthpop) important to the movement. Yiannopoulos forwarded it all, along with the Wikipedia entries for “Alternative Right” and the esoteric far-right Italian philosopher Julius Evola — a major influence on 20th-century Italian fascists and Richard Spencer alike — to Allum Bokhari, his deputy and frequent ghostwriter, whom he had met during GamerGate. “Include a bit of everything,” he instructed Bokhari.

“I think you’ll like what I’m cooking up,” Yiannopoulos wrote to Saucier, the American Renaissance editor.

“I look forward to it,” Saucier replied. “Bannon, as you probably know, is sympathetic to much of it.”

Five days later Bokhari returned a 3,000-word draft, a taxonomy of the movement titled “ALT-RIGHT BEHEMOTH.” It included a little bit of everything: the brains and their influences (Yarvin and Evola, etc.), the “natural conservatives” (people who think different ethnic groups should stay separate for scientific reasons), the “Meme team” (4chan and 8chan), and the actual hatemongers. Of the last group, Bokhari wrote: “There’s just not very many of them, no-one really likes them, and they’re unlikely to achieve anything significant in the alt-right.”

“Magnificent start,” Yiannopoulos responded.

Over the next three days, Yiannopoulos passed the article back to Yarvin and the white nationalist Saucier, the latter of whom gave line-by-line annotations. He also sent it to Vox Day, a writer who was expelled from the board of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America for calling a black writer an “ignorant savage,” and to Alex Marlow, the editor of Breitbart.

“Solid, fair, and fairly comprehensive,” Vox Day responded, with a few suggestions.

“Most of it is great but I don’t want to rush a major long form piece like this,” Marlow wrote back. “A few people will need to weigh in since it deals heavily with race.”

Also, there was another sensitive issue to be raised: credit. “Allum did most of the work on this and wants joint [byline] but I want the glory here,” Yiannopoulos wrote back to Marlow. “I am telling him you said it’s sensitive and want my byline alone on it.”

Minutes later, Yiannopoulos emailed Bokhari. “I was going to have Marlow collude with me … about the byline on the alt right thing because I want to take it solo. Will you hate me too much if I do that? … Truthfully management is very edgy on this one (They love it but it’s racially charged) and they would prefer it.”

“Will management definitely say no if it’s both of us?” Bokhari responded. “I think it actually lowers the risk if someone with a brown-sounding name shares the BL.”

Five days later, March 22nd, Marlow returned with comments. He suggested that the story should show in more detail how Yiannopoulos and most of the alt-right rejected the actual neo-Nazis in the movement. And he added that Taki’s Magazine and VDare, two publications Yiannopoulos and Bokhari identified as part of the alt-right, “are both racist. … We should disclaimer that or strike that part of the history from the article.” (The published story added, in the passive voice, “All of these websites have been accused of racism.”) Again the story went back to Bokhari, who on the 24th sent Yiannopoulos still another draft, with the subject head “ALT RIGHT, MEIN FUHRER.”

On the 27th, now co-bylined, the story was ready for upper management: Bannon and Larry Solov, Breitbart’s press-shy CEO. It was also ready, on a separate email chain, for another read and round of comments from the white nationalist Saucier, the feudalist Yarvin, the neo-Nazi Weev, and Vox Day.

“I need to go thru this tomorrow in depth…although I do appreciate any piece that mentions evola,” Bannon wrote. On the 29th, in an email titled “steve wants you to read this,” Marlow sent Yiannopoulos a list of edits and notes Bannon had solicited from James Pinkerton, a former Reagan and George H.W. Bush staffer and a contributing editor of the American Conservative. The 59-year-old Pinkerton was put off by a cartoon of Pepe the Frog conducting the Trump Train.

“I love art,” he wrote inline. “I think [Breitbart News Network] needs a lot more of it, but I don’t get the above. Frogs? Kermit? Am I missing something here?”

Later that day, Breitbart published “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide to the Alt-Right.” It quickly became a touchstone, cited in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the New Yorker, CNN, and New York Magazine, among others. And its influence is still being felt. This past July, in a speech in Warsaw that was celebrated by the alt-right, President Trump echoed a line from the story — a story written by a “brown-sounding” amanuensis, all but line-edited by a white nationalist, laundered for racism by Breitbart’s editors, and supervised by the man who would in short order become the president’s chief strategist.

The machine had worked well.

It hadn’t always been so easy.

The previous November, Yiannopoulos emailed Bannon with a bone to pick. Breitbart London reported that a London college student behind a popular social justice hashtag had threatened the anti-Islam activist Pamela Geller.

“The story is horseshit and we should never have published it,” Yiannopoulos wrote. “Reckless and stupid. … Strongly recommend we pull. it’s insanely defamatory. I spoke to pamela geller and even she said it was rubbish. We’re outright lying about this girl and surely we’re better than that. We can and should win by telling the truth.”

Six minutes later, Bannon wrote back to his tech editor in a fury. “Your [sic] full of shit. When I need your advice on anything I will ask. … The tech site is a total clusterfuck—meaningless stories written by juveniles. You don’t have a clue how to build a company or what real content is. And you don’t have long to figure it out or your [sic] gone. … You are magenalia [sic].”

(Geller clarified to BuzzFeed News in a statement that she believed it was “rubbish” that the London university characterized the threats against her as “fake.”)

On December 8, the New York Times published a major story about the radicalization of American Muslims on Facebook. Yiannopoulos published a story called “Birth Control Makes Women Unattractive and Crazy.”

That afternoon, Bannon emailed Yiannopoulos and Marlow.

“Dude—we r in a global existentialist war where our enemy EXISTS in social media and u r jerking yourself off w/ marginalia!!!! U should be OWNING this conversation because u r everything they hate!!! Drop your toys, pick up your tools and go help save western civilization.”

“Message received,” Yiannopoulos wrote back. “I will do a Week of Islam next week.”

“U don’t need that,” Bannon responded. “Just get in the fight—ur Social Media and they have made it a powerful weapon of war. … There is no war correspondent in the west yet dude and u can own it and be remember for 3 generations–or sit around wasting your God-given talents jerking off to your fan base.”

Over the next several months, Yiannopoulos began to find the right targets. First it was a continued attack on Shaun King, the writer and Black Lives Matter activist whose ethnicity Yiannopoulos had called into question. Next it was then–Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer, who Bannon called in an email to Yiannopoulos the “poster child for the narcissistic ecosystem.”

And increasingly it was enemies of Donald Trump. In response to a Yiannopoulos pitch accusing a prominent Republican opponent of Trump of being a pill-popper, Bannon wrote: “Dude!!! LMAO! … Epic.” And Bannon signed off on an April story by Yiannopoulos imploring #NeverTrumpers to get on board with “Trump and the alt-right.” (Bannon did, however, veto making it the lead story on the site, writing to Yiannopoulos and Marlow, “Looks like we have our thumb on the scale.”)

Why was Bannon so concerned with the focus of his tech editor’s energies? In a February email exchange before Yiannopoulos appeared on Greg Gutfeld’s Sunday Fox News show, Bannon wrote, “Gutfeld should become an object lesson for u. Brilliant cultural commentator who really got pop culture, the hipster scene and advant [sic] garde….got on fox and tried to become a political pundit…lost all credibility. … You r one of the potential heirs to his cultural leadership so act according.” Bannon was grooming the younger man for something greater.

In May, Bannon invited Yiannopoulos to Cannes for a week for the film festival. “Want to discuss tv and film with u,” he wrote in an email. “U get to meet my partners, hang on the boat and discuss business.”

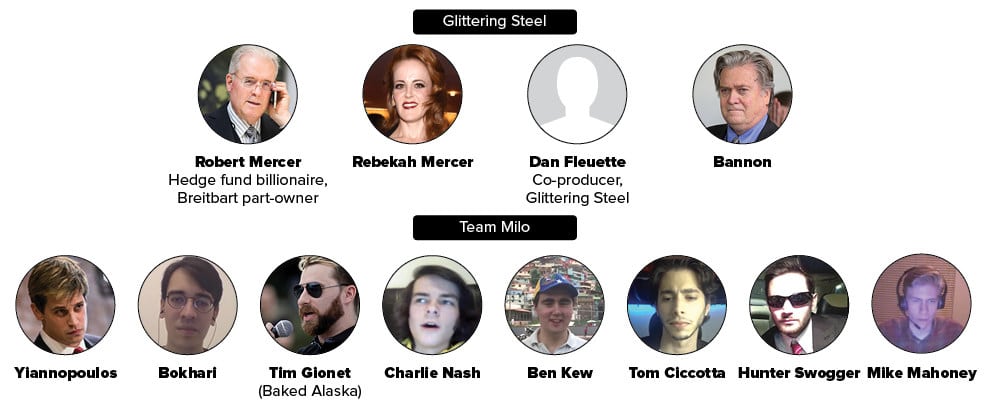

The boat was the Sea Owl, a 200-foot yacht owned by the hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer, who is a major funder of Breitbart and various other far-right enterprises. That week, Yiannopoulos shuttled back and forth from the Cannes Palace Hotel to the pier next to the Palais des Festivals et des Congrès and the green-sterned, “fantasy-inspired” vessel complete with a Dale Chihuly chandelier. The Mercers were in town to promote Clinton Cash, a film produced by Bannon and their production studio, Glittering Steel. On board, Yiannopoulos drank, mingled, and interviewed Phil Robertson, the lavishly bearded patriarch of Duck Dynasty, for his podcast.

“I know how lucky I am,” Yiannopoulos wrote to Bannon on May 20. “I’m going to work hard to make you some money — and win the war! Thanks for having me this week and for the faith you’re placing in me chief. The left won’t know what hit them.”

“U just focus on being who u are– we will put a top level team around u,” Bannon wrote back. “#war.”

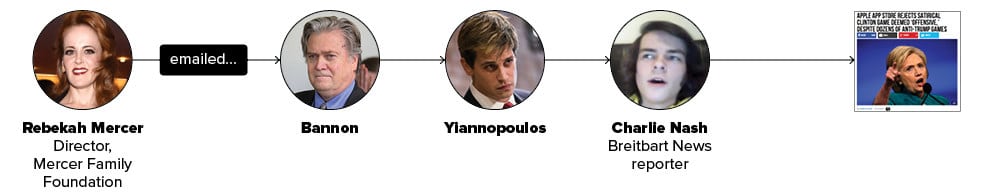

On July 22, 2016, Rebekah Mercer — Robert’s powerful daughter — emailed Steve Bannon from her Stanford alumni account. She wanted the Breitbart executive chairman, whom she introduced as “one of the greatest living defenders of Liberty,” to meet an app developer she knew. Apple had rejected the man’s game (Capitol HillAwry, in which players delete emails à la Hillary Clinton) from the App Store, and the younger Mercer wondered “if we could put an article up detailing his 1st amendment political persecution.”

Bannon passed the request from Mercer to Yiannopoulos. Yiannopoulos passed it to Charlie Nash, an 18-year-old Englishman whom he had met at a conference of the populist right-wing UK Independence Party conference the previous year, and who started working as his intern immediately after. Like some bleach-blonde messiah of anti–political correctness, Yiannopoulos tended to draw in ideologically sympathetic young men at conferences, campus speeches, and on social media, accumulating more and more acolytes as he went along.

In June 2015 it was Ben Kew, who invited Yiannopoulos to speak at the University of Bristol, where he was a student; he’s now a staff writer for Breitbart. In September 2015 it was Tom Ciccotta, the treasurer of the class of 2017 at Bucknell University, who still writes for Breitbart. In February 2016 it was Hunter Swogger, a University of Michigan student and then the editor of the conservative Michigan Review, whom Yiannopoulos cultivated and brought on as a social media specialist during his Dangerous Faggot tour. Yiannopoulos called these young researchers his “trufflehounds.”

Nash, who had just been hired by Breitbart at $30,000 a year after months of lobbying by Yiannopoulos, dutifully fielded the request from the billionaire indirectly paying his salary and turned around a story about the rejected Capitol HillAwry app on the 25th — and a follow-up five days later after Apple reversed its decision.

“Huge victory,” Bannon emailed after the reversal. “Huge win.”

This was the usual way stories came in from the Mercers, according to a former Breitbart editor: with a request from Bannon referring to “our investors” or “our investing partners.”

After Cannes, as Bannon pushed Yiannopoulos to do more live events that presented expensive logistical challenges, the involvement of the investing partners became increasingly obvious. Following a May event at DePaul University in Chicago in which Black Lives Matter protesters stormed a Yiannopoulos speech, he wrote to Bannon, “I wouldn’t confess this to anyone publicly, of course, but I was worried … last night that I was going to get punched or worse. … I need one or two people of my own.”

“Btw they are ALL ‘factories of hate.’”

“Agree 100%,” Bannon wrote. “We want you to stir up more. Milo: for your eyes only we r going to use the mercers private security company.”

Copied on the email was Dan Fleuette, Bannon’s coproducer at Glittering Steel and the man who acted for months as the go-between for Yiannopoulos and the Mercers. As Yiannopoulos made the transition in summer 2016 from being a writer to becoming largely the star of a traveling stage show, Fleuette was enlisted to process and wrangle the legion of young assistants, managers, trainers, and other talent the Breitbart tech editor demanded be brought along for the ride.

First came Tim Gionet, the former BuzzFeed social media strategist who goes by “Baked Alaska” on Twitter, whom Yiannopoulos pitched to Fleuette as a tour manager in late May. Gionet accompanied Yiannopoulos to Florida after the June 2016 Pulse nightclub killings in Orlando. The two planned a press conference outside a mosque attended by the shooter, Omar Mateen. (“Brilliant,” Bannon emailed. “Btw they are ALL ‘factories of hate.’”) But after some impertinent tweets and back talk from Gionet, Fleuette became Yiannopoulos’s managerial confidante.

“He needs to understand that ‘Baked Alaska’ is over,” Yiannopoulos wrote in one email to Fleuette. “He is not a friend he is an employee. … He is becoming a laughing stock and that reflects badly on me.” In another, “I think we need to replace Tim. … [He] has no news judgment or understanding of what’s dangerous (thinks tweets about Jews are just fine). … He seems more interested in his career as an obscure Twitter personality than my tour manager.”

At the Republican National Convention, Yiannopoulos deliberately chose a hotel for Gionet far from the convention center, writing to another Breitbart employee, “Exactly where I want him. … He needs the commute to remind him of his place.”

Gionet did not respond to multiple requests by BuzzFeed News for comment.

But Gionet, who would go on to march with the alt-right in Charlottesville, was still useful to Yiannopoulos as a gateway to a group of young, hip, social media–savvy Trump supporters.

Yiannopoulos managed all of his assistants and ghostwriters under his own umbrella, using “yiannopoulos.net” emails and private Slack rooms. This structure insulated Breitbart’s upper management from the 4chan savants and GamerGate vets working for Yiannopoulos. And it gave Yiannopoulos a staff loyal to him above Breitbart. (Indeed, Yiannopoulos shopped a separate “Team Milo” section to Dow Jones, which publishes the Wall Street Journal, in July 2016.)

It also sometimes led to extraordinarily fraught organizational and personal dynamics. Take Allum Bokhari, the Oxford-educated former political consultant whom Yiannopoulos rewarded for his years of grunt work with a $100,000 ghostwriting contract for his book Dangerous.

But the men were spying on each other.

In April 2016, Yiannopoulos asked Bokhari for “a complete list of the email, social media, bank accounts, and any other system and services of mine you have been accessing, and how long you’ve had access.” Bokhari confessed to having logged into Yiannopoulos’s email and Slack, and had used Yiannopoulos’s credit card for an Airbnb, a confession Yiannopoulos quickly passed on to Larry Solov, the Breitbart CEO.

“My basic position is that he is not stable and needs to be far away from me,” Yiannopoulos wrote to Marlow and Solov.

Meanwhile, Yiannopoulos had compiled a transcript of what he called “a short section of 30 hours of recording down on paper,” which appeared to be of conversations between Bokhari and a friend.

The newcomers brought in by Gionet weren’t much better behaved. Yiannopoulos had to boot one prospective member of his “tour squad” for posting cocaine use on Snapchat. Mike Mahoney, a then–20-year-old from North Carolina, had to be monitored because of his propensity for racism and anti-Semitism on social media. (Mahoney was later banned from Twitter, but he’s relocated to Gab, a free speech uber alles social network where he is free to post messages such as “reminder: muslims are fags.”)

“Let me know if there’s anything specific that’s really bad eg any Jew stuff,” Yiannopoulos wrote of Mahoney in an email to another member of his staff. “His entire Twitter persona will have to change dramatically once he gets the job.” On September 11, 2016, Mahoney signed a $2,500-a-month contract with Glittering Steel.

As the Dangerous Faggot tour swung into gear, Yiannopoulos grew increasingly hostile toward Fleuette, whom he excoriated for late payments to his young crew, lack of support, and disorganization. “The entire tour staff is demanding money,” Yiannopoulos wrote in one email to Fleuette in October. “No one knows or cares who Glittering Steel is but this represents a significantly damaging risk to my reputation if it gets out.” And in another, “Your problem right now is keeping me happy.”

Yet ultimately Fleuette was necessary — he connected Yiannopoulos’s madcap world and the massively rich people funding the machine.

“I think you know who the final decision belongs to,” Fleuette wrote to Yiannopoulos after one particularly frantic request for money. “I am in daily communication with them.”

Yiannopoulos’s star rose throughout 2016 thanks to a succession of controversial public appearances, social media conflagrations, Breitbart radio spots, television hits, and magazine profiles. Bannon’s guidance, the Mercers’ patronage, and the creative energy of his young staff had come together at exactly the time Donald Trump turned offensive speech into a defining issue in American culture. And for thousands of people, Yiannopoulos, Breitbart’s poster child for offensive speech, became a secret champion.

Aggrieved by the encroachment of so-called cultural Marxism into American public life, and egged on by an endless stream of stories on Fox News about safe spaces and racially charged campus confrontations, a diverse group of Americans took to Yiannopoulos’s inbox to thank him and to confess their fears about the future of the country.

He heard from ancient veterans who “binge-watched” his speeches on YouTube; from “a 58 year old asian woman” concerned about her high school daughter’s progressive teachers; from boys asking how to win classroom arguments against feminists; from a former NASA employee who said he had been “laid off by my fat female boss” and was sad that the Jet Propulsion Lab had become “completely cucked”; from a man who had bought his 11-year-old son an AR-15 and named it “Milo”; from an Indiana lesbian who said she “despised liberals” and begged Yiannopoulos to “keep triggering the special snowflakes”; from a doctoral student in philosophy who said he had been threatened with dismissal from his program for sharing his low opinion of Islam; from a Charlotte police officer thanking Yiannopoulos for his “common sense Facebook posts” about the shooting of Keith Lamont Scott (“BLUE LIVES MATTER,” Yiannopoulos responded); from a New Jersey school teacher who feared his students would become “pawns for the left social justice campaign”; from a man who said he had returned from a deployment in “an Islamic country” to discover that his wife was transitioning and wanted a divorce (subject line “Regressivism stole my wife”); from a father terrified his daughter might attend Smith College; from fans who wanted to give him jokes to use about fat people, about gay people, about Muslims, about Hillary Clinton.

He also heard, with frequency, from accomplished people in predominantly liberal industries — entertainment, tech, academia, fashion, and media — who resented what they felt was a censorious coastal cultural orthodoxy. Taken together, they represent something like a network of sleeper James Damores, vexed but silent for fear of losing their jobs or friends, kvetching to Yiannopoulos as a pressure valve. For Yiannopoulos, these emails weren’t just validation, though they were obviously that. They sometimes became more ammunition for the culture war.

“I’m a relatively recent ex-lefty who received deep liberal indoctrination via elite private schools (Yale and Andover),” wrote one film editor who introduced herself as an “Undercover ‘pede in Hollywood.” (“Centipede” is slang for an online Trump supporter.) “I’ve been deeply closeted thus far due to the severe personal and professional repercussions of not beating the progressive drum.”

In an email titled “Working for E! Is Hell,” a production manager at the cable network wrote Yiannopoulos that her employer was a “contributor to the fake news machine and my colleagues have become insufferable. … I … offer you my services … a partner in fighting globalism.”

And Adam Grandmaison, whom Rolling Stone described as “underground hip-hop’s major tastemaker,” reached out to Yiannopoulos to suggest he investigate a journalist who had accused her ex-boyfriend of physical abuse.

In an email to BuzzFeed News, Grandmaison wrote that he was merely voicing concern about a black man being judged by the media, and that “I didn’t intend for [Milo] to write about it.” (Grandmaison’s email to Yiannopoulos began “first off i absolutely do not want credit for tipping you off to this.”)

Even more tips came in from tech workers.

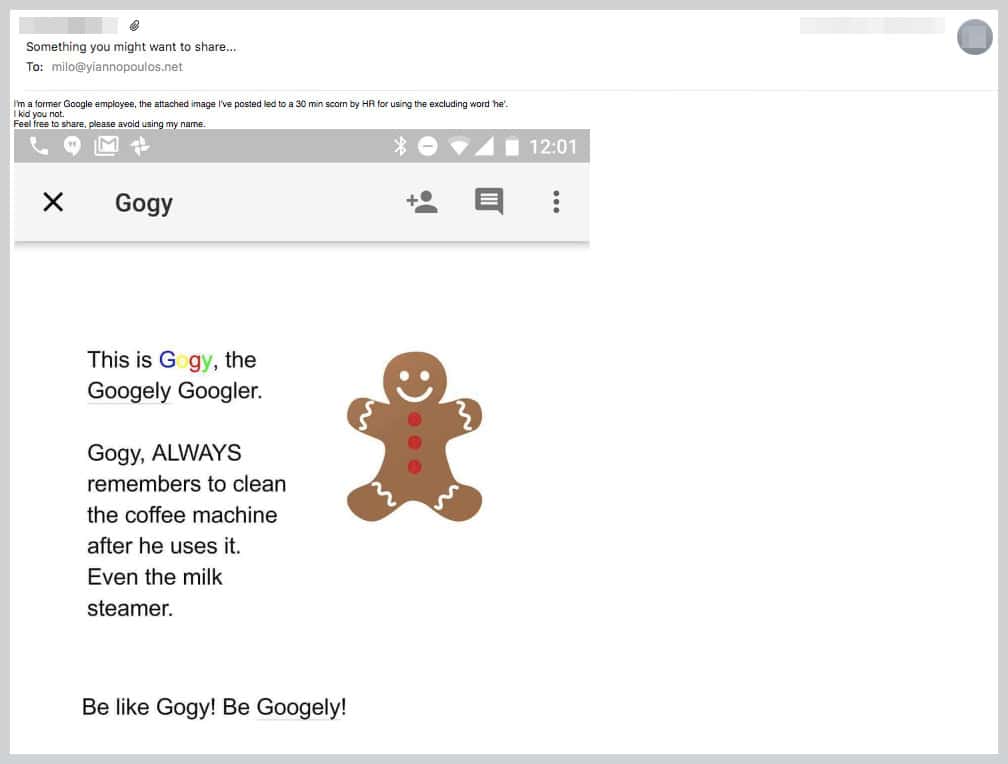

A Google employee sent Yiannopoulos a picture of a cartoon gingerbread man named “Gogy, the Googely Googler” that had been posted by a coffee machine to remind employees to tidy up. According to the Google employee, the sign had turned into an HR problem after employees were angered that Gogy was identified as male.

A Google spokesperson told BuzzFeed News the company has no record of Gogy or any related HR complaint.

A Twitter software engineer who felt betrayed by the “moral company” he had worked for since 2012, when it “stood for free speech,” emailed to tell Yiannopoulos that the removal of his verification in early 2016 “was obviously politically motivated.”

And some of these disgruntled tech workers reached beyond the rank and file. Vivek Wadhwa, a prominent entrepreneur and academic, reached out repeatedly to Yiannopoulos with stories of what he considered out-of-control political correctness. First it was about a boycott campaign against a Kickstarter with connections to GamerGate. (“These people are truly crazy and destructive. … What horrible people,” wrote Wadwha of the campaigners.) Then it was about Y-Combinator cofounder Paul Graham; Wadwha felt Graham was being unfairly targeted for an essay he wrote about gender inequality in tech.

“Political correctness has gone too far,” Wadhwa wrote. “The alternative is communism — not equality. And that is a failed system…” Yiannopoulos passed Wadhwa’s email to Bokhari, who promptly ghostwrote a story for Breitbart, “Social Justice Warrior Knives Out For Startup Guru Paul Graham.”

Wadwha told BuzzFeed News that he no longer supports Yiannopoulos.

“No gays rule doesn’t apply to Thiel apparently.”

Yiannopoulos also had a private relationship with the venture capitalist Peter Thiel, though he was more circumspect than some other correspondents. After turning down an appearance on Yiannopoulos’s podcast in May 2016 (Thiel: “Let’s just get coffee and take things from there”), Thiel invited the Breitbart tech editor for dinner at his Hollywood Hills home in June, a dinner Yiannopoulos boasted of the same night to Bannon: “You two should meet. … An obvious candidate for movie financing if we got external. … He has fucked [Gawker Media founder Nick] Denton & Gawker so many ways it brought a tear to my eye.” They made plans to meet during the July Republican National Convention. But much of Yiannopoulos’s knowledge of Thiel seemed to come secondhand from other right-wing activists, as well as Curtis Yarvin, the blogger who advocates the return of feudalism. In an email exchange shortly after the election, Yarvin told Yiannopoulos that he had been “coaching Thiel.”

“Peter needs guidance on politics for sure,” Yiannopoulos responded.

“Less than you might think!” Yarvin wrote back. “I watched the election at his house, I think my hangover lasted into Tuesday. He’s fully enlightened, just plays it very carefully.”

And Yiannopoulos vented privately after Thiel spoke at the RNC — an opportunity the younger man had craved. “No gays rule doesn’t apply to Thiel apparently,” he wrote to a prominent Republican operative in July 2016.

Thiel declined to comment for the story.

In addition to tech and entertainment, Yiannopoulos had hidden helpers in the liberal media against which he and Bannon fought so uncompromisingly. A long-running email group devoted to mocking stories about the social justice internet included, predictably, Yiannopoulos’s friend Ann Coulter, but also Mitchell Sunderland, a senior staff writer at Broadly, Vice’s women’s channel. According to its “About” page, Broadly “is devoted to representing the multiplicity of women’s experiences. … we provide a sustained focus on the issues that matter most to women.”

“Please mock this fat feminist,” Sunderland wrote to Yiannopoulos in May 2016, along with a link to an article by the New York Times columnist Lindy West, who frequently writes about fat acceptance. And while Sunderland was Broadly’s managing editor, he sent a Broadly video about the Satanic Temple and abortion rights to Tim Gionet with instructions to “do whatever with this on Breitbart. It’s insane.” The next day, Breitbart published an article titled “‘Satanic Temple’ Joins Planned Parenthood in Pro-Abortion Crusade.”

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, a Vice spokesperson wrote, “We are shocked and disappointed by this highly inappropriate and unprofessional conduct. We just learned about this and have begun a formal review into the matter.”

(A day after this story was published, Vice fired Mitchell Sunderland, according to a company spokesperson.)

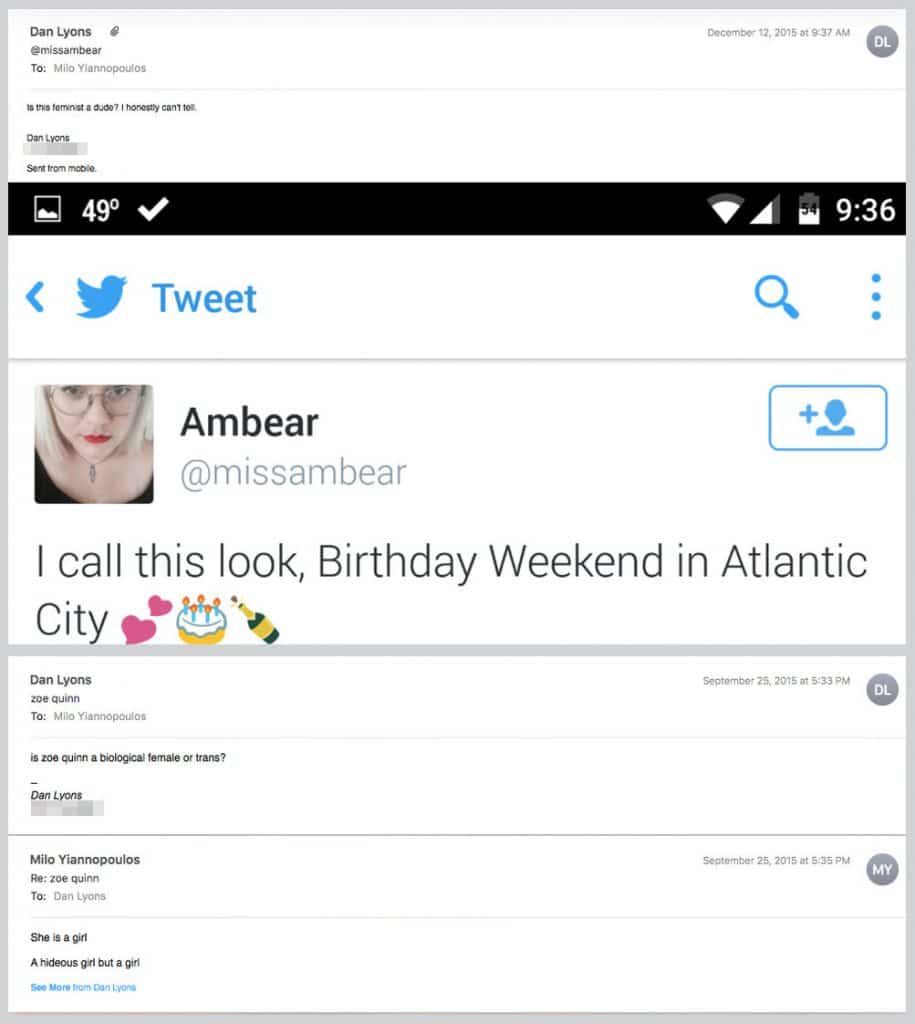

Dan Lyons, the veteran tech reporter and editor who also worked for nearly two years on HBO’s Silicon Valley, emailed Dan Lyons Yiannopoulos (“you little troublemaker”) periodically to wonder about the birth sex of Zoë Quinn, another GamerGate target, and Amber Discko, the founder of the feminist website Femsplain, and to suggest a story about the public treatment of the venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale, who had been accused of sexual assault in a lawsuit that the plaintiff eventually dropped.

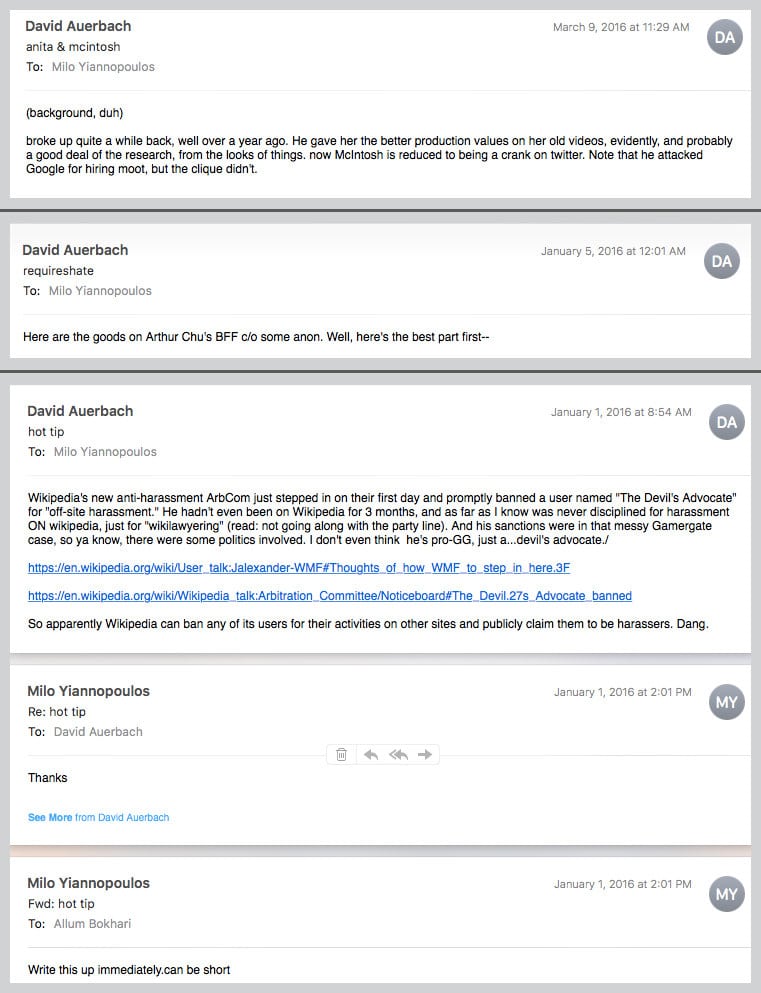

And the former Slate technology writer David Auerbach, who once began a column “Gamergate must end as soon as possible,” passed along on background information about the love life of Anita Sarkeesian, the GamerGate target; “the goods” about an allegedly racist friend of Arthur Chu, the Jeopardy champion and frequent advocate of social justice causes; and a “hot tip” about harsh anti-harassment tactics implemented by Wikipedia. Bokhari followed up with an article: “Wikipedia Can Now Ban You For What You Do On Other Websites.”

Reached by BuzzFeed News at the same email address, Auerbach said the suggestion that he had written the emails was “untrue.”

Meanwhile, a group of conservative thinkers associated with a variety of institutions — perhaps seeing in the Cambridge-educated, loquacious Yiannopoulos the ghosts of conservative public intellectuals past — struck up close correspondences with the young agitator. Rachel Fulton Brown, a University of Chicago medievalist, sent Yiannopoulos dozens of emails about the history of Christianity, the Crusades, and the righteousness of the West. When Brown posted a defense of Yiannopoulos on the university’s website, Breitbart wrote it up. Scott Walter, president of the conservative think tank the Capital Research Center, advised Yiannopoulos frequently on Republican politics and Catholicism. Yiannopoulos recommended one of his young assistants to Walter for a research project. And Ghaffar Hussain, who had previously worked at the controversial counterextremism organization Quilliam, sent Yiannopoulos news that a lecturer at a British university had spoken ambivalently of female genital mutilation. The note immediately led to a story on Breitbart.

From this motley chorus of suburban parents, journalists, tech leaders, and conservative intellectuals, Yiannopoulos’s function within Breitbart and his value to Bannon becomes clear. He was a powerful magnet, able to attract the cultural resentment of an enormously diverse coalition and process it into an urgent narrative about the way liberals imperiled America. It was no wonder Bannon wanted to groom Yiannopoulos for media infamy: The bigger the magnet got, the more ammunition it attracted.

But Yiannopoulos had also drawn others into the machine, others to whom a message about Western culture under threat meant much darker things.

For nearly a decade, Devin Saucier has been establishing himself as one of the bright young things in American white nationalism. In 2008, while at Vanderbilt University, Saucierfounded a chapter of the defunct white nationalist student group Youth for Western Civilization, which counts among its alumni the white nationalist leader Matthew Heimbach. Richard Spencer called him a friend. He is associated with the Wolves of Vinland, a Virginia neo-pagan group that one reporter described as a “white power wolf cult,” one member of which pleaded guilty to setting fire to a historic black church. For the past several years, according to an observer of far-right movements, Saucier has worked as an assistant to Jared Taylor, possibly the most prominent white nationalist in America. According to emails obtained by BuzzFeed News, he edits and writes for Taylor’s magazine, American Renaissance, under a pseudonym.

In an October 2016 email, Milo Yiannopoulos described the 28-year-old Saucier as “my best friend.”

Yiannopoulos may have been exaggerating: He was asking his acquaintance the novelist Bret Easton Ellis for a signed copy of American Psycho as a gift for Saucier. But there’s no question the men were close. After a March 2016 dinner together in Georgetown, they kept up a steady correspondence, thrilling over Brexit, approvingly sharing headlines about a Finnish far-right group called “Soldiers of Odin,” and making plans to attend Wagner’s Ring Cycle at the Kennedy Center.

Saucier — who did not respond to numerous requests for comment — clearly illustrates the direct connection between open white nationalists and their fellow travelers at Breitbart. By spring 2016, Yiannopoulos had begun to use him as a sounding board, intellectual guide, and editor. On May 1, Yiannopoulos emailed Saucier asking for readings related to class-based affirmative action; Saucier responded with a half dozen links on the subject, which American Renaissance often covers. On May 3, Saucier sent Yiannopoulos an email titled “Article idea”: “How trolls could win the general for Trump.” Yiannopoulos forwarded the email to Bokhari and wrote, “Drop what you’re doing and draft this for me.” An article under Yiannopoulos’s byline appeared the next day. Also in early May, Saucier advised Yiannopoulos and put him in touch with a source for a story about the alt-right’s obsession with Taylor Swift.

Saucier also seems to have had enough clout with Yiannopoulos to get him to kill a story. On May 9, the Breitbart tech editor sent Saucier a full draft of the class-based affirmative action story. “This really isn’t good,” Saucier wrote back, along with a complex explanation of how “true class-based affirmative action” would cause “black enrollment at all decent colleges” to be “decimated.” The next day, Yiannopoulos wrote back, “I feel suitably admonished,” with another draft. In response, after speculating that Yiannopoulos was trying to “soft pedal” racial differences in intelligence, Saucier wrote, “I would honestly spike this piece.” The story never ran.

At other times, though, Yiannopoulos’s writing delighted the young white nationalist. On June 20, Yiannopoulos sent Saucier a link to his story “Milo On Why Britain Should Leave The EU — To Stop Muslim Immigration.” “Nice work,” Saucier responded. “I especially like the references to European identity and the Western greats.” On June 25, Yiannopoulos sent Saucier a copy of an analysis, “Brexit: Why The Globalists Lost.”

“Subtle truth bomb,” Saucier responded via email to the sentence “Britain, like Israel and other high-IQ, high-skilled economies, will thrive on its own.” (IQ differences among races are a fixation of American Renaissance.)

“I’m easing everyone in gently,” Yiannopoulos responded.

“Probably beats my ‘bite the pillow, I’m going in dry’ strategy,” Saucier wrote back.

On occasion Yiannopoulos didn’t ease his masters at Breitbart in gently enough. Frequently, Alex Marlow’s job editing him came down to rejecting anti-Semitic and racist ideas and jokes. In April 2016, Yiannopoulos tried to secure approval for the neo-Nazi hacker “Weev” Auernheimer, the system administrator for the Daily Stormer, to appear on his podcast.

“Great provocative guest,” Yiannopoulos wrote. “He’s one of the funniest, smartest and most interesting people I know. … Very on brand for me.”

“Please don’t forward chains like that showing the sausage being made.”

“Gotta think about it,” Marlow wrote back. “He’s a legit racist. … This is a major strategic decision for this company and as of now I’m leaning against it.” (Weev never appeared on the podcast.)

Editing a September 2016 Yiannopoulos speech, Marlow approved a joke about “shekels” but added that “you can’t even flirt with OKing gas chamber tweets,” asking for such a line to be removed. Marlow held a story about Twitter banning a prominent — frequently anti-Semitic and anti-black — alt-right account, “Ricky Vaughn.” And in August 2016, Bokhari sent Marlow a draft of a story titled “The Alt Right Isn’t White Supremacist, It’s Western Supremacist,” which Marlow held, explaining, “I don’t want to even flirt with okay-ing Nazi memes.”

“We have found his limit,” Yiannopoulos wrote back.

Indeed, a major part of Yiannopoulos’s role within Breitbart was aggressively testing limits around racial and anti-Semitic discourse. As far as this went, his opaque organization-with-an-organization structure and crowdsourced ideation and writing processes served Breitbart’s purposes perfectly: They offered upper management a veil of plausible deniability — as long as no one saw the emails BuzzFeed News obtained. In August 2016, a Yiannopoulos staffer sent a “Milo” story by Bokhari directly to Bannon and Marlow for approval.

“Please don’t forward chains like that showing the sausage being made,” Yiannopoulos wrote back. “Everyone knows; but they don’t have to be reminded every time.”

By Yiannopoulos’s own admission, maintaining a sufficiently believable distance from overt racists and white nationalists was crucial to the machine he had helped Bannon build. As his profile rose, he attracted hordes of blazingly racist social media followers — the kind of people who harassed the black Ghostbusters actress Leslie Jones so severely on Twitter that the platform banned Yiannopoulos for encouraging them.

“Protip on handling the endless tide of 1488 scum,” Curtis Yarvin, the neoreactionary thinker, wrote to Yiannopoulos in November 2015. (“1488” is a ubiquitous white supremacist slogan; “88” stands for “Heil Hitler.”) “Deal with them the way some perfectly tailored high-communist NYT reporter handles a herd of greasy anarchist hippies. Patronizing contempt. Your heart is in the right place, young lady, now get a shower and shave those pits. The liberal doesn’t purge the communist because he hates communism, he purges the communist because the communist is a public embarrassment to him. … It’s not that he sees enemies to the left, just that he sees losers to the left, and losers rub off.”

“I need to stay, if not clean, then clean enough.”

“Thanks re 1488,” Yiannopoulos responded. “I have been struggling with this. I need to stay, if not clean, then clean enough.”

He had help staying clean. It came in the form of a media relations apparatus that issued immediate and vehement threats of legal action against outlets that described Yiannopoulos as a racist or a white nationalist.

“Milo is NOT a white nationalist, nor a member of the alt right,” Jenny Kefauver, a senior account executive at CapitalHQ, Breitbart’s press shop, wrote to the Seattle CBS affiliate after a story following the shooting of an anti-Trump protester at a Yiannopoulos speech. “Milo has always denounced them and you offer no proof that he is associated with them. Please issue a correction before we explore additional options to correct this error immediately.”

Over 2016 and early 2017, CapitalHQ, and often Yiannopoulos personally, issued such demands against the Los Angeles Times, The Forward, Business Insider, Glamour, Fusion, USA Today, the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post, and CNN. The resulting retractions or corrections — or refusals — even spawned a new category of Breitbart story.

Of course, it’s unlikely that any of these journalists or editors could have known about Yiannopoulos’s relationship with Saucier, about his attempts to defend gas chamber jokes in Breitbart, or about how he tried to put Weev on his podcast.

Nor could they have known about the night of April 2, 2016, which Yiannopoulos spent at the One Nostalgia Tavern in Dallas, belting out a karaoke rendition of “America the Beautiful” in front of a crowd of “sieg heil”-ing admirers, including Richard Spencer.

Saucier can be seen in the video filming the performance. The same night, he and Spencer did a duet of Duran Duran’s “A View to a Kill” in front of a beaming Yiannopoulos.

And there was no way the journalists threatened with lawsuits for calling Yiannopoulos a racist could have known about his passwords.

In an April 6 email, Allum Bokhari mentioned having had access to an account of Yiannopoulos’s with “a password that began with the word Kristall.” Kristallnacht, an infamous 1938 riot against German Jews carried out by the SA — the paramilitary organization that helped Hitler rise to power — is sometimes considered the beginning of the Holocaust. In a June 2016 email to an assistant, Yiannopoulos shared the password to his email, which began “LongKnives1290.” The Night of the Long Knives was the Nazi purge of the leadership of the SA. The purge famously included Ernst Röhm, the SA’s gay leader. 1290 is the year King Edward I expelled the Jews from England.

Early in the morning of August 17, 2016, as news began to break that Steve Bannon would leave Breitbart to run the Trump campaign, Milo Yiannopoulos emailed the man who had turned him into a star.

“Congrats chief,” he wrote.

“u mean ‘condolences,’” Bannon wrote back.

“I admire your sense of duty (seriously).”

“u get it.”

In the month after the convention, Yiannopoulos and Bannon continued to work closely. Bannon and Marlow encouraged a barrage of stories about Yiannopoulos’s late July ban from Twitter. Bannon and Yiannopoulos worked to distance themselves from Charles Johnson’splans to sue Twitter. (“Charles is PR poison,” Yiannopoulos wrote. “Charles is well intentioned–but he is wack,” Bannon responded.) And the two went back and forth over how hard to hit Paul Ryan in an August story defending the alt-right. (“Only the headline mocks him correct,” Bannon wrote. “We never actually say he is a cuck in the body of the piece?”)

But once Bannon left Breitbart, his email correspondence with Yiannopoulos dried up, with a few exceptions. On August 25, after Hillary Clinton’s alt-right speech, Yiannopoulos emailed Bannon, “I’ve never laughed so hard.”

“Dude: we r inside her fucking head,” Bannon wrote back.

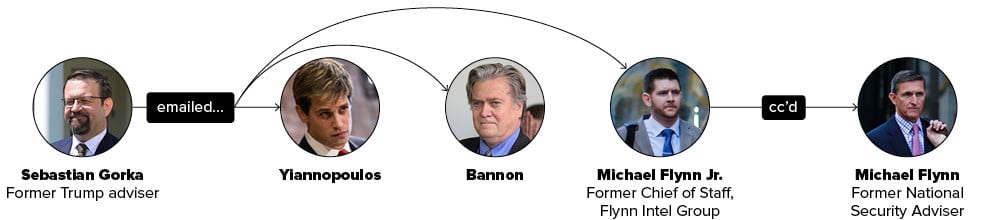

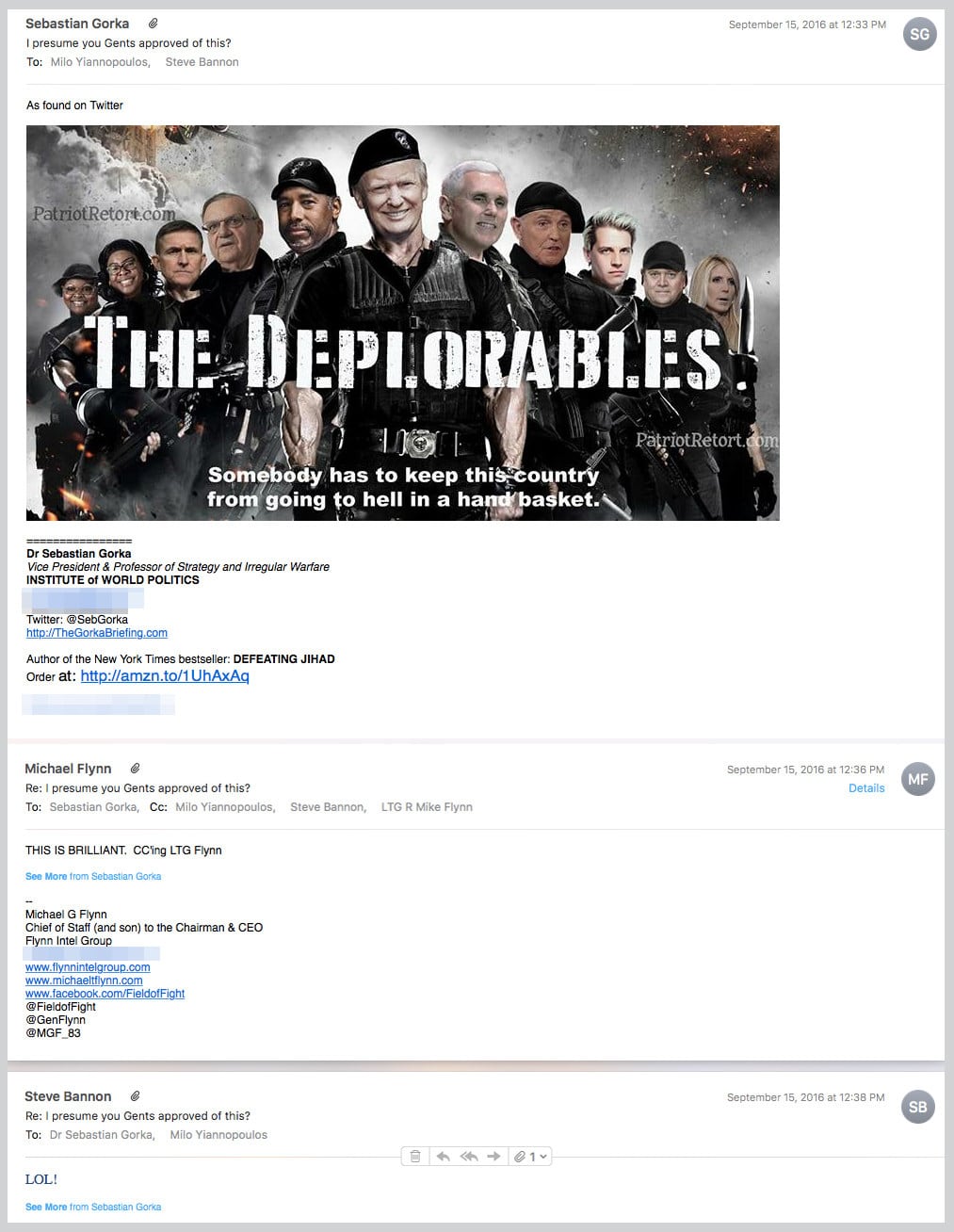

And on September 15, Sebastian Gorka, then an adviser to the Trump campaign, sent Yiannopoulos, Bannon, and Michael Flynn Jr., the son of Trump’s future national security adviser, a meme “as found on Twitter.” Watermarked by a conservative satire site called the Patriot Retort, the image was titled “The Deplorables,” and had superimposed various TrumpWorld faces on top of the all-star action movie heroes of the 2010 Sylvester Stallone vehicle The Expendables.

“I presume you Gents approved of this,” Gorka wrote.

“THIS IS BRILLIANT. CC’ing LTG Flynn,” Flynn, Jr. wrote back, referring to his father.

“LOL!” Bannon responded.

“Yes. I’m jealous!!” Gorka replied.

Still, as the campaign progressed into the fall, there were clues that Bannon continued to run aspects of Breitbart and guide the career of his burgeoning alt-right star. On September 1, Bannon forwarded Yiannopoulos a story about a new Rutgers speech code; Yiannopoulos forwarded it to Bokhari and asked for a story. On the 3rd, Bannon emailed to tell Yiannopoulos he was “trying to set up DJT interview.” (The interview with Trump never happened.) And on September 11, Bannon introduced Yiannopoulos over email to the digital strategist and Trump supporter Oz Sultan and instructed the men to meet.

Trump “used phrases extremely close to what I say — Bannon is feeding him.”

There were also signs that Bannon was using his proximity to the Republican nominee to promote the culture war pet causes that he and Yiannopoulos shared. On October 13, Saucier emailed Yiannopoulos a tweet from the white nationalist leader Nathan Damigo, who went on to punch a woman in the face at a Berkeley rally in April of this year and led marchers in Charlottesville: “@realDonaldTrump just said he would protect free speech on college campus.”

“He used phrases extremely close to what I say — Bannon is feeding him,” Yiannopoulos responded.

Yet, by the early days of the Trump presidency — and as the harder and more explicitly bigoted elements within the alt-right fought to reclaim the term — Bannon had clearly established a formal distance from Yiannopoulos. On February 14, Yiannopoulos, who months earlier had worked hand in glove with Bannon, asked their mutual PR rep for help reaching him. “Here’s the book manuscript, to be kept confidential of course… still hoping for a Bannon or Don Jr or Ivanka endorsement!”

The next week, video appeared in which Yiannopoulos appeared to condone pedophilia. He resigned from Breitbart under pressure two days later, but not before his attorney beseeched Solov and Marlow to keep him.

“We implore you not to discard this rising star over a 13 month old video that we all know does not reflect his true views,” the lawyer wrote.

Bannon, ensconced in the chaotic Trump White House, didn’t comment, nor did he reach out to Yiannopoulos on his main email. But the machine wasn’t broken, just running quietly. And it wouldn’t jettison such a valuable component altogether, even after seeming to endorse pedophilia.

After firing Yiannopoulos, Marlow accompanied him to the Mercers’ Palm Beach home to discuss a new venture: MILO INC. On February 27, not quite two weeks after the scandal erupted, Yiannopoulos received an email from a woman who described herself as “Robert Mercer’s accountant.” “We will be sending a wire payment today,” she wrote. Later that day, in an email to the accountant and Robert Mercer, Yiannopoulos personally thanked his patron. And as Yiannopoulos prepared to publish his book, he stayed close enough to Rebekah Mercer to ask her by text for a recommendation when he needed a periodontist in New York.

Since Bannon left the White House, there have been signs that the two men may be collaborating again. On August 18, Yiannopoulos posted to Instagram a black-and-white photo of Bannon with the caption “Winter is Coming.” Though he ultimately didn’t show, Bannon was originally scheduled to speak at Yiannopoulos’s Free Speech Week at UC Berkeley. (The event, which was supposed to feature an all-star lineup of far-right personalities, was canceled last month, reportedly after the student group sponsoring it failed to fill out necessary paperwork.) And Yiannopoulos has told those close to him that he expects to be back at Breitbart soon.

Steve Bannon’s actions are often analyzed through the lens of his professed ideology, that of an anti-Islam, anti-immigrant, anti-“Globalist” crusader bent on destroying prevailing liberal ideas about immigration, diversity, and economics. To be sure, much of that comes through in the documents obtained by BuzzFeed News. The “Camp of the Saints” Bannon is there, demanding Yiannopoulos change “refugee” to “migrant” in a February 2016 story, speaking of the #war for the West.

Still, it is less often we think about Bannon simply as a media executive in charge of a private company. Any successful media executive produces content to expand audience size. The Breitbart alt-right machine, embodied by Milo Yiannopoulos, may read most clearly in this context. It was a brilliant audience expansion machine, financed by billionaires, designed to draw in people disgusted by some combination of identity politics, Muslim and Hispanic immigration, and the idea of Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama in the White House. And if expanding that audience meant involving white nationalists and neo-Nazis, their participation could always be laundered to hide their contributions.

Yiannopoulos’s brand is his ego. Yet his role within the media ecosystem — building an audience around identity politics in the era of news organizations relying on social media for growth — makes him far less unique than he might believe. More and more outlets are firing writers and dumping resources into video. Given that trend, and particularly after Charlottesville, when the alt-right has proved a troublesome audience to court, it’s possible that Yiannopoulos’s use to Bannon has dwindled.

Or perhaps it hasn’t. For Bannon, of course, Yiannopoulos’s future was always in video, in spectacle. 2017 has provided plenty of spectacles that have gotten great ratings. Before it imploded, Free Speech Week had the potential to be the latest.

And the two men know the value of making a scene. In June 2016, Yiannopoulos, with Bannon’s enthusiastic support, planned to lead a gay pride march through a “Muslim ghetto” in Stockholm. Though Breitbart would later cancel the event over security concerns — Yiannopoulos expressed concern in private repeatedly — the Breitbart tech editor was in joking good spirits on June 26 when he wrote to Bannon of a “killer plan.”

“If I die doing this I expect a blackout on Breitbart.com for AT LEAST this afternoon,” Yiannopoulos wrote.

A few hours later, Bannon responded.

“And miss all the traffic in condolences?”