In the summer of 2018, the Indian State of Kerala was hit by severe rains and flood–the heaviest in nearly a century. The deluge affected 5.4 million people in this southern Indian state with a population of 35 million. More than a million-people had to be evacuated from their homes. As a result of the heavy rain from May onwards, 491 people died during the summer. Many more people could have died from the torrential waters that rose to dangerous heights in August. But, the people of Kerala, led by their Left Democratic Front government, by mass organisations, and an attitude of collective, selfless work, fought back. They would not let Kerala drown.

In front of the metro rail station at Companyppady, Aluva, Ernakulam district. Credit: K Ravikumar/Deshabhimani.

A government of the Left and a population galvanised by the idea of solidarity tackles a natural calamity with all possible resources–every instrument of the state came into play on behalf of the people, who themselves drew upon their resources to care for each other. Even the active hostility of India’s central government–led by the far-right Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)–did not dampen the enthusiasm of the state government and of the people to reduce the scale of the disaster.

Our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Dossier no. 9 (October 2018) tells the story of the floods, but more sharply, of the struggle by the left-led government and by Kerala’s population to overcome the havoc wreaked by the marauding torrents. Orijit Sen has generously drawn the cover of this dossier. It depicts the fisher community, who put their boats and their bravery on the line to rescue as many people and animals as possible. Our dossier is dedicated to all the people 3.who set aside their own safety to ensure the safety of their fellow beings.

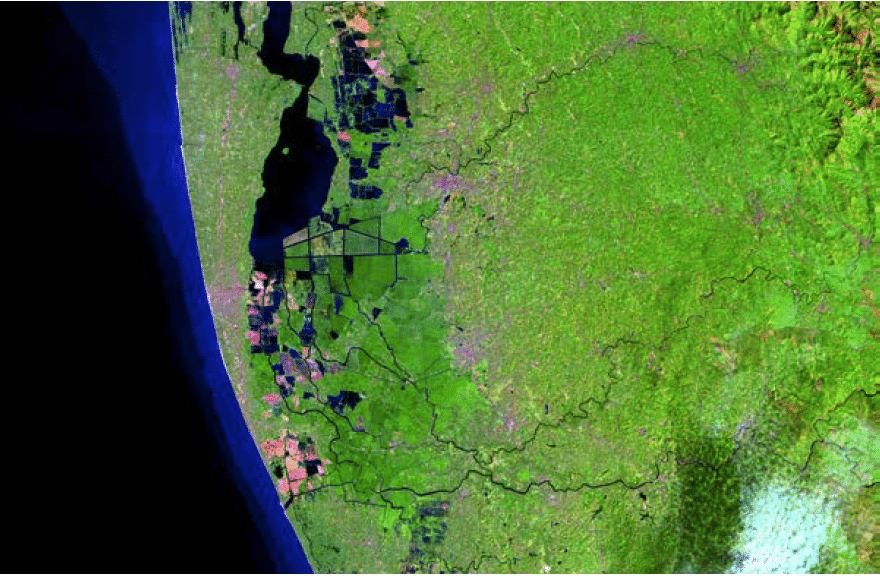

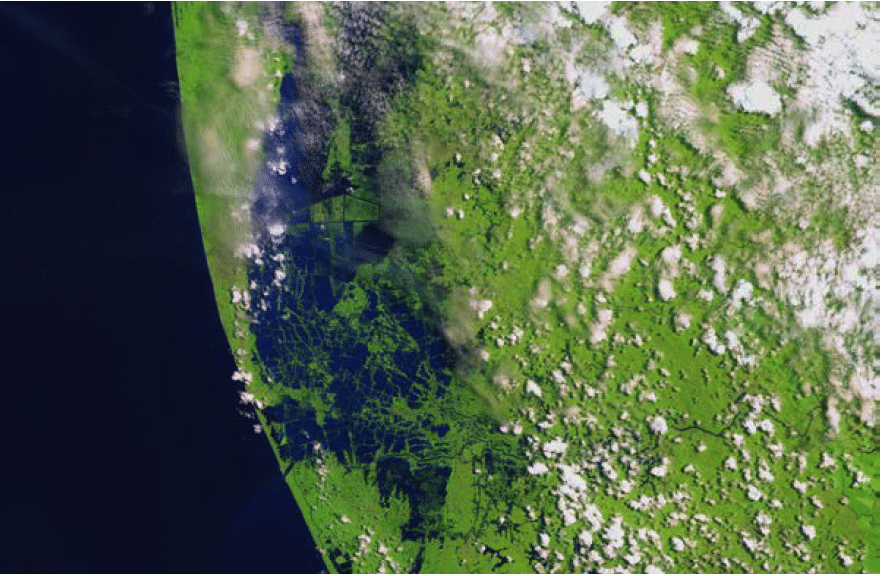

The coastal regions of south-central Kerala before and after the flood (a 6 month-period)

The rain

Even in normal years, Kerala receives an annual average of 2924.33 millimetres of rainfall, almost four times the annual average rainfall in the United States of America. Kerala’s total landmass is a mere 39,000 square kilometres, while that of the United States of America is 9,525,067 square kilometres.

This year, Kerala received much more rain in a very short period of time. The densest rainfall comes during the Monsoon season, which runs from June to September. From 1 June to 21 August, 2,387 mm of rain fell–41% higher than the normal rainfall. More dramatically, between 1 August and 19 August, 758.6mm of rain fell–164% higher than the norm. Even more dramatically, between 9 August and 15 August, Kerala received 257% excess rain. Nothing like this has been seen before. Idukki district, one of Kerala’s fourteen districts, was drenched by 679 mm of rainwater–447.6% higher than the normal rainfall. This was the worst hit district in the state.

As a result of this torrential downpour, massive flooding and landslides struck every district in the state. The state has 80 dams, of which 42 are large dams. As water levels rose alarmingly and as the dams threatened to overflow, the government had to release water in a controlled fashion.

Rescue and relief operations

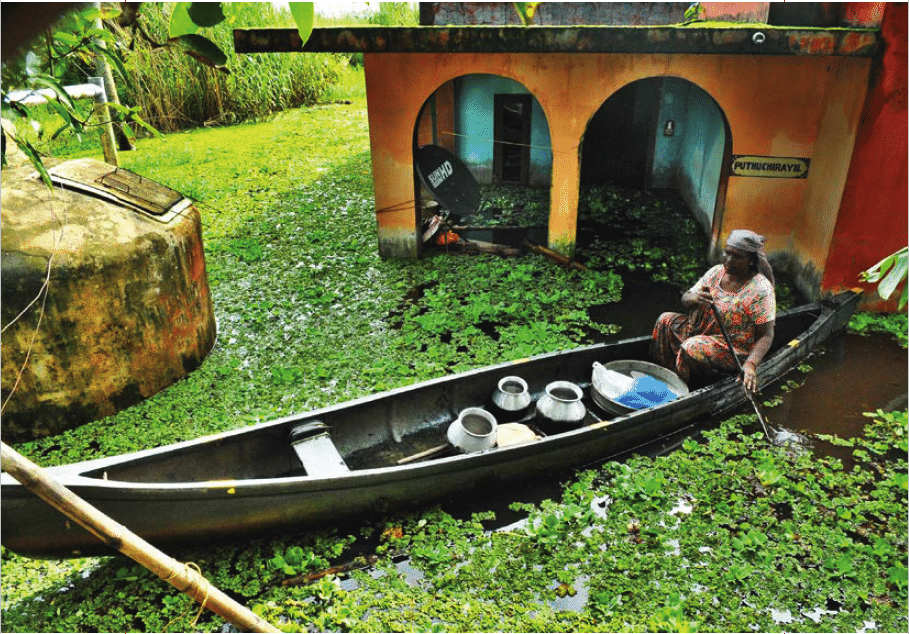

As flood waters inundated roads, homes and buildings in towns and villages across the State, people had to be evacuated in large numbers. Kerala has a high population density of 860 persons per square kilometre–more than double the national average–which compounded the gravity of the problem. People marooned in homes surrounded by water were rescued in mammoth rescue operations led by the State government, with the help of the central forces. In Kuttanad, a region in south-central Kerala which lies mostly below the sea level, about 250,000 people were evacuated in three days.

Relief camps were set up near the flood-affected areas. On 21 August, less than a week after the heaviest spell of rain, 1.45 million people had to take shelter in more than 3300 relief camps in the State. The numbers came down in the subsequent days as people began returning to their homes, most of which were damaged by the savage floods.

The rescue and relief mission has been widely hailed as one of the best in the history of such operations in India. The resoluteness and efficiency displayed by the Kerala government, led by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)], has come in for widespread praise.

The State government’s preparations to face the impending flood began in July. The people were alerted about the rising water levels in the dams, and those whose homes were certain to be submerged if dam waters were released were evacuated. Blockages downstream were cleared. The rains from August 8 onwards, however, surpassed all predictions of the India Meteorological Department.

The people of Kerala rose up to the occasion to confront the challenge head-on. The State government mobilised its entire machinery, with top civil servants, ministers and local governments having been entrusted with responsibilities by July. More than 40,000 police officers and 3,200 firefighters from across the state played a leading role in the rescue operations. However, the scale of the challenge was such that the generous help of the central forces were needed.

This is where the CPI(M)-led state government had to battle the intense cynicism and hostility of the BJP-led government at the centre. The number of armed forces and equipment that the central government sent to Kerala turned out to be much less than promised, and hence grossly inadequate. The State government asked for 5,000 soldiers, 100 helicopters and 650 motor boats for the rescue operations, but even by the morning of 18 August, at the peak of the rescue operations, the centre had allotted just 400 soldiers, 20 helicopters and 30 boats.

The ingenuity and power of the mass movements of Kerala came into the picture at this moment. Kerala is the State in India with the best human development indicators, and the left-wing mass organisations of Kerala and the communist-led governments they brought to power are credited with the State’s achievements in fields such as education and health. The ethos of self-reliance and mutual aid has been developed over decades, through literacy campaigns and through cooperatives, through local social organisations and through trade unions and peasant unions.

The very same mass organisations–student and youth organisations, trade unions and peasant unions–mobilised their members and supporters to organise relief missions. So did a large number of other political organisations and civil society organisations. Massive numbers of young people plunged into rescue work with all their might as volunteers in control rooms at 14 district administration headquarters and in flooded areas across the State.

Thousands of Keralites–both within Kerala and across the globe–used the internet and phone networks to collect information and GPS coordinates about people stranded in different places and passed on this information to the control rooms and rescue teams throughout the State. Several groups helped set up online databases using crowd-sourced databases. They augmented the Kerala government’s website keralarescue.in. For instance, the 40,000 member-strong Kerala Shaastra Saahitya Parishad (KSSP–the Kerala Science Literature Movement), which is India’s largest popular science movement, began its own website, unitekerala.com. Once the rescue efforts were completed, these websites were used to organise the collection and distribution of relief material.

The role played by the fishermen who joined the rescue mission with their fishing boats was crucial. Thousands of them, mostly from the southern districts, came into the flooded regions, with more than 4500 boats. Mobilised by trade unions and the State Government’s Fisheries Department, they waded into the waters even late at night, when everybody else had returned from the rescue operations. It is estimated that more than 70,000 people were rescued by fishermen. The State government undertook to repair their damaged boats, and instructed local governments to give them a grand welcome when they come home.

The State government itself organised a function to thank the fishermen on 29 August. The thousands who attended the programme broke into thunderous applause as the Chief Minister and others who spoke at the function saluted the fisherfolk and described their heroic services.

The relief effort has become an occasion where the camaraderie between people belonging to different religious communities in Kerala have come to the fore. Many Hindu temples, Christian churches, and Muslim mosques threw open their facilities to host people of all communities. They functioned as relief camps, and in many cases, made arrangements for people from other religious communities to hold worship. This is a counterpoint to the areas where the far-right BJP has cultivated religious hatred, pushing an anti-Muslim and anti-agenda deep into society.

An elderly woman being rescued from a flooded house at Companyppady, Aluva. Credit: K Ravikumar/Deshabhimani.

Kerala’s Chief Minister held daily press conferences during the peak days of the rescue operations, outlining the things that have been done already and the tasks that are to be carried out, along with giving essential instructions. The press conference became a much-awaited event during those days, being watched by hundreds of thousands of people on TV channels and on the Chief Minister’s Facebook page. Pinarayi Vijayan’s calm demeanour and the decisiveness with which he addressed concerns and questions contributed immensely to soothe the nerves of the people at a time when panic could have spread rapidly.

Large numbers of people die every year in India due to natural disasters, such as floods. The death toll in the floods would have been far bigger had it been not for the formidable efforts of the people and the government of Kerala. Although the cases are not strictly comparable, it might be worth noting that the floods in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand in the year 2013, which were triggered by less than half the amount of rainfall that Kerala witnessed this year, killed more than 5,700 people–more than ten times the figure in Kerala.

Hostility of the RSS-BJP

The rescue operation is only one part of the process. Relief and rehabilitation are another. The State government realised that it would need assistance to collect resources for the relief work and for the eventual rehabilitation of the people. The government requested that people from around the world contribute generously to the Chief Minister’s Distress Relief Fund. The mass organisations and the youth who were involved in rescue work enthusiastically got involved in running relief camps and in collecting, transporting and organising relief material.

While help began pouring in from across the globe, India’s far-right organisations–the BJP and its parent organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)–went on an extensive campaign to scuttle the relief efforts. If the far-right could hamper the Left Democratic Front government’s relief efforts, then it would be able to score political points–regardless of the human toll that such political callousness would require.

Not only did the BJP-led government in New Delhi refuse to send sufficient number of central forces for the rescue operations, it also has been reluctant to allot funds for relief and rebuilding. The centre has so far only sanctioned ₹6 billion as aid to Kerala, while the losses are estimated to be more than ₹250 billion.

As if the antagonism of the centre were not sufficient, the RSS-BJP actively propagated fake news to try and undermine the rescue and relief efforts of the State government and the people. One video circulated by the RSS’s social media handles involved a man in Army uniform claiming that Kerala’s Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan was not allowing the army to work in flood relief operations. Following this, the Army itself came out with a clarification, stating that the man in the video is an imposter spreading disinformation about the rescue and relief efforts.

The RSS-BJP also actively campaigned to discourage people from donating to the Chief Minister’s Distress Relief Fund. In a viral audio clip circulated by RSS networks, Suresh Kochattil, a member of the BJP’s IT cell, claimed that the flood-affected people in Kerala are rich. He sought to spread misinformation about fund utilisation from the Relief Fund, and asked people to donate to an organisation called ‘Sewa Bharati’ instead. Unsurprisingly, Sewa Bharati happens to be an RSS-affiliated organisation that is involved in spreading hatred, in religious-sectarian riots, and has even been accused of being entangled in a child trafficking scandal.

Post-flood rehabilitation

The people who returned to their homes from relief camps and the homes of friends and family saw their houses filled with debris and wreckage left behind by the deluge. In many cases, the houses suffered damages to their wiring, and even their structures. Other public and private buildings and facilities faced similar problems, especially that of muck that needed to be cleaned up.

Out of an estimated 371,203 flooded houses, 194,805 were already cleaned by 26 August, less than a week after the rescue operations were completed. Nearly 600 tonnes of waste had been removed from the worst-hit regions in seven districts by that time.

The challenge was particularly daunting in Kuttanad, which had the largest number of houses affected by flooding. A major rice-growing region with scenic backwaters, Kuttanad is spread over the Alappuzha and Kottayam districts. The rice fields and most houses lie below the sea level, as the region was reclaimed from lakes over centuries. The flood waters had destroyed the bunds (small dams) which protect the rice fields and houses from the lake waters. The bunds had to be rebuilt, water had to be pumped out and houses cleaned. The operation was of crucial importance to ensure that people could return to their homes and to prevent the outbreak of epidemics. It was a Herculean task.

A call for volunteers was issued on 24 August by Dr. TM Thomas Isaac, Kerala’s Finance Minister who is a legislator from Kuttanad. Huge pumps were brought in to pump out the water. About 60,000 volunteers–more than 10,000 from the CPI(M) alone–participated in the collective clean-up effort, named ‘Operation Rehabilitation’. Students, agricultural workers, carpenters, electricians, plumbers and volunteers from other political organisations and institutions joined in large numbers. They went from house to house, removing mud, cleaning up, using high-pressure pumps wherever necessary, and disinfecting the premises. Power and water connections were inspected and restored. Damaged doors and windows were repaired.

Mass organisations all across the State were involved in rehabilitation work. Ministers themselves were part of the work in many places to motivate more people to join in. Various civil society and political organisations pitched in with volunteers and resources. The left-wing Democratic Youth Federation of India (DYFI), with 5 million members in the State was also involved in the rescue and relief mission and deployed ‘Youth Brigades’ to clean up houses. The Kerala unit of the All-India Agricultural Workers Union and the State’s famous cooperatives, such as the Uralungal Labour Contract Cooperative Society (ULCCS), also contributed volunteers for the rehabilitation work.

Exemplary work was done by the Kudumbashree mission, a massive poverty eradication and women’s empowerment initiative started by the CPI(M)-led government in 1998. P. Sainath has said that it ‘could well be the greatest gender justice and poverty reduction programme in the world’. ‘Around 4,00,000 women of Kudumbashree self-mobilised across Kerala to do [post-flood] relief work, including collecting, packing and distributing relief material, cleaning up public spaces and private homes, and counselling affected families and putting them in touch with concerned authorities’, Brinda Karat, CPI(M) Polit Bureau member and former General Secretary of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) wrote in an article in The Hindu newspaper on 17 September. Kudumbashree groups cleaned up 11,300 public places including schools, hospitals, local government buildings and child care centres. 38,000 Kudumbashree members opened up their own homes to shelter families rendered homeless by floods. Kudumbashree members also contributed 74 million rupees to the Chief Minister’s Distress Relief Fund. ‘This scale of voluntary relief work by women is quite unprecedented by any standard’, Karat wrote.

Resource mobilisation

Rebuilding the flood-ravaged State would require enormous resources. The federal system of India is such that the bulk of the tax revenues collected from the States go to the central government. Various restrictions brought in by successive central governments during the neoliberal era have constrained the resource mobilisation capacity of the States. Furthermore, the centre has also imposed restrictions on the amount of money that the States are allowed to borrow from the market–a State government’s total borrowings cannot exceed 3 percent of the gross state domestic product. The refusal of the BJP-led central government to sanction sufficient amounts for relief and rehabilitation in Kerala becomes especially egregious in this context.

Flood level mark on black board, DD Sabha High School, Karimpadam, North Paravur. Credit: Navaneeth Krishnan S. By Edukeralam – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons.

The central government even put up roadblocks to prevent financial assistance from coming in from other countries. The government of the United Arab Emirates–a country with a large number of expatriate Keralites–offered a sum of ₹7 billion as aid to Kerala. But the central government refused permission for the amount to be transferred, citing unsubstantiated claims about ‘existing policy’ that allowed meeting requirements for relief and rehabilitation through domestic efforts alone. In fact, the decision, apparently driven by misplaced ‘national pride’, went contrary to existing central government policy. The National Disaster Management Plan cleared by the BJP government itself in 2015 says: ‘If the national government of another country voluntarily offers assistance as a goodwill gesture in solidarity with the disaster victims, the Central Government may accept the offer’.

Kerala’s resource mobilisation efforts have had to overcome such antagonism on the part of the central government. The State government has demanded that the borrowing limits be raised, and is exploring all possible options to mobilise resources from various channels, including raising taxes. People, including the large population of expatriate Keralites and the people of other States in India, have been contributing generously to the Chief Minister’s Fund. The State government has also floated a ‘salary challenge’ whereby people are encouraged to donate one month’s income to the Chief Minister’s Fund.

Woman transporting utensils from her flooded house at Kainakari panchayat, Kuttanad. Credit: Sivaprasad MA/Deshabhimani.

Towards a better, sustainable future

The post-flood reconstruction in Kerala has also been an occasion when serious debates and discussions on the future of development in the region are taking place.

Extraordinarily high rainfall such as this year’s has occurred before in Kerala. The heaviest rainfall in recent history was in 1924, which resulted in the ‘Great Flood of 99’ (in reference to the year 1099 in the Malayalam calendar). Another mighty deluge, the great flood of 1341 (Gregorian calendar), is believed to have resulted in colossal changes to the State’s geography. Muziris, the biggest port of the time is suspected to have been destroyed by the floods that year, and in turn, another port which took shape in Kochi rose to become the most important one.

But climate change has resulted in the frequency of extreme weather events that are increasing all over the world in the recent years. Kerala has to be prepared to confront such emergencies in the future as well, with better systems for forecasting natural disasters and for hazard mitigation.

Encroachments in flood plains and unscientific constructions have contributed to worsening the damage caused by floods in Kerala. There is more awareness today than ever before that reconstruction has to take place in a manner that will minimise such possibilities in the future. At the same time, the restoration of working people’s livelihoods has to be given prime importance as well. The living standards of people in Kerala are, on an average, better than those of other States in India, but they are still much below the living standards in developed countries. Material deprivation still exists on a substantial scale.

The challenge is to balance the need to improve the living conditions of people with the need to preserve the environment, in the context of the limited policy space and legislative powers available to a State government in India. There is recognition of the need for more sustainable ways of constructing buildings, minimising damage to the environment, and for more social control over land use, housing, and extractive industries such as stone quarrying. Left leaders have been talking about nationalising quarrying in the hilly regions, something that was already part of the election manifesto of the Left Democratic Front (the ruling coalition in Kerala, led by the CPI(M)). Comprehensive plans are needed to protect the highlands, the midlands and the coastal regions. Discussions are also taking place regarding the need to adopt healthier practices for housing in the densely populated State.

The manner in which the people of Kerala have confronted the biggest natural disaster in 94 years, through the sheer strength of their unity, collective action and social organisation, is truly remarkable. Through democratic discussions and organised efforts driven by a vision that keeps in mind their own bestinterests, they hope to build a future that will preserve past gains and make further advances in a sustainable fashion. With a fraction of the resources, Kerala was able to far outweigh the success of other relief efforts because of years of community building and investment in everyday people and public infrastructure and services.

Kerala’s example suggests the kind of world we would like to live in–a world that places the needs of people before profit, of sustainable development before corporate profiteering, of a people-centred agenda before disaster capitalism.