Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

On 18 August, soldiers from the Kati barracks outside Bamako (Mali) left their posts, arrested president Ibrahim Boubacar Këita (IBK) and prime minister Boubou Cissé, and set up the National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP). In effect, these soldiers conducted a coup d’état. This is the third coup in Mali, after the military coups of 1968 and 2012. The colonels who conducted the coup–Malick Diaw, Ismaël Wagué, Assimi Goïta, Sadio Camara, and Modibo Koné–have said that they will relinquish power as soon as Mali has been able to organise a credible election. These are men who have worked closely with military forces from France to Russia, and unlike the coup leaders of 2012–headed by Captain Amadou Sanogo–they are sophisticated diplomats; they have already demonstrated their skill in manoeuvring the media.

Ibrahima Kebe of L’association politique Faso Kanu said, ‘IBK dug his grave with his own teeth’. A veteran politician, IBK came to power in 2013 when Mali had lost its sovereignty due to a French-led military intervention called Operation Serval. The French claimed that they intervened to protect Mali from an Islamist onslaught in the north of the country. But, in fact, the spur for Mali’s deterioration comes from a range of factors, not the least of which was the decision of France and the United States–through NATO–to destroy Libya in early 2011. The war on Libya destabilised the situation in Africa’s Sahel region, where countries–already weakened by economic turbulence and International Monetary Fund (IMF) pressure–now found themselves unable to fend off French and U.S. military interventions.

Mali won its independence in 1960 with great promise, as its first president–Modibo Keïta–led it with a socialist and pan-African stance; the Keïta years were marked by import-substitution economic policies and an honest administration that attempted to build public sector delivery of social goods. But the country was dependent on one crop (cotton) for more than half its GDP, it had little processing and industry, and it had almost no sources of energy (all the oil is imported, and the hydroelectric plants at Kayes and Sotuba are modest). Poor soil and lack of access to water in the northern part of Mali put pressure on agriculture; Mali’s distance from the sea makes it hard to take its agricultural products to the market. Further, the cotton subsidy regime in both Europe and the United States strike at the heart of Mali’s attempt to develop its already dismal economy. A coup in 1968–backed by the imperialists–removed Keïta (who died nine years later in prison); the new government with the uncanny name of the Military Committee for National Liberation, set aside the socialist and pan-African policies, persecuted trade unionists and communists, and delivered Mali back into the French orbit. The 1973 drought and the 1980 entry of the IMF set the country into a cycle of crises, which culminated in the March 1991 democratic upsurge. Those street protests–magnificent in their enthusiasm–led to the victory of the Alliance for Democracy in Mali (ADEMA) led by Alpha Oumar Konaré.

Konaré’s government inherited a criminal debt of over $3 billion. Sixty percent of Mali’s fiscal receipts went towards debt servicing. Salaries could not be paid; nothing could be done. Konaré, who began as a Marxist in his youth but came to office as a liberal, begged the U.S. for debt forgiveness, to no avail. The more Mali’s government went into debt, the less able was the government to hire an honest bureaucracy, and so the government slipped deep into corruption. This was acceptable to France and the U.S., since a corrupt government meant easier interlocutors for the transnational gold mining firms–such as Canada’s Barrick Gold and the UK’s Hummingbird Resources–to siphon off Mali’s gold reserves at low prices. Behind everything that happens in Mali is its gold reserves, the third largest in the world. A Reuters story that came out a day after the coup had the reassuring headline: Mali’s gold miners carry on digging despite coup.

Since its independence, Mali has struggled to integrate all its vast territory–twice the size of France. The Tuareg communities began a rebellion in the idurar n Ahaggar mountains in 1962 demanding autonomy and refusing to honour the borders that divide their lands between Algeria, Libya, Niger, and Mali. A century-long deterioration of the land around the desert, magnified by the droughts of 1968, 1974, 1980, and 1985, devastated their pastoral way of life, sending many Tuareg to seek their livelihood in the cities of Mali and in Libya’s military as well as its informal labour force. Peace agreements signed between Mali and the Tuareg rebels in 1991 and 2006 fell apart due to the weakness of Mali’s military (salaries for soldiers were held down due to IMF pressure) and due to the arrival in the area of various Islamist groups expelled from Algeria.

These Islamists–the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)–coalesced and took over northern Mali in 2012-13. These groups–notably AQIM–had become part of the trans-Sahara smuggling networks (cocaine, arms, humans), and raised revenue through kidnapping and protection rackets. The threat posed by these groups was used by France and the United States to garrison the Sahel countries from Mauritania to Chad. In May 2012, the French approved a plan to intervene in the region, which was hidden behind the fig leaf of UN Resolution 2085 of December 2012. The G5 Sahel agreement yoked the countries of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger into the security agenda of France and the United States. French troops entered the old colonial base at Tessalit (Mali), while the U.S. built the world’s largest drone base in Agadez (Niger). They built a wall across the Sahel–south of the Sahara–as Europe’s effective southern border, compromising the sovereignty of these African states.

Protests against Ibrahim Boubacar Këita’s re-election in March 2020 escalated with trade unions, political parties, and religious groups taking to the streets. Media attention focused on the charismatic Salafi preacher Mahmoud Dicko (sensationally called the ‘Malian Khomeini’); but Dicko represented only a part of the energy on the streets. On 5 June, these organisations–such as the Mouvement espoir Mali Koura and the Front pour de sauvegarde de la démocratie, along with Dicko’s association–called for a mass protest at Bamako’s Independence Square. They formed the Movement of 5 June–Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP), which continued to pressure IBK to resign. State violence (including 23 killed) did not stop the protests, which called not only for the removal of IBK, but also for the end of colonial interference and for a total transformation of Mali’s system. M5-RFP had planned a rally on Saturday, 22 August; the military coup took place on Tuesday, 18 August. But the energy of the streets has not dissipated, and the coup leaders know that.

France, the United States, the United Nations, the African Union, and the regional bloc (Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS) have condemned the coup and called–in one way or another–for a return to the status quo; this is unacceptable to the people. L’association politique Faso Kanu has proposed a three-year political transition driven by the new leaders produced by M5-RFP, with transitional bodies created outside the formal state structure to strengthen the country’s depleted sovereignty. ‘Only the street of the people’, they write, ‘will free the country’.

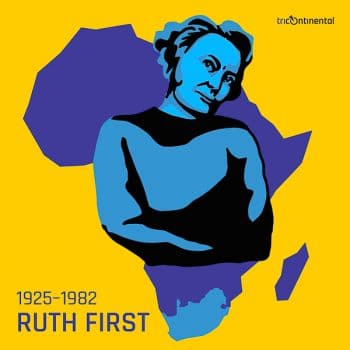

In 1970, the South African Marxist Ruth First–who was assassinated on 17 August 1982 by the apartheid regime–published Barrel of a Gun: Political Power in Africa and the Coup d’État. Looking at a variety of coups, including the 1968 coup in Mali, First argued that the military officers in post-colonial Africa had a range of political views, and many of them came to power to redeem the national liberation dreams of their people. ‘The facility of coup logistics and the audacity and arrogance of the coup makers’, First wrote, ‘are equalled by the inanity of their aims, at least as many choose to state them’. There is no indicator that the current coup leaders in Mali have such an orientation; regardless of their own character and their own external backers, they will have to face a population that is once more eager for a break from the colonial past and from the miseries of poverty.

In 1970, the South African Marxist Ruth First–who was assassinated on 17 August 1982 by the apartheid regime–published Barrel of a Gun: Political Power in Africa and the Coup d’État. Looking at a variety of coups, including the 1968 coup in Mali, First argued that the military officers in post-colonial Africa had a range of political views, and many of them came to power to redeem the national liberation dreams of their people. ‘The facility of coup logistics and the audacity and arrogance of the coup makers’, First wrote, ‘are equalled by the inanity of their aims, at least as many choose to state them’. There is no indicator that the current coup leaders in Mali have such an orientation; regardless of their own character and their own external backers, they will have to face a population that is once more eager for a break from the colonial past and from the miseries of poverty.

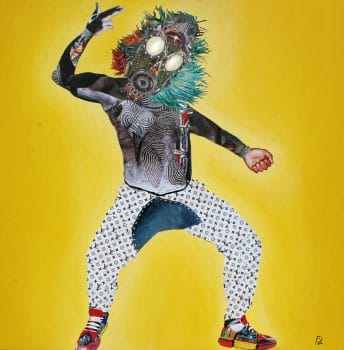

Imperialism marks the living history of the global south, as does the persistent resistance against it. Our third call for the Anti-Imperialist Poster Exhibitions is on the theme of ‘Imperialism’. The exhibition will be launched in conjunction with the International Week of Anti-Imperialist Struggle’s actions planned in October 2020. We invite you to share the call or to submit art to it.

Also please read the review of the Neoliberalism exhibition written by the curatorial collective of the Anti-Imperialist Poster Exhibition.

‘We paint because screaming is not enough and

neither crying nor rage is enough.

We paint because we believe in the people and

because we will conquer defeat’

(adapted from the poem, Why we sing, by Mario Benedetti).

Warmly, Vijay.